The Evolution of Intercoms: How Communication Tech Transformed Television Production

From telco ‘party lines’ to IP and the cloud

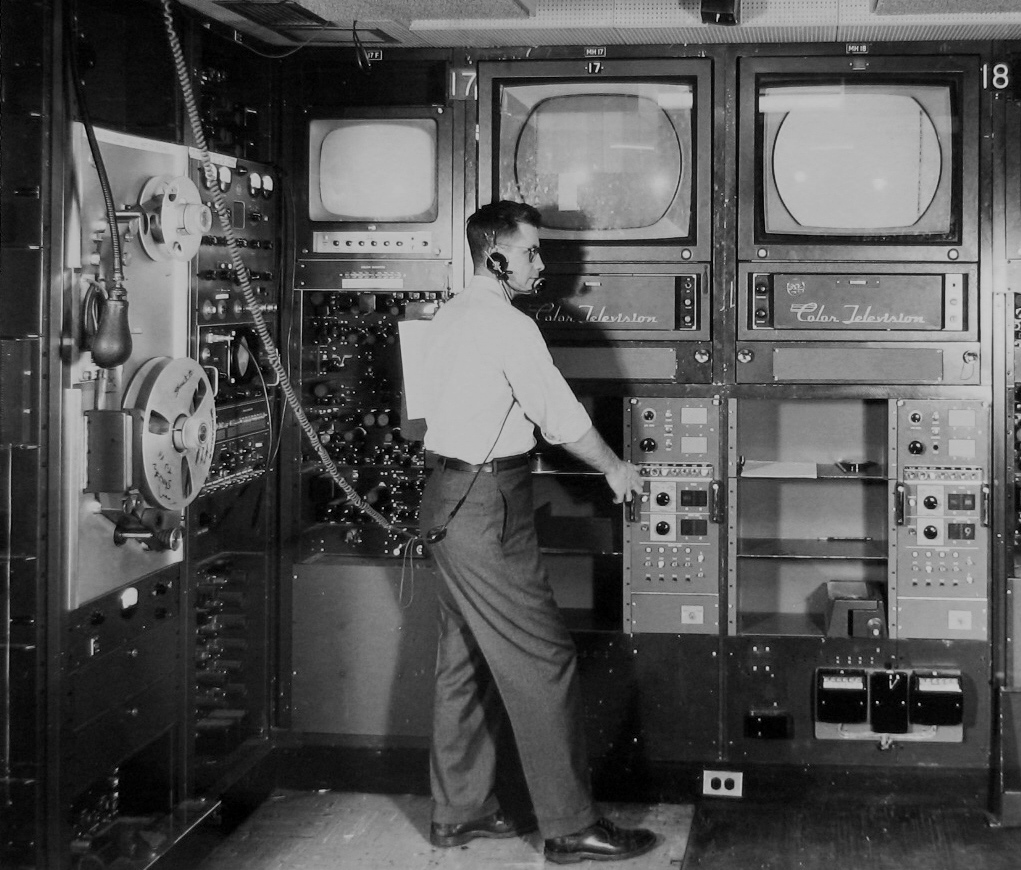

As television moved out of the laboratory and into regular broadcasting schedules during the decade of the 1930s, it was obvious early on that the “hand signal” methodology used in radio broadcasts for communication between a show’s director and performers in the studio wouldn’t work. Television’s glaring lights and much larger studio spaces made such visual communication either very difficult or impossible.

