Searching for ATSC 3.0 at CES 2019

LAS VEGAS--As Yogi Berra might have observed about this year’s CES, “It was déjà vu all over again,” (at least with regard to the next-gen TV sets being displayed by both large and small manufacturers.)

Last year, with the ink still drying on the 3.0 standard and the FCC’s green-lighting of its use by the nation’s TV stations a couple of months earlier, ATSC, NAB and CTA industry officials gathered to celebrate its arrival with a champagne toast on the opening day of the CES. However, there was not a single 3.0-capable set to be found among the super-bright, super-big, super-colorful, super-intelligent, (and, in some cases, super-expensive) television receivers that literally reached the ceiling of the Los Vegas Convention Center which hosted the 2018 show.

Fast forward a year—has there been any change in the 3.0 situation?

In a word, no! If anything, there was less ATSC 3.0 presence this time, as one TV manufacturer did put up a sign in its 2018 CES display space that touted the benefits of the new DTV transmission standard. Not even the sign was there this time.

CRITICAL MASS

While most of the TV set exhibitors quizzed about the lack of ATSC 3.0 product (which has been available since 2017 in South Korea) were silent about its absence at CES, John Taylor, senior vice president of public affairs for LG USA did offer an explanation.

“You’re a year or so early,” he said. “We’re trying to time the introduction of the product with the critical mass of Next-Gen TV broadcasting, and the whole industry seems to be moving toward a 2020 product launch.” Taylor did seem fairly certain that the 3.0 sets would be populating manufacturers’ exhibit spaces at the 2020 CES to “prime the pumps” of buyers who would be at that show to decide what to stock their stores with for the 2020 holiday buying season.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

And while others in the industry have hinted that there may be a problem with delivery of some of the components needed for 3.0 sets, Taylor was quick to state otherwise.

“There’s no technology issue at all,” he said. “It’s a business marketplace consideration about the right time to introduce the product in the U.S. market. We could ship the product today. As you know, we’re shipping ATSC 3.0 TVs in Korea, but it has to make sense for the U.S. market and that’s heading towards 2020.”

Taylor noted that LG and its Zenith R&D subsidiary are providing receiver products and technical support for some of the U.S. ATSC 3.0 field trials.

THE VIEW FROM OVERSEAS

Peter Siebert, head of technology for the DVB (Digital Video Broadcast organization, a Swiss-based consortium that sets digital broadcast transmission standards for Europe, and is roughly the equivalent of the Advanced Television Systems Committee), was at the show and had a slightly more pessimistic view when asked about the appearance of ATSC 3.0 TVs at the 2020 edition of the “world’s biggest consumer electronics show.”

“I don’t think so,” said Siebert. “And the reason why I don’t think so is that there has to be a strong commitment from the broadcasting community to say ‘we will introduce the service,’ and personally from a European perspective, I don’t hear this message from the North American broadcasters.

“It’s a typical ‘chicken and egg’ problem and there must be somebody breaking it,” he continued. “The broadcasters must say ‘we offer a service.’ It doesn’t help that the industry develops products first. For example, when I look at the televisions, there are many 4K televisions on the market. However, this doesn’t mean that we have 4K broadcasts. I think the broadcaster has to make a firm commitment to introduce the service and then the receiver industry will follow.”

Siebert noted that when the United Kingdom decided to migrate from the original DVB-T (terrestrial broadcast) standard, which was struck in 1997, to an updated version, DVB-T2, which was completed in 2008, there was no “chicken and egg” situation because there was a clear commitment from the BBC for a rollout of the improved HD service via DVB-T2.

“It can go very fast if well planned,” he said, noting that the transition was accomplished in Ukraine in a single year and in two years in Germany. Siebert did admit that the move to DVB-T2 didn’t go quite so fast in every European nation, explaining that “typically, the more a country is relying on terrestrial television, the longer it takes, because you have a much bigger legacy of receivers that you have to update before you can start a new service.”

However, lack of suitable receivers didn’t seem to be an issue in the DVB-T2 transition.

“In Germany, when we went from DVB-T to DVB-T2, we had all stakeholders sitting together at a round table and making a plan on how to introduce T2,” said Siebert. “It was very clear. The broadcasters said on this date we will switch our transmissions to the new DVB-T2 specification. And it was also very clear that the consumer industry [would be] ready way before this, providing the necessary equipment. So, at the time the switchover happened, quite a high percentage of receiving equipment was ready. I think it is necessary that all stakeholders sit together, to agree on a plan and then stick to the plan.”

