For M&E, Saving Money While Saving the Environment Is Not Either/Or

Raising awareness is almost as challenging as adopting sustainable practices

It’s easy to get the impression that the film and television industry has largely picked the low-hanging fruit of sustainability. LED lighting is both an environmental and a financial boon: reduced trucking, crew, generator and fuel costs have never been a hard sell to line producers. Moving beyond that, though, takes new ideas—especially given the current economic circumstances.

People at every level of production have their part to play, but those who make a living hauling lights around back lots are often aware that the ability to have nice things comes from the very top.

Matt Rivet, partner at Altman Solon, a consultancy focused on media and tech, works with corporates—from studios to broadcast and cable networks to streaming services—and all the tech that supports them. He also supports investors in media companies and assesses the commercial merits of said investments.

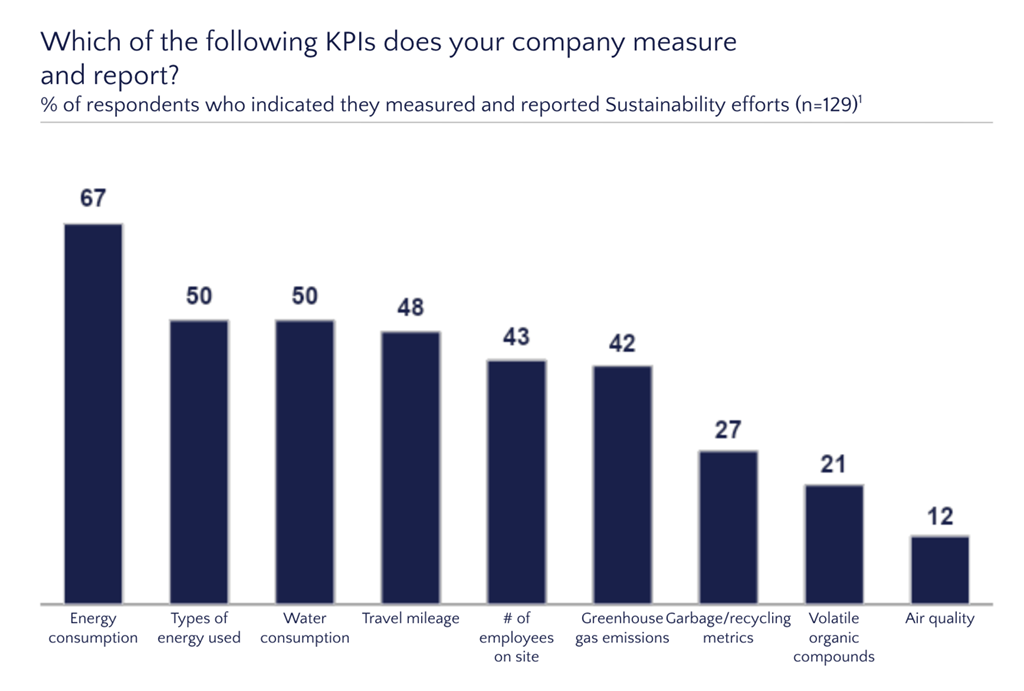

“Generally speaking, I think there’s a shift toward sustainability, broadly," Rivet says. “The most obvious place that everyone goes is energy consumption. It feels like it’s a place where there is a very obvious way—quick wins is where it’s at. The other things are waste, water, how you buy, where you buy from.”

Taking popular new ideas and making them part of the solution can help take the sting out of change, Rivet adds. “One of the things we highlight in our report is travel mileage. Virtual production can potentially be one of those things that helps reduce the amount of travel that needs to be done.”

Virtually Obvious

Sony Pictures, Rivet relates, has run the numbers on at least one kind of production. “This is not analysis we did—it’s Sony Pictures’ Greener World initiative,” he says. “They compared two productions with scenes that were shot on location and in a VP studio.

“The comparison in terms of the overall emissions was quite stark. I don’t know the exact numbers but it was something like 15-25% less emissions.” The embodied carbon of a high-end virtual production stage, of course, is far from zero, but it can be amortized over multiple productions.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The hugely varied tasks required of film and television production have always made coordination difficult.

“Media and entertainment is inherently disparate,” Rivet reflects. “People are going to various places doing various things, and it’s hard to consolidate. We’d love to, but it’s just not practical … in our data, there’s a lack of awareness of benefits of sustainability. Sixty-eight percent of folks said that’s why they hadn’t prioritized sustainability. Fifty-six percent said there was not enough of an incentive, or high up-front costs.”

“Media and entertainment doesn’t have to be a first adopter,” Rivet points out. “Other industries will go there. The future here will likely be some level of moderate change over some period of time.”