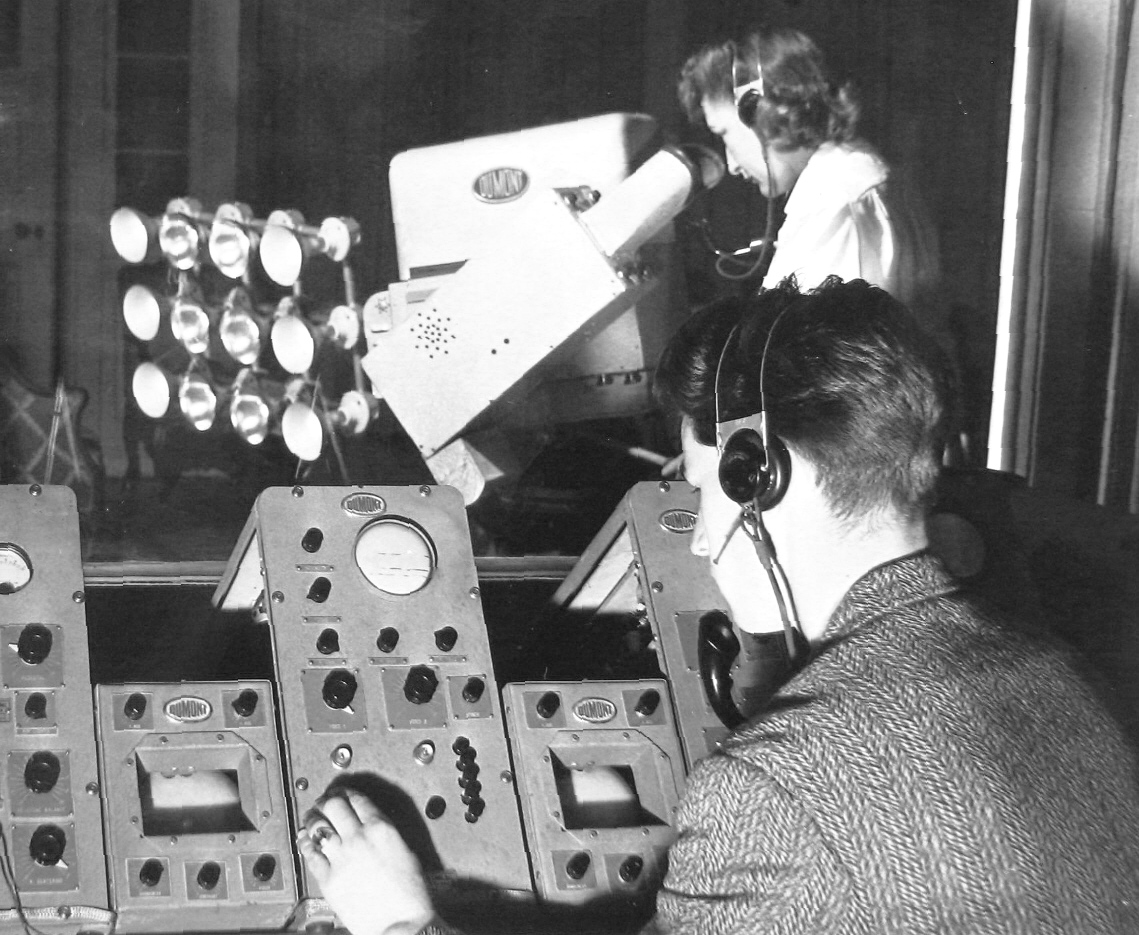

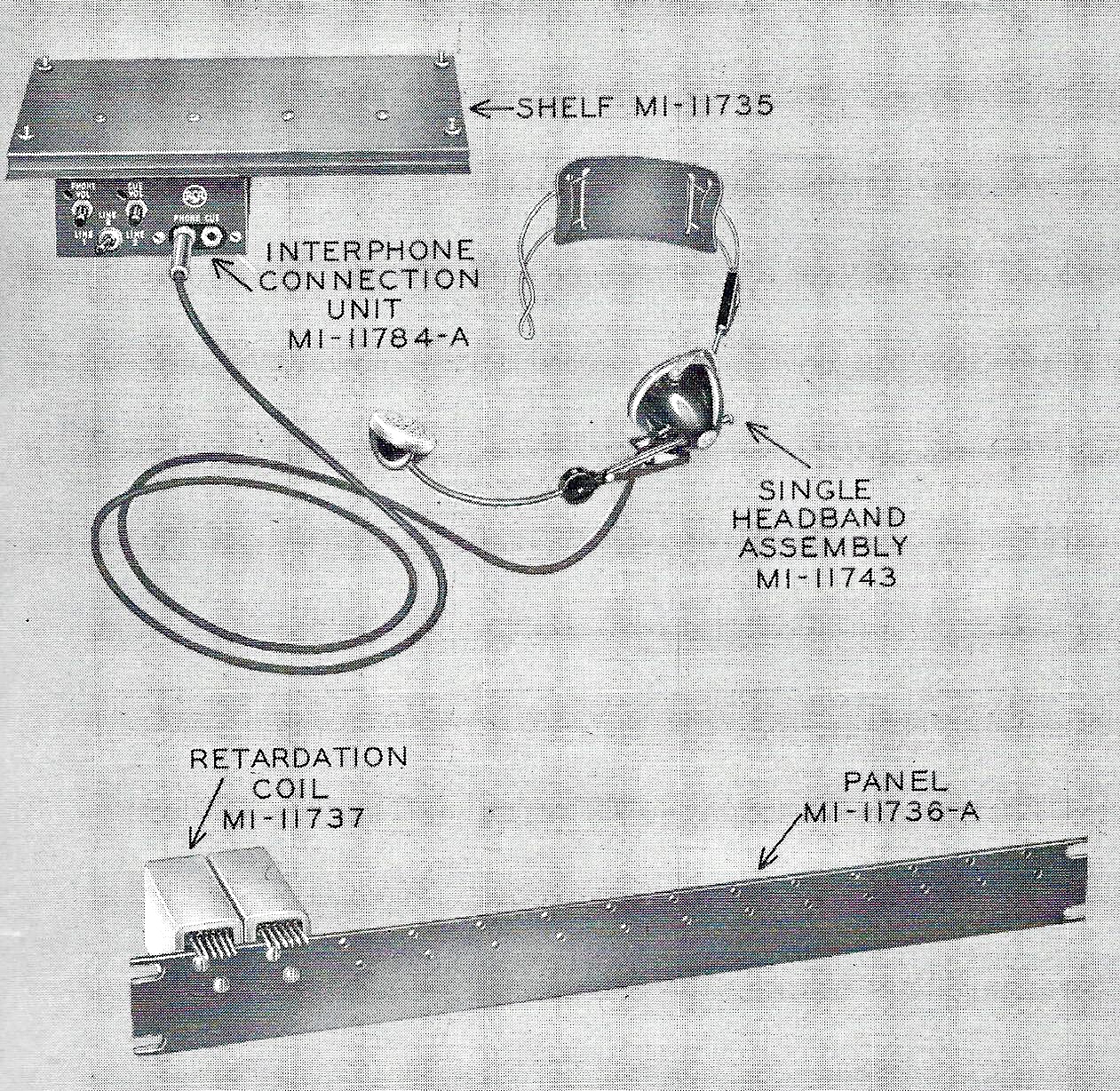

As a solution, early TV broadcasters cobbled together their own intercom systems from available telephone company technology (switchboard operator headsets and carbon microphones) to enable “party line” communications among all crew members.

Although there was much technological progress in other areas such as higher power transmitters, UHF, color and videotape, during television’s post-WWII boom, intercom technology largely remained stagnant.

A few manufacturers such as RCA, began to offer commercial pre-packaged versions of the telco-technology party line systems, and others, such as Telex (an early provider of hearing aids) developed improved operator headsets with better ear cushioning and a headphone for each ear that allowed wearers to hear both intercom traffic and program audio, but that was about as far as it went for the next couple of decades.

