Celebrating a Century of NAB Shows

The ‘long and winding road’ to the centennial gathering

With the curtain set to rise on the 2023 NAB Show and the event having reached centenarian status, it’s interesting to examine how it came to be and follow some of its twists and turns in going from infancy to becoming the “biggest and best” gathering of broadcasters and content creators on the planet.

Its origin is closely intertwined with the launch by Westinghouse of KDKA radio in late 1920. This experiment in wireless delivery of news and entertainment on a regularly scheduled basis was a game changer, arousing public attention as never before. Soon new stations were taking to the air on almost a daily basis, with hundreds in operation in just a relatively short time.

With no established precedents or business models to follow, some of these first-generation broadcasters recognized the value in banding together to share knowledge and protect common interests, leading to the chartering of the National Association of Broadcasters in April 1923 and the first-ever “NAB Show” held later that year.

While little information survives, we do know that it was a single-day affair attended by only a few, and by later standards would seem rather anemic, with activities mostly centered on business matters such as performance royalties, the need for additional spectrum (a concern even then), and regulatory issues. As there were few equipment manufacturers, the technology displays were not a part of that show. (Exhibits at early NAB Shows came chiefly from the NAB and member stations. Technical displays did not appear until the show’s second decade.)

A Show For All Seasons

While the NAB Show is a rite of spring for many—seemingly always occurring in April and always in Las Vegas—this April/LV pairing is relatively recent. (Also, for many years the event was referred to as a “broadcasters’ convention.”)

New York City served as the backdrop for that 1923 show, with the event taking more than half a century to reach Las Vegas for the first time, and not becoming a yearly event there until 1991. After spending its first five years in the Big Apple, the show was moved to Washington D.C. in 1928.

Seven years later, it began to move around, convening in Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles, Detroit, Colorado Springs, San Francisco, St. Louis, Atlantic City, and even trying out resort hotels in White Sulfur Springs, W. Va., and West Baden, Ind.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Since its inception, the NAB Show has been hosted by no less than 17 cities and in almost every month, skipping only December and January, and taking 20 years to convene in April for the first time.

A heavy snow slowed down proceedings at the November 1932 conference, triggering a schedule reevaluation that pushed the event—with one exception—into warmer months from then on. (However, even that didn’t guarantee good weather at the late-March 1987 Dallas show, where snow showers and bitterly cold temperatures greeted attendees.)

After a Century, Who’s Counting?

Even though the show has been scheduled every year from 1923 on, the recent pandemic forced two cancellations, and the 1945 wartime event was kyboshed by a government order directed at freeing up transportation and lodging for military and defense industry personnel. (The directive banned meetings of more than 50 persons from outside the community hosting the event).

And technically speaking, there was no “NAB Show” from 1951–1957, as the organization temporarily rebranded itself as the NARTB (National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters) to recognize TV’s rise to prominence. The yearly gatherings continued, however, under the NARTB banner.

Broadcast technology was initially only a small part of early NAB Shows, but as the annual event entered its second decade, tech began to command an increasingly greater share of attention, with the 1935 program including a report on the status of television in Europe, and the first mention of an NBC Show “engineering committee” meeting found in a report on the 1936 convocation. It was small by later standards—eight persons, with WSM’s legendary Jack DeWitt serving as chairman.

Several technical displays were featured at the 1937 event, with exhibitor Western Electric unveiling one of the first commercial audio processors, its model 110A “program amplifier.”

State-of-the-art tech made its presence known in a really big way at the 1939 Atlantic City, N.J. show, with RCA and NBC engineers setting up “high-definition” 441-line cameras and encouraging attendees to be “televised.” Photographic screen shots made it possible for those conventioneers posing before the iconoscope cameras to prove it to folks back home. As summed up by a trade publication: “…the photos will undoubtedly be cherished in later years as relics of the pioneer days of television.”

That 1939 show also included an eerily prophetic comment from New York Times radio editor, Orrin E. Dunlap Jr. “Today it may seem that television is creeping at the pace of a glacier. But by 1950 broadcasters will be deep into… television. The ice age will not last forever.”