THE VIEW FROM SINCLAIR

Since ATSC 3.0’s inception, one of its biggest backers has been the Sinclair Broadcast Group, and for the past several years the broadcast station group has been at CES to promote the standard, even operating a transmitter on Black Mountain south of Las Vegas to provide TV set exhibitors with 3.0 signals to demonstrate reception of OTA UHD video at the show. Sinclair has also hosted demonstrations of 3.0 technologies a few blocks away from the convention halls in a suite at the Wynn Hotel.

Mark Aitken, Sinclair’s vice president of advanced technology, was on hand this year to offer his take on the absent ATSC 3.0 hardware.

“I think it’s very simple,” said Aitken. “There two issues. The difficult one is content protection, and this issue has not been answered. You’ve got a lot of dancing around on the part of the networks with respect to what their requirements are for content protection, and not a single solution that has been put on the table has been supported by all of the content providers—and I might add content distributors or MVPDs. So, you have a bit of a stalemate. For me, it’s a fairly easy one to resolve. I look at it and say as a starting point ‘if Widevine [DRM] is good enough for Netflix, why isn’t it good enough for broadcast?’

“The networks will always try to extract the broadcaster from out of the middle of the relationship with the consumer,” continued Aitken, noting that reluctance of networks and program providers to allow their content to be transmitted by affiliates deploying ATSC-M/H [aka Mobile DTV] was one of the reasons for that mobile initiative’s ultimate demise.

“I think there’s been a soft promise made on the part of broadcasters that we’re willing to come to a solution. There’s been an unwillingness on the part of the large content players to sit down and really try to solve that problem, at least with Sinclair. They have their own views and their views are not shared equally with all broadcasters. And so, for the very same reasons that we ended up with Dolby AC-4 as an abstraction of the Atmos production environment in Hollywood, the issue of content protection is being driven by those same Hollywood entities, which for a broadcaster is driven through the network.”

Aitken summed up the situation by stating: “It is a political problem, absolutely.”

Aitken said that Sinclair will light up 26 markets by the end of 2019.

“There’s a requirement by the FCC that there be some replication across ATSC 1.0 and ATSC 3.0,” he said. “There may have to be an opportunity to force that issue at a regulatory level, which nobody really wants. But at the end of the day sometimes you solve problems by spilling a little blood first.”