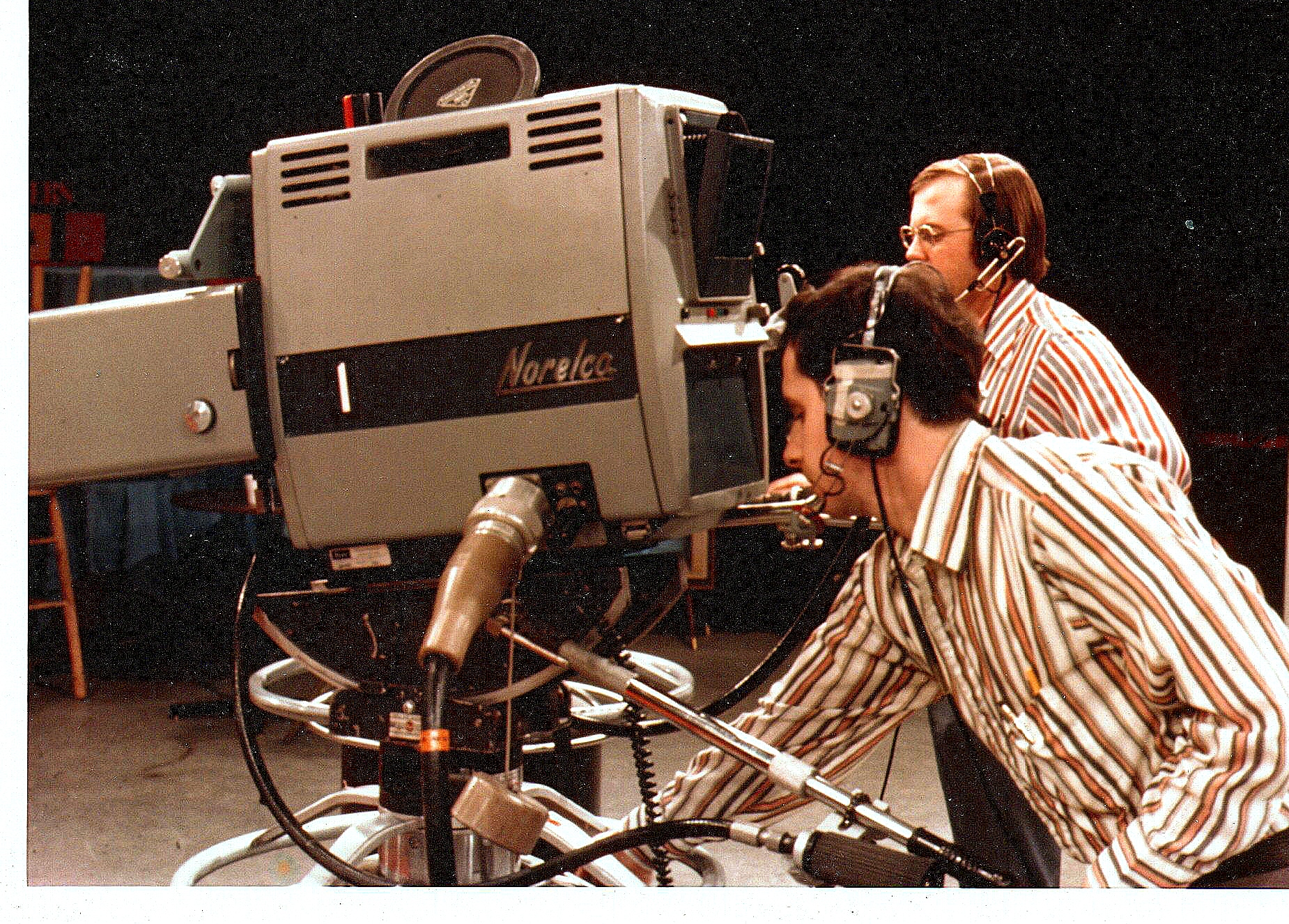

Gone forever were the days of two-camera black and white remotes. To meet such expectations, the networks added more and more camera positions, and enhancements such as instant replay, electronic graphics, and on-field mics for capturing officials’ calls. All of these involved operators who needed to be “on headsets.” With these additions in support personnel, the limitations of existing intercom technology soon became apparent.