(Dunlap’s address was read by an NAB staffer as he was unable to attend the show.)

‘First Looks’

In addition to providing many attendees with their first look at television, the NAB Show has also served as the launchpad for many more broadcasting technological innovations. New breakthroughs introduced included color, 3D and HDTV; UHF transmission; ENG; communications satellite linkage; timecode editing; the dawning of digital technology; server-based video playout; solid-state transmitters; chip sensor cameras—the list goes on and on.

Perhaps the most memorable tech rollout occurred at the 1956 Chicago NARTB, with Ampex ushering in not only a new technology, but a sociological game-changer with their introduction of the videotape recorder. The unveiling had been kept secret, and when wraps were taken off, the machine instantly became—and remained—the focus of attention at the show with the electronics firm receiving orders for some 80 of the $50k VTRs (more than $44 million in today’s money).

The number of attendees and exhibitors has risen steadily since the inaugural 1923 event. Over the next decade, hundreds attended, eventually surpassing 1,000 as the 1940s began, and has continued to climb almost every year. (In addition to the “VTR unveiling” the 1956 show is remembered for a (then) all-time high attendance that exceeded 4,500.)

By the time of the 1977 Washington show, registration had swelled to nearly 13,000, totally overwhelming the city’s limited convention resources. (There was no convention center then, requiring the conference to be spread over three hotels connected by shuttle buses.) Hotel rooms were also in short supply, leaving upwards of 100 registrants with no place to stay.

Feathers were ruffled so much that the NAB vowed not to return the show to Washington until at least 1984, (it never did). Broadcasting magazine summed things up: “The NAB passes but D.C. flunks.” (A similar lodging issue at the 1947 Atlantic City show also earned that city a spot on the NAB’s “no more shows there” list.)

The number of attendees has continued to grow, hitting more than 100,000 by the 1990s. The number of exhibitors and exhibit space has increased correspondingly, with more than 1,800 spread across more than a million square feet of floor space in 2016.

Although attendance at the first post-pandemic show was substantially down from the show’s all-time high, the 2023 NAB Show will likely see an even higher number than the 52,468 who registered for the 2022 event. We hope you will be one of those who help swell that number as this “show of shows” moves into its second century!

Sidebar:

Moments of Drama

NAB Show veterans know that they can sometimes expect the unexpected—sometimes above and beyond the unveiling of a revolutionary product, especially as high-level government officials, members of congress and even heads of state occasionally make appearances. At least two of the shows are especially memorable in this regard.

An appearance at the 1941 NAB Show in St. Louis by then FCC Chairman James L. Fly sparked political fireworks that made headlines across the country. Just days before the show, Fly released a draft of new rules that would greatly impact business relationships between networks and their affiliates. The Commission’s “Report On Chain Broadcasting” quickly met with condemnation from major networks and NAB alike.

Verbal blows came to a head at the show with past-NAB President Mark Ethridge lambasting Fly and the report, and Fly countering by repeatedly referring to the NAB as a “so-called” organization and likening the way the broadcasting industry operated to a “dead mackerel in the moonlight…that both shines and stinks.”

Following Fly’s remarks, then-current NAB president, Neville Miller, called for a congressional investigation of the FCC, and questioned whether “the state of mind exhibited by Mr. Fly qualifies him to be chairman of a government agency calling for judicial impartiality.”

Broadcasting magazine’s Sol Taishoff described the politics unleashed at the show as “the most tumultuous of its 19 years,” adding “For acrimony and invective, the convention had no parallel in NAB annals, and it will probably be recalled in radio history as the “'Battle of St. Louis.'"

(Fly was a no-show at the 1942 event.)