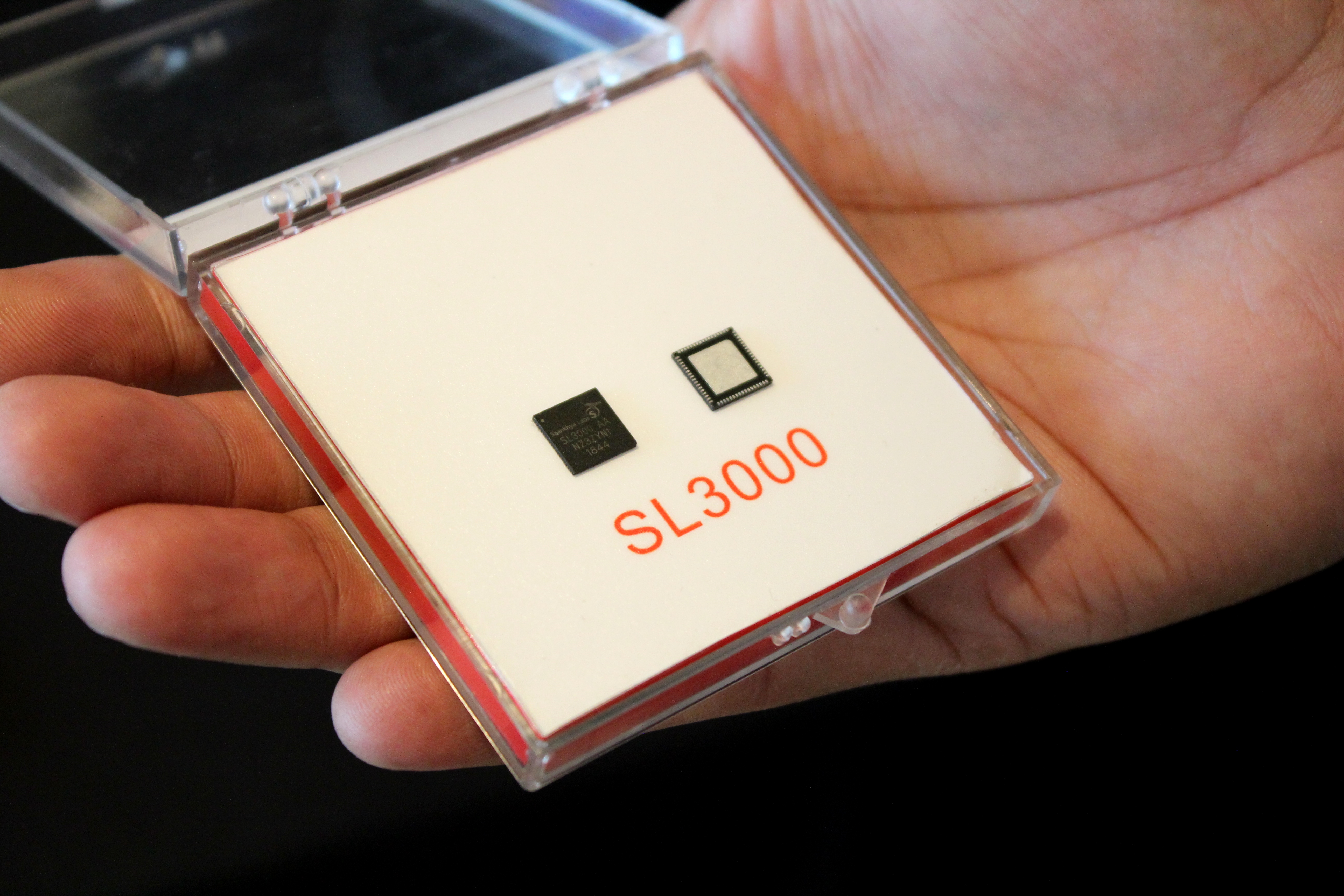

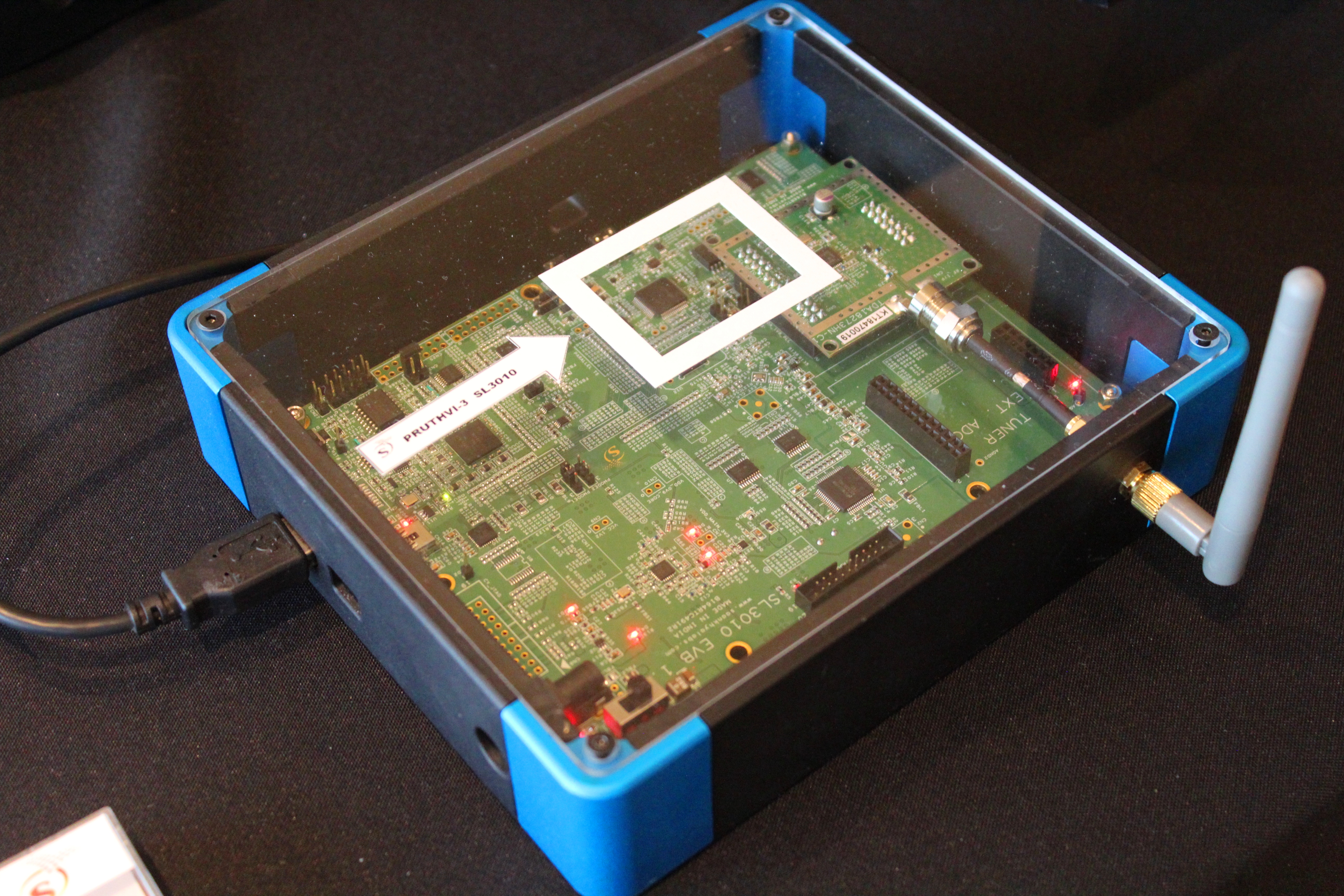

THE CHIP

Despite his disappointment with this stalemate in the rollout of 3.0, Aitken was in a celebratory mood as he announced the release of an integrated circuit specially designed and fabricated for Sinclair. The chip’s unveiling marked the end of a nearly two-year journey that began with a pledge to supply free ATSC 3.0 demodulator chipsets to any company manufacturing smartphones or other handheld viewing devices that would commit to including them in their products.

Explaining the genesis of the project, Aitken—who is a firm believer that broadcast television’s future lies in mobile devices—said that after surveying existing 3.0 chip products, he quickly came to the conclusion that none were really satisfactory for mobile device applications.

“We knew what sort of power the available chips consumed,” said Aitken. “It’s easy enough to guess the power requirement specs, because it’s almost like a curling iron if you’ve ever put your finger on one. If we were ever going to have a mobile-enabled device—something that was suitable for embedding in phones, something that could couple-up to a cellphone without draining the life out of the phone—we would have to create it.”

Frustrated that none of the large consumer electronics firms showed much interest in mobile TV products, he decided to go it alone.

“We went literally to the top of the ladder, and at the end of the day, they saw the world the way that they choose to see the world,” he said. “They saw no place for mobile ATSC; certainly not at this time.”

Aitken recalled an Indian company with a reputation for low-power consumption specialty integrated circuit design—Saankhya Labs—from his involvement with ATSC M/H—and contacted them.

“I decided to pick up the phone and have a conversation with Praag Naik, who is the president,” said Aitken. “We had a conversation, and it became evident that we shared a much higher-level understanding of what was possible, so Sinclair invested.”