“As you continue to add stations, the circuit impedance goes down and levels go down,” noted Dave Brand, whose career spans some 40-years of involvement in intercom technology, and who, with his son Stephen, established Intracom Systems of Malibu, Calif. “These early systems were very limited as to how many users they could accommodate.”

Jay Ballard, who spent much of his broadcast career with NBC agreed, noting that such “two-wire” telco technology had been the norm even in the mid-1970s when he started at NBC’s Washington, D. C. O&O, WRC-TV, and also at the network’s New York headquarters.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

“Adding stations lowers levels on a two-wire system,” he said. “To try and get around this, NBC New York had employed multiple two-wire circuits for isolation when I went to work there.”

Brand observed the next step in intercom evolution came from Clear-Com, a fledgling San Francisco company started by audio engineer Charlie Butten, and Bob Cohen, owner of a live sound business.

“Bob put together a different type of intercom system,” recalled Brand. “Instead of using voltage-sourced user stations where each added station lowers the impedance and level, he came up with the idea of a current-sourced system with high-impedance devices. This way you can stack a whole lot of stations together before you notice any significant loss.”

Brand recalled that almost simultaneously with Clear-Com’s push for a better intercom system, another group of garage innovators— Douglas Leighton, Stan Hubler, and Rick Karwoski—teamed together to create enhanced intercom technology, which included two-separate communication channels, ultimately founding RTS Systems.

According to an RTS company history, “(our technology) replaced a system patched together with telephone headsets, adapter boxes, and cables… (which) barely worked with very few stations connected together.”

This early RTS system accommodated as many as 50 stations, and provided “good clean audio as loud as the user wanted.”

“Europeans understood the need for four-wire early on,” said Ballard. “Coverage of sports, especially the Olympics, necessitated it. NBC had tried using multiple buses to accommodate an increased number of users, but this wasn’t a very versatile approach, as a guy in videotape didn’t need to hear what was going on in camera control. It was around 1970 that the four-wire approach began to take off in this country, with ABC leading U.S. networks in moving away from two-wire technology.”

Ballard noted too that coverage of national political conventions was also a driving factor in the eventual movement away from two-wire technology.

