Future Is Near for Object-Based Broadcasting

The concept for object-based broadcasting has been around for more than 20 years, and the technology to deliver it is tantalizingly close. Chances are that you will see some form of it on your home TV in the next few years, and it will certainly be a factor for video you watch on mobile devices and computers.

The BBC performed this test using a variety of objects, including the presenter, subtitles, background map, weather/rain overlays, weather icons, day/time and calendar/reminder information. The size and location of the objects differs depending on the viewing device. Object-based broadcasting treats the on-screen and audio components as objects, delivering them as-needed/where-needed depending on the device used to view the broadcast. A simple example would be an onscreen “bug” identifying the broadcaster—it might be sized and positioned in one location on a big-screen TV, and sized and positioned differently for viewing on a cell phone.

“We see object-based broadcasting as a means of giving the consumer and broadcaster greater control over what’s rendered on the device,” said Nandhu Nandhakumar, Ph.D., senior vice president at the LG Technology Center of America. “The control can also be in the broadcaster’s hands, like with certain types of personalization, such as targeted ads. Other uses of object-based broadcasting can include interactivity, personalized graphic overlays, and alternate audio, video or caption tracks.”

PERSONALIZED AND TARGETED

LG is a major manufacturer of both in-home televisions and mobile devices, as well as an important player in the development of the nascent ATSC 3.0 standard. It has been involved in some early object-based broadcasts that were available on cable systems across the U.S.

“LG already has deployed TVs with interactive features where the data elements associated with interactivity are personalized and targeted,” Nandhakumar said. “The triggers for interactivity are extracted from the content, and based on the user profile shared with the interactive service, personalized data elements are delivered to specific users for rendering on the TV. Interactive services have been periodically available on a trial basis on various LG smart TV models for a few years—based on various business arrangements with program providers, such as Showtime, SyFy and Pearl TV.”

Object-based broadcasting was first fleshed out decades ago, with much initial development at the Massachussetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab. In the mid-1990s, V. Michael Bove, professor of media technology at MIT’s Media Lab, studied the available compression technology and determined that not all content was treated equally.

“Transform-based compression algorithms like JPEG and MPEG (and wavelet-based ones as well) are optimized for camera imagery at the expense of graphical patterns,” Bove said in a 1995 article in TV Technology. “In the case of motion-compensated coders and scrolling titles (or stationary text over a camera pan), the inefficiency is worsened by the lack of any notion of background and foreground: The encoder is spending its bit-budget constantly retransmitting information about occluded and revealed regions of the image.”

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Bove and his colleagues described what’s now called object-based broadcasting as a way to permit optimal image quality for both background and foreground items using the available coding, while consuming minimal additional bandwidth. MIT’s Media Lab went on to get patents on the technology, which were eventually sold to Tandberg Television and subsequently to Ericsson. Bove said that he’s not aware that Ericsson is using these patents.

BBC PIONEERING WORK

One broadcaster actively testing object-based broadcasting is the BBC. “The BBC has been using the term object-based broadcasting for a number of years,” said Matthew Brooks, senior BBC R&D engineer. “Generally, when we talk about object-based broadcasting, our objects are the assets we use to compose experiences for our audience, whether they are radio programs, television programs or interactive applications. These objects range from the familiar—video clips, audio clips, captions, stills—to the unfamiliar, like a data stream representing the speed of a racing car.

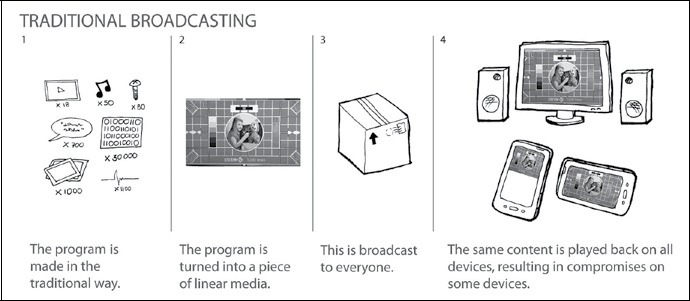

How a traditional broadcast is made today.

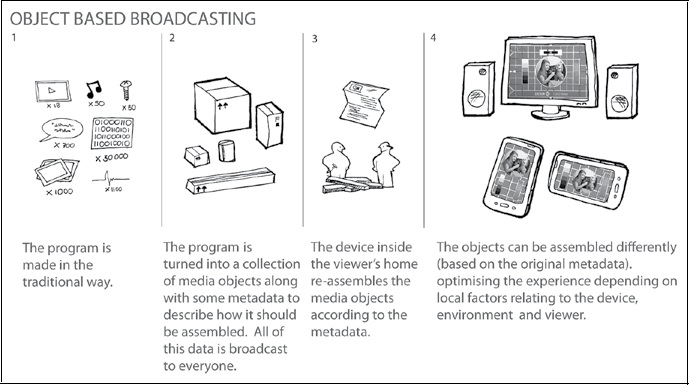

“In traditional broadcasting, we package up those objects before they get to the audience, and deliver a video to them,” Brooks said. “This is straightforward, but the content of the video is inflexible. “With object-based broadcasting, we deliver the individual objects to everyone, along with information describing the ways in which they can be reassembled. The audience’s devices can then use that information to reassemble the objects into a flexible experience.”

The combination of the internet, cellular mobile networks and smart TVs means that some form of object-based broadcasting can be done today, and the BBC has dipped its toes into these waters.

“Object-based broadcasting can be delivered over IP today—we delivered a variable-length radio program in this manner in 2015, and we’ve made a number of very different object-based prototypes, which we’re using to inform our work on a unified object-based broadcasting model,” Brooks said. “There’s a lot of work to do before we can achieve this technically, alongside building an understanding of what impact object-based broadcasting has for audiences and production teams.”

How an object-based broadcast could be created.

The BBC is also considering how to implement object-based techniques into its over-the-air television broadcasting. “There’s a couple of approaches we could take here,” Brooks said. “Firstly, we side-load some content over IP to augment the broadcast experience. This could either be done pre-broadcast, or in a just-in-time manner. Secondly, we can always render object-based experiences down to pre-tailored traditional broadcast experiences—useful for both over-the-air broadcasting, and delivering to ‘thin client’ devices that don’t have the processing power to assemble object-based experiences in real time.”

LG is already working on incorporating the transmission of various broadcast components (objects) into its viewing devices, and expects that ATSC 3.0 will be a good fit for hybrid OTA-IP presentations.

“In the case of ATSC 3.0, it’s designed as a hybrid broadcast/broadband system,” Nandhakumar said. “So a broadcaster could deliver main video, audio and caption tracks via broadcast, then deliver alternate components via broadband. The presence of the alternate components is signaled in the broadcast stream so that the receiving device can offer the alternates to the viewer. Targeted content insertion is another example of how broadcast and broadband can work together in ATSC 3.0. In this case, a ‘mainstream’ ad can be delivered in the broadcast and a targeted ad delivered via broadband can be spliced in for certain audiences.”

There’s much yet to do regarding object-based broadcasting, not the least of which is developing standards for consumer products on the receiving side that are compatible with the encoding done at the transmission end. However, the proliferation of smart TVs gives manufacturers an increasingly attractive way to combine both OTA and IP delivery right in front of the viewer.

The tools at the receiving end are becoming common. How long will it be before a way is hammered out to deliver content that leverages the strengths of both these delivery systems?

Bob Kovacs is the former Technology Editor for TV Tech and editor of Government Video. He is a long-time video engineer and writer, who now works as a video producer for a government agency. In 2020, Kovacs won several awards as the editor and co-producer of the short film "Rendezvous."