The result was the creation of a very low-power consumption chip that can easily be incorporated within a mobile viewing device without substantially decreasing its battery life or increasing its physical profile.

NOT JUST FOR ATSC 3.0

Aitken said that as Saankhya had an established reputation in software-defined radio (SDR) technology, it was decided early on to create a chip that was signal agnostic, with software dictating which of a dozen or so digital TV signals it will decode, including ATSC 1.0 and the European DVB-T2 standard.

“We’re not building an ATSC 3 chip,” he said. “We’re building a chip that can go in set-top boxes, in televisions, in tablets, for any global broadcast standard, including digital radio. You level your risk by having a multistandard chip.”

Aitken says that at present about 1,000 of the chipsets have been created, and the foundry is ready to roll out millions more. Asked about takers for the free devices, he acknowledged that this has been a bit of a hard sell, but sees some light on the horizon.

“We’ve offered a major carrier five million chips. We’ve also offered the engineering of that chip into the device and we’ve offered the availability of the IP data stream, but that has not been enough to entice them to do that yet, but we are knee-deep into discussions with a USB manufacturer.”

Aitken views this as a first step to getting the chips into mobile devices, explaining that they would be part of a USB-C “dongle” equipped with an embedded antenna and designed to plug into mobile devices. And by the chip’s not being specific to ATSC 3.0, the dongle could be used virtually anywhere that digital over-the-air broadcasting is taking place.

“It would host DVB-T2, ISDB-T, ATSC 1, and other standards just by changing the software,” said Aitken. “It could be used in any part of the world.”

For a comprehensive list of TV Technology’s ATSC 3.0 coverage, see our ATSC3 silo.

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as editor-in-chief of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a Life Member of the IEEE and the SBE.