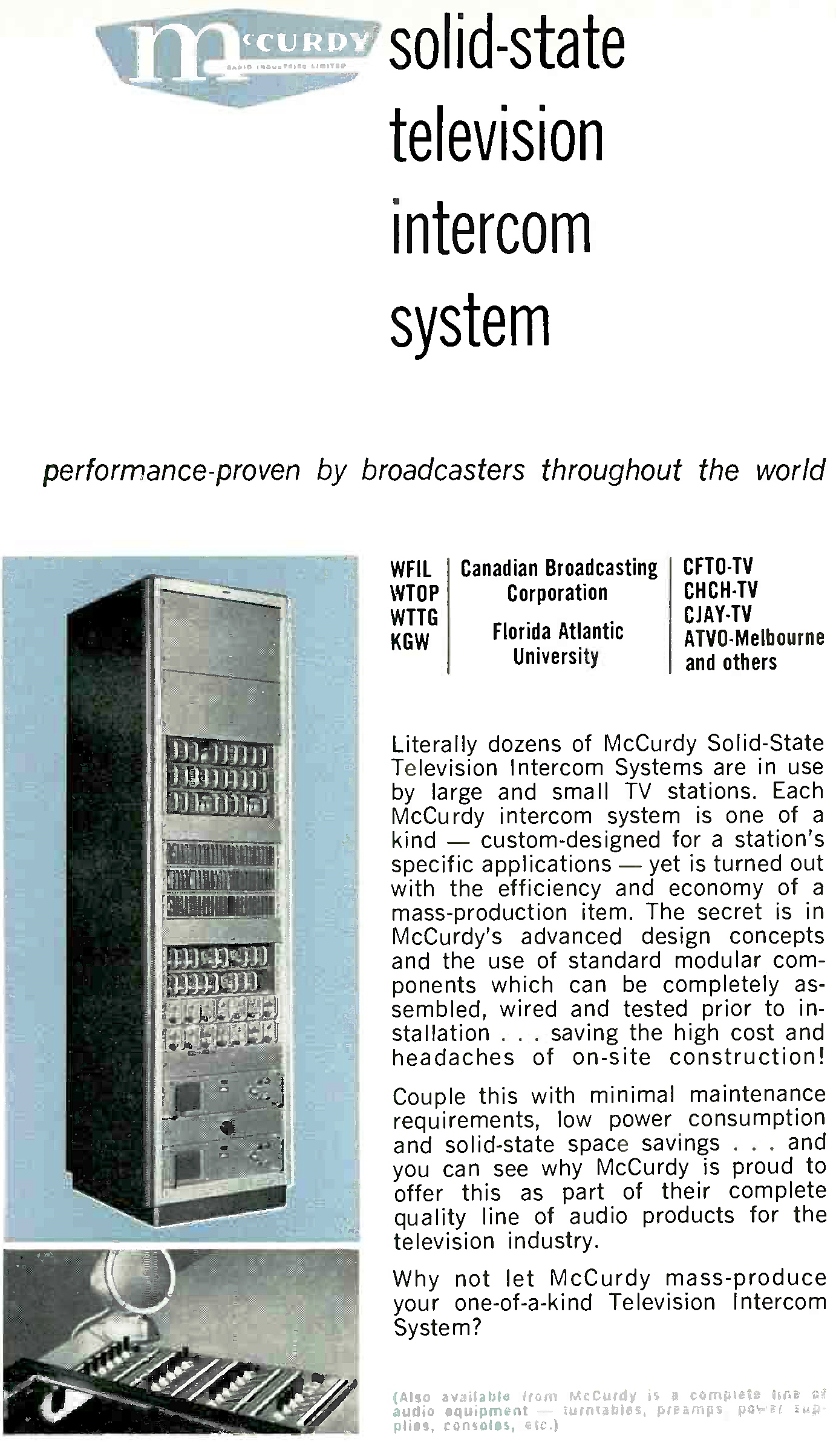

“The sort of convention coverage that began in that era required directed and isolated communications,” Ballard said. “A lot of manufacturers got into the business then, with companies like McCurdy addressing this need early on.”

(Toronto-based McCurdy Radio Industries, which began operations in the 1940s, was pivotal in moving from party line to individually directed intercom communications. The company had been delivering four-wire hardware, including necessary switching matrices, long before there was a U.S. demand. McCurdy advertised four-wire matrix-switched intercoms in U.S. trade journals as early as the mid-1960s. Another Canadian company, Ward Beck Systems (WBS) was also an early supplier of four-wire gear.)

Entering the Digital Era

The emergence of digital integrated circuits during the 1970s was another driving force in intercom system makeovers, with companies beginning to offer such features as computer (microprocessor)-controlled switching matrices and programmable key panels with LED (and later, LCD) alphanumeric key labeling.

Digital signal processing was soon to follow, with manufacturers now touting “broadcast quality” audio. Large multiconductor intercom cabling also fell victim to digital technology, with a single coax or CAT-type data cable able to handle both audio and control functions.

Switching matrices also grew in size, with manufacturers offering systems as large as 450 x 450 by the mid-1990s. It also became possible to link (trunk) multiple physically separated matrices to create extremely large systems.

Portable operator stations (aka “beltpacks”) were also developed, eventually with wireless connectivity that provided operators with a much greater range of movement than ever before.

“Systems then were very simple,” said Dugan. “There was a beltpack, a power supply and cables. Everything was hard-wired.”

