The Challenge of Bringing HDR to More Broadcasts

While single-camera production has been an early adopter, the demands of producing legacy formats side by side—and in real time—has made HDR slower to grow into multicamera work

Of all the new technologies offered to film and TV production in the last decade or two, HDR probably received the warmest immediate reception. While single-camera production has been an early adopter, the demands of producing legacy formats side by side—and in real time—has made HDR slower to grow into multicamera work.

Kevin Salvidge, Sales Engineering and Technical Marketing Manager at Leader/Phabrix referred to a recent EBU session on the subject, noting the complexities involved. “They are concerned that this is appearing too complicated, and that’s preventing HDR [from] becoming mainstream—the knowledge and the power is in the hands of a few people,” he said. “If you’ve got one of those people on your production, bingo, the world’s your oyster. If not, how do you do this?”

The answer, Salvidge goes on, will involve both new equipment and new techniques, but decisions made now are likely to be foundational. “We are currently defining the workflows for the next twenty years,” he said. “The workflows that now seem to be universally adopted are a single master production. The vision mixer is cutting UHD, wide color gamut HDR, so any sources that are not 4K, wide color gamut, high dynamic range are upconverted. That’s close to the workflow the BBC used for the coronation.”

Little Room for Error

As a supplier of test-and-measurement equipment, Phabrix might not ordinarily expect to be involved in that sort of signal processing. Salvidge describes a process of convergence: “The HDR supervisor is the only person who sees HDR Images, and is having to compare both of them. The camera will also output HDR and this is normally where a conversion product sits. And if you’ve got a production, let’s say the FIFA world cup final, with 42 cameras, that’s a lot of kit, a lot of potential to go wrong.”