Even so, that time may not be now or next week.

“I’d be remiss if I didn’t remind you that M&E companies are under a lot of financial stress," Rivet says. “They’re looking for opportunities to improve efficiency and save on their cost basis. And I do believe, if you model it out, there’s a long-term benefit for sustainability because it will create some savings. The push and pull is that they can be interested in doing those things, but they have to balance that against the realities of operating their business.”

The Buy-In

Ben Stapleton, executive director of the U.S. Green Building Council California, has seen firsthand how critical boardroom-level support can be. Even with that support, Stapleton counsels that getting the most from any sustainability initiative often means more than a simple equipment exchange.

“It’s about working these ideas into the production from the beginning, not as an afterthought,” he says. Generators are an example … people use generators and run cables, it’s expensive and dangerous and creates a bunch of carbon. You can just distribute the power into smaller batteries all around the production, save money on wiring and have a safer set.”

Broadening the scope of sustainability efforts beyond energy doesn’t necessarily mean they need to become expensive, Stapleton continues. One concept involves direct reuse of resources such as the lumber used to create often short-lived sets.

“Waste is clearly an important area," Stapleton says. “How do you approach material reuse, prop reuse? It’s not just creating new props and backgrounds. There’s a ton of waste that comes out of that process—how is that waste managed? Yes, it is a sustainability principle to figure out how we can reuse, but it’s also going to be cheaper to reuse.”

Again, though, the imperative to make that happen needs support throughout the organization. “Part of the challenge is—let’s say—you’re someone who’s managing the set design and the props,” Stapleton adds. “If you don’t have buy-in from the person who’s handling the financial and operations side, they’ll come to you and be like: ‘What are you doing here? That’s not how we handle things.’ If people have been [trained] and understand why these decisions need to be made, they can approach it differently. It doesn’t add cost and delay.”

Moving to the Grid

Mark Thornton, a London-based lighting technician, has enough experience at the sharp end of film production to put him in a good position to assess new ideas. The knowledge that electric mains flow beneath most city streets—often just feet away, but inaccessible—led Thornton to get involved in a project to provide access to that power at key locations.

“I was contacted by Film London who were talking about putting this mains post into Victoria Park,” Thornton recalls. “They’d already done most of the work on it, so I got involved in a consultation group and said the place where it is is brilliant, but here’s some suggestions for the box itself. I suggested a few ideas of how to manage it, being a remote location away from Film London’s base and not something they’d normally do.”

Power drawn from the grid will usually be cleaner—and certainly quieter—than power that is generated on-site.

“That was the whole point of it being at Victoria Park,” Thornton adds. “They had a lot of fairgrounds and live events, concerts. They were trying to make sure people were able to use the post—actually it’s a rather large box—rather than bring in generators. The issue is not only sustainability and environmental impact, it’s also noise. Even when we go on the route of having battery generators, we have to charge them somewhere. The idea is that a production could go to Film London and say, ‘We have a 25kW battery pack that we’d like to charge up on a regular basis’ and it’d be up to them to charge a cost.”

Rules in the Way

That sort of idea requires no new technology and comparatively little investment; as so often, the barriers are administrative. Here, Thornton refers to another idea that seems to combine high utility with low inconvenience, but which has found itself enmeshed in red tape.

“One of the ideas is that we get access to EV charging points. There is a company that makes towable batteries … they use the Tesla power packs and the brains so they can go and use the Tesla supercharger—but if you do that in central London, it doesn’t have a [license plate], so it doesn’t have an account.

M&E companies are under a lot of financial stress. They’re looking for opportunities to improve efficiency and save on their cost basis.”

— Matt Rivet, Altman Solon

“It’s the rules that seem to be getting in the way,” Thornton muses. “The infrastructure is technically possible but there’s someone with a pen somewhere who says you can’t do that. As an industry, we’re doing pretty well, moving toward LED light sources. The physics is not going to change, but if you look at the wider country, there’s a lot of renewables, wind power, wave power, as soon as they start phasing out all the natural gas … There’s a really good web site called Gridwatch that I’ve used quite a few times to highlight where the [U.K.'s] energy comes from, and the closer natural gas gets down to zero, the better off the country will be.”

While those big-picture issues are addressed at a societal level, Thornton points out, there are still some very accessible avenues to explore. Particularly, he proposes one very general principle which will be painfully familiar to people experienced with single-camera drama—and talismanic of the drive for sustainability as a whole.

“There’s a bit of people not knowing what they want,” he concludes. “It’s about planning—right across the board, from personnel management to kit ordering to logistics. If we were able to plan, if someone up the food chain made a decision early in the process, we could plan better. The problem we have as an industry is everyone leaves it to the last minute.”