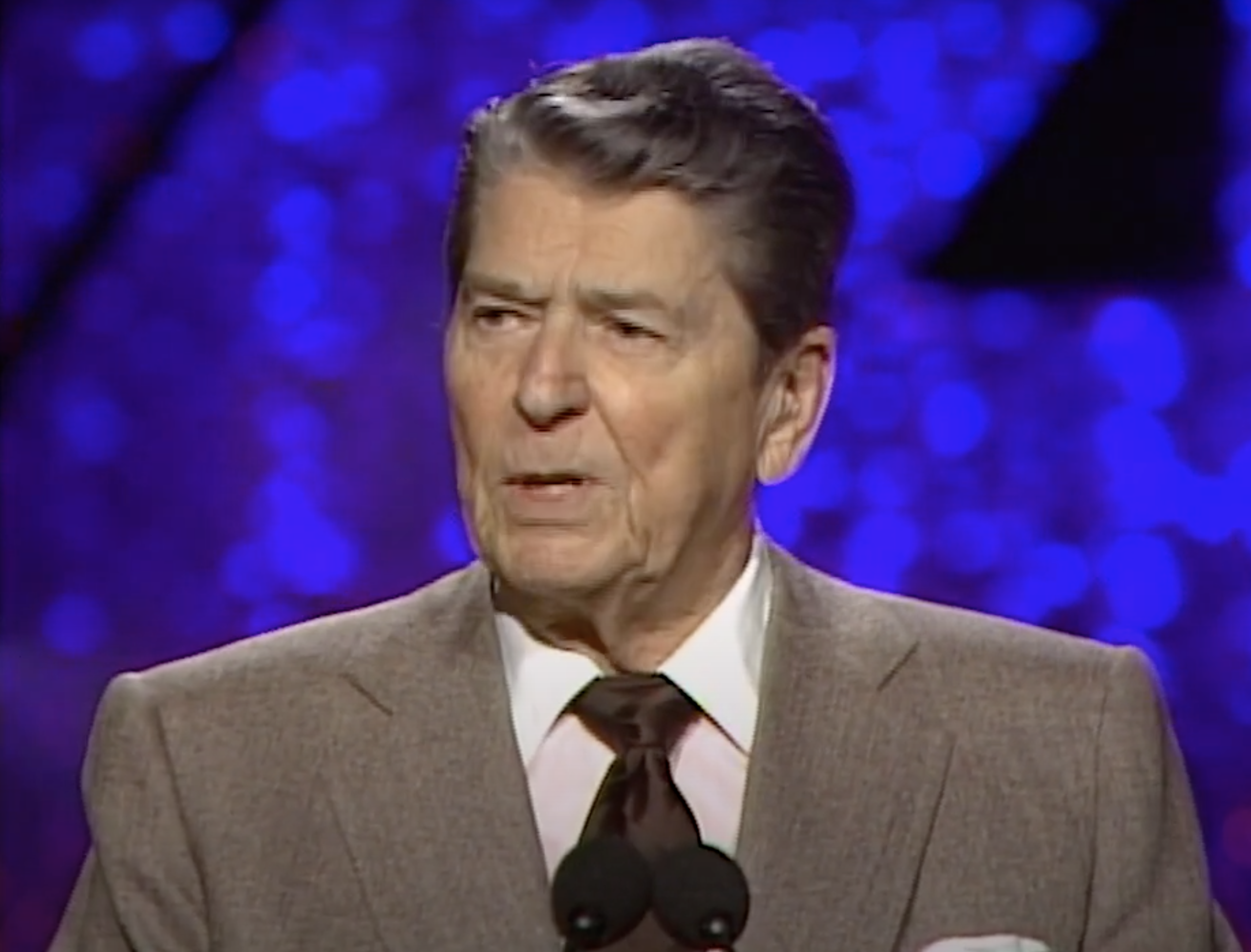

A half-century later, an anti-nuclear activist managed to slip past security and onto the dais at the 1992 Television Luncheon where former President Ronald Reagan was receiving the NAB’s Distinguished Service Award. Before the intruder was subdued, he managed to smash a large crystal statue that had been presented to Reagan, startling the former chief executive and showering him with glass shards.

Fortunately, Reagan was not injured, the protester was wrestled to the stage and removed, and the former president continued with his speech.

However, there were plenty of frazzled nerves among those who recalled John Hinckley Jr.’s 1981 assassination attempt on Reagan (which occurred rather ironically at one of the three hotels hosting the final NAB Show to be held in Washington).

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as editor-in-chief of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a Life Member of the IEEE and the SBE.