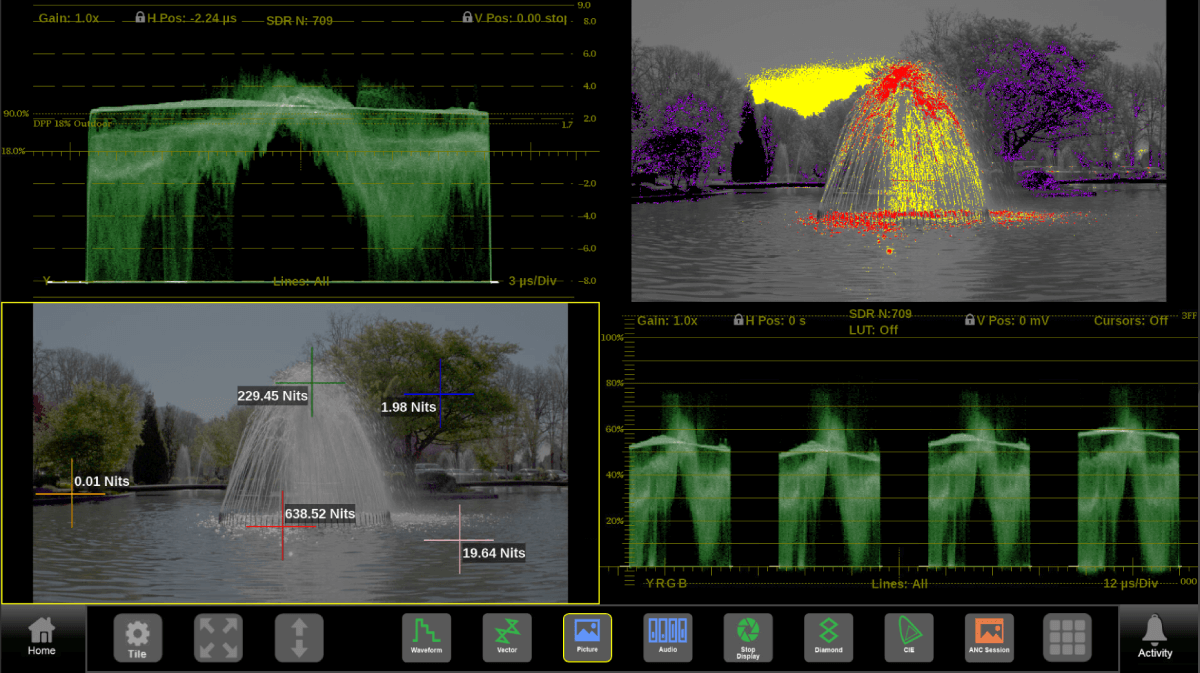

With Leader and Phabrix now under the same umbrella, some efficiencies have been realized, Salvidge adds. “What we’ve done with the Leader product is the ability for a LUT to be loaded into the waveform monitor, so now you remove that conversion product,” Salvidge says. “You switch on the LUT and you can see the picture, waveform, vectorscope, and the CIE color chart, and the beauty of that is the same LUT is being applied on the output of the truck as well.”

That kind of technical consolidation helps everyone, though Salvidge tells us that the concerns of vision engineering for HDR has also provoked some changes in tools, too.

“The Leader and Phabrix products, in the old days, used to display one analysis tool, or a quad split with four of them,” Salvidge says. “If you’re doing HDR, you need the picture, the waveform, the vector, the CIE chart, and you may be monitoring other parameters as well. You need to have more than four tools.

“So now you’ve got this customizable layout, on both products, which allows you to save it for a particular operation you’re doing,” he added. “We have a lot of freelance people who walk around with their setup on a flash key.”

There will, however, always be considerations which are creative, and harder to characterize on a test-and-measurement display, as Salvidge points out. “They’ve changed the way they shoot. Originally they’d focus on, say, a skier. You have very skilled camera operators, three or 4 km away. They’ll pick up a stick man doing almost 100 kph and they’d have a fairly wide shot. The guys who did the HDR testing said 90% of the screen was white, but you now see them frame the shot so you get the forest in the side… it changed the way they thought about the production, how they framed the shot.”

‘We’re the Plumbers’

With HDR likely to coexist with conventional pictures for the foreseeable future, trucks will be producing two separate outputs—but production has long demanded different outputs for different distributors.

Ralph Bachofen, senior vice president of sales and marketing at Triveni says his company deals less with the picture content and more with the way it’s moved around.

“I’ll differentiate between quality of service and quality of experience,” Bachofen begins. “We’re focussing on the transport layer. We do monitor the experience, we look at black frames, but… we’re focussing on the signaling aspects of it. We’re the plumbers.”

Distribution to vastly different platforms can make things even more complicated, as Bachofen explains. “A lot of people do a number of streams or production environments for different formats. You have very country-specific encoding requirements. How do I hand off these requirements to my main broadcast? How do I hand it off to my channel partners? You see a lot of encoding going on, a lot of activity in this field.”

The move toward IP, Bachofen reflects, makes for a lot of rationalization, with entirely new features as well as new maintenance demands.

“Can you make a box that does all of it?” Bachofen muses. “The answer’s yes—our StreamScopes handle multiple simultaneous stream inputs. You don’t want a box per stream, you want a single box that does multiple ingest.

“We have a large engineering staff who work on these requirements, and it’s not just video,” he adds. “There’s the vast requirement you get for security patches on the OS. The minute you put a device on an intranet, their IT departments require you to have the latest and greatest security patches.”

That unity of purpose can stretch the definition of test and measurement to provide an overview of an entire operation, a market need Triveni addressed at the 2024 NAB Show with the launch of Station Manager.

“Say, at 3 a.m., you want to do some datacasting… you add this in the Station Manager and you want to push this down to individual devices,” Bachofen said. “We look at whether this is a valid configuration. We help the engineering staff in each station to ensure they have valid configurations of the whole broadcast chain.”

Customer Feedback

Interra Systems is another QA provider that focuses on monitoring the entire production chain as well. The range of issues that can arise are more numerous than ever, particularly when it comes to HDR.