This soon changed.

“The digital matrix became the core technology, and networking has taken over the intercom world completely,” he said. “Clear-Com and RTS now have 1RU units with wireless capability, connectivity through the internet, and hardwired connectivity all from the same box.”

Dugan observed that a really big technology leap occurred a dozen or so years ago when the first DECT (digital enhanced cordless telecommunications) systems began to appear. “DECT-based units now are the ‘bread and butter’ of today’s wireless intercom world,” he said

Dugan also noted that the move to wireless intercom stations has become universal.

“It’s not uncommon to have as many as 100 wireless beltpacks deployed when two studios operate side-by-side on a show,” said Dugan. The networks sometimes operate with several hundred beltpacks.”

The biggest problem in deploying intercom systems nowadays is not with the equipment, but in managing spectrum as a resource in which to operate, Dugan said. “At the end of the day, spectrum is the real estate where we build wireless systems, and that’s something that the FCC, and to some extent, manufacturers and consumers who lobby, will ultimately drive and impact.”

What’s Next?

Two members of the engineering operation at one of the country’s largest television broadcast operations, the Sinclair Broadcast Group, were asked to share their thoughts about advances in intercom technology, and to speculate where it may be going.

Paul Spinelli, SBG’s assistant vice president of engineering, opined that “this would definitely be the move to IP,” noting that earlier in his career, “the intercom filled half a rack; now you can do the same thing in a few RU and a switch.”

Charlie Straker, Sinclair’s senior director of cloud engineering and operations, agreed.

“It’s all migrating this way,” said Straker. “[IP] certainly makes things a lot simpler and more efficient. I would also say that there has been kind of a ‘democratization’ of intercom systems. For a long time, it was just RTS or Clear-Com. Now you’ve got companies like Riedel—all sorts of companies—that are really innovating in this space.”

“There’s also a lot of open-source intercom software out there, and some of this is evolving into paid-support models,” added Spinelli. “It’s quite good.”

Spinelli and Straker shared their thoughts about what TV production intercom systems might look like a few years from now.

Straker shared Spinelli’s observation regarding a universal movement to other IP formats.

“I see NDI kind of taking over Dante,” he said. “There are some companies already doing NDI intercoms. It’s just a matter of time before that gets picked up by the big boys out there. It’s all part of the democratization of everything. IP protocol makes everything cheaper for everybody. There are a lot of benefits.”

The two engineers also reflected on the pandemic-fueled changes in broadcast facility intercommunications; changes that have resulted in a communications modality likely unfathomable to those working in television’s early years.

“Covid drove intercoms,” said Spinelli. “Everybody’s got an intercom app now. I can talk with Charlie or anyone else in this building. It’s now ‘intercom anywhere.’—you just put in your wireless earbuds from your phone, load an app, and you’re communicating with everyone in the control room.”

Spinelli and Straker agreed that it’s just a matter of time before the hardware-based intercoms that have served the industry since its inception are destined to become pages in a history book.

“I’m the cloud guy,” said Straker, “And I would say that we’ll be getting away from having actual hardware frames and migrate everything to the client/server model where everything is software based.”

“I don’t see many facilities purchasing intercom panels anymore,” said Spinelli. “They’re going to web-based GUI virtual interfaces and a computer headset. Why would I purchase an intercom frame and panels at a few thousand dollars apiece when you can run a soft panel?”

Spinelli observed too that technology has reached a point where hardware really isn’t necessary for intercom systems; they could be driven by a cloud-based server.

“Suddenly you have an intercom at a really effective cost point,” he said.

“With a cloud system, you only spin it up when you need it, and then spin it down when you don’t,” Straker added.

“If you’re a production house or content center, you’d only turn it on when you have a customer,” Spinelli concluded.