“Working with UHD, HDR files involves managing multiple aspects, including resolution, wide color gamut, high dynamic range, and frame rates,” the company wrote in a recent blog. “Each of these factors can contribute to different quality issues. Potential problems could manifest as blurriness, digital ghosting, color banding, and tone mapping. These issues may arise from mishandling wide color gamut, HDR metadata, or improper frame rate adjustments. It is crucial to adopt tools to address these conditions and ensure a smooth transition between HD and UHD content.

In the transition to UHD, nobody really had to do anything differently. Going to HDR, especially for people using test and measurement gear, I think over the next five years the best methodologies will find their way to the top."

Charlie Dunn, Telestream

Many media workflows involve up-converting 1080p HD content to 4K UHD and processing both standard dynamic range (SDR) and HDR outputs. However, mix-and-match scenarios introduce their own set of problems,” the company said. “Upscaling the resolution can introduce artifacts like blurriness, digital ghosting, etc. Likewise, frame rate up-conversion can lead to temporal artifacts for e.g., motion jerks. Upscaling the dynamic range and color can lead to color banding.

Most of these new features are already part of Interra’s BATON file QC solution, according to Interra.

“First and foremost, we have ensured that we have complete format support right from capture to delivery. This includes capture and distribution formats like TIFF, SonyRaw, DPX, ProRES, AVC, HEVC etc. On the QC side, we have already added support for Color Banding, Digital Ghosting, Aliasing, Motion Jerk, measurement of Light Levels for HDR and more. Feedback from the customers is key here.”

The technology for supplying that chain with HDR material, meanwhile, requires technology which is still growing in maturity. Charlie Dunn, senior vice president and general manager of Test & Measurement at Telestream, describes some new solutions to the vision engineering challenges of HDR.

As Dunn puts it, “a vectorscope in HDR space isn’t that useful. What’s more useful is a CIE chart [color space], but that’s a 1930s thing, and it’s not that great for determining if you're out of bounds. We’ve made a number of innovations—we’ve pitched a couple of papers at SMPTE, and we’re working on that toolset.”

Bringing the long-established competence of experienced people into such a new discipline requires some lateral thinking Dunn adds.

“People are so used to looking at a waveform and vectorscope to shade the camera. So, we’ve given them additional tools—one of them is a false color map. You can look at the greens on the pitch, the white lines, the reds of a jersey, so you can make sure they’re in bounds. If they’re not, they turn to a cyan or some unnatural color, so the operator can check the colors are right.”

The complexities of HDR have sometimes led to a degree of engineering conservatism, often with the result that color is limited to a range that’s actually somewhat less than could ideally be achieved.

“People are really interested in whether the CIE chart is going outside the P3 color space,” Dunn muses. “But that’s based on displays of 10 years ago. I have a feeling that’ll go by the wayside. I don’t see a lot of people doing that—I think it’s a problem they currently have and is not something they’ll constrain themselves to going forward.”

With that in mind, Dunn says, Telestream has sought advice from people who do this on a daily basis.

“Someone like Sky has some tremendous engineers, and we’ve worked really closely with them on adjusting our tools,” Dunn said. “They have a really long roadmap for us of things they’d like to see. They're looking at it from the point of view of how can I make things easy for the operator. That’s how false color came about, that’s how the luma-qualified CIE charts came about. I’d say on a scale of 1-10, we’re probably at a three. There’s a lot of ground for us to cover.”

The transition that’s in progress, Dunn says, is not quite like those which have come before.

“A lot of people are doing things in different ways. In the transition to UHD, nobody really had to do anything differently. Going to HDR, especially for people using test and measurement gear, I think over the next five years the best methodologies will find their way to the top. How people build their facilities, what they make remote, what they decide to put in the cloud, on the basis of having experience. We worry about the screen area which is ten inches across—we worry about how much information we can display in a small space!”

“But it’s good for us,” Dunn concludes. “It means they need more test equipment!”

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.