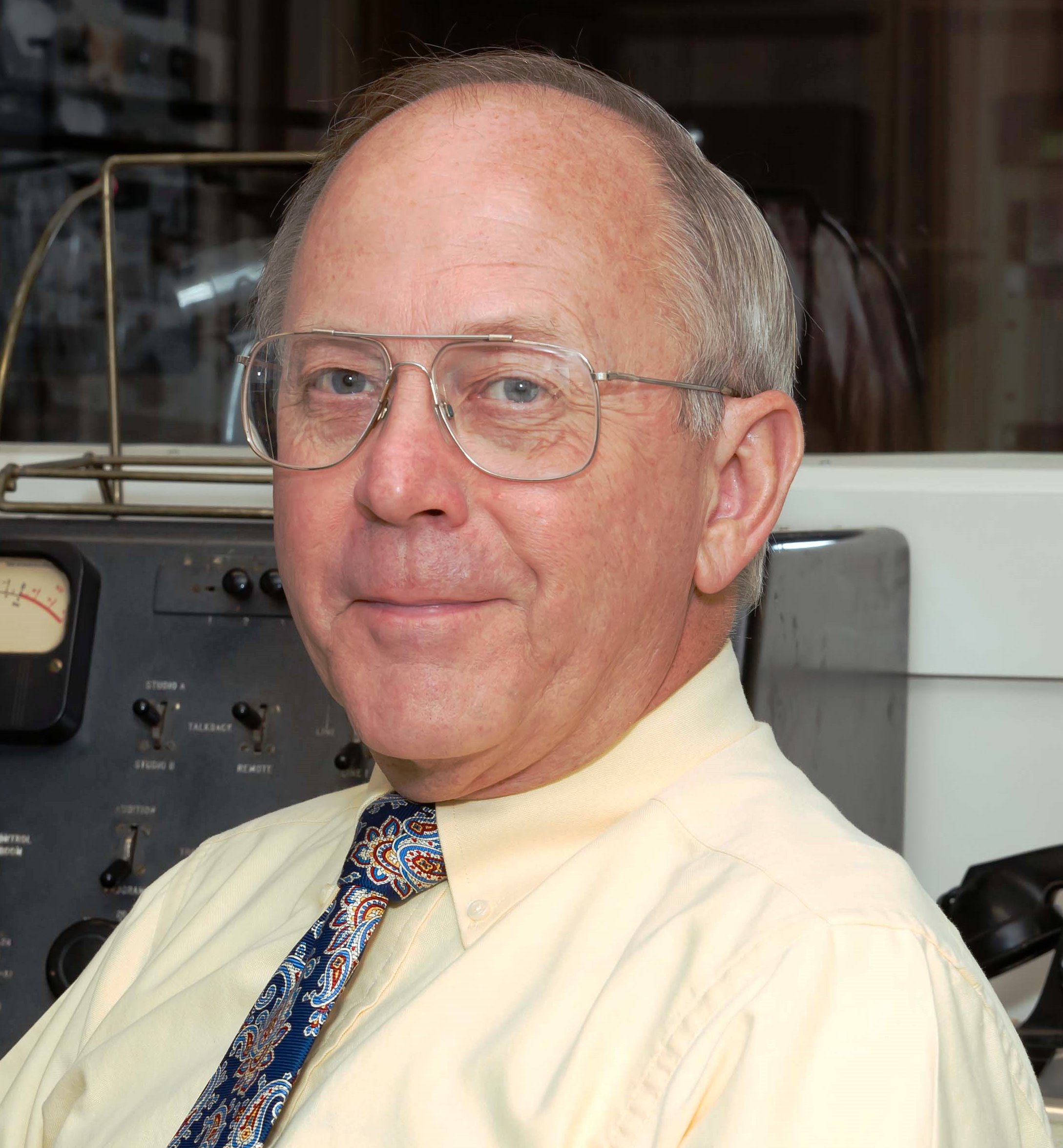

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as editor-in-chief of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a Life Member of the IEEE and the SBE.