The History of ENG, Part 3: Camera Advances Push ENG Into the Modern Era

Newsgathering gear got lighter, more compact and more reliable

This is the third in a four part series.

With the introduction of increasingly better and more reliable transistor types during the 1960s, broadcast television equipment steadily moved away from large and power-hungry vacuum tube designs to transistorized versions. The introduction of the integrated circuit also played a role in miniaturizing gear and making it more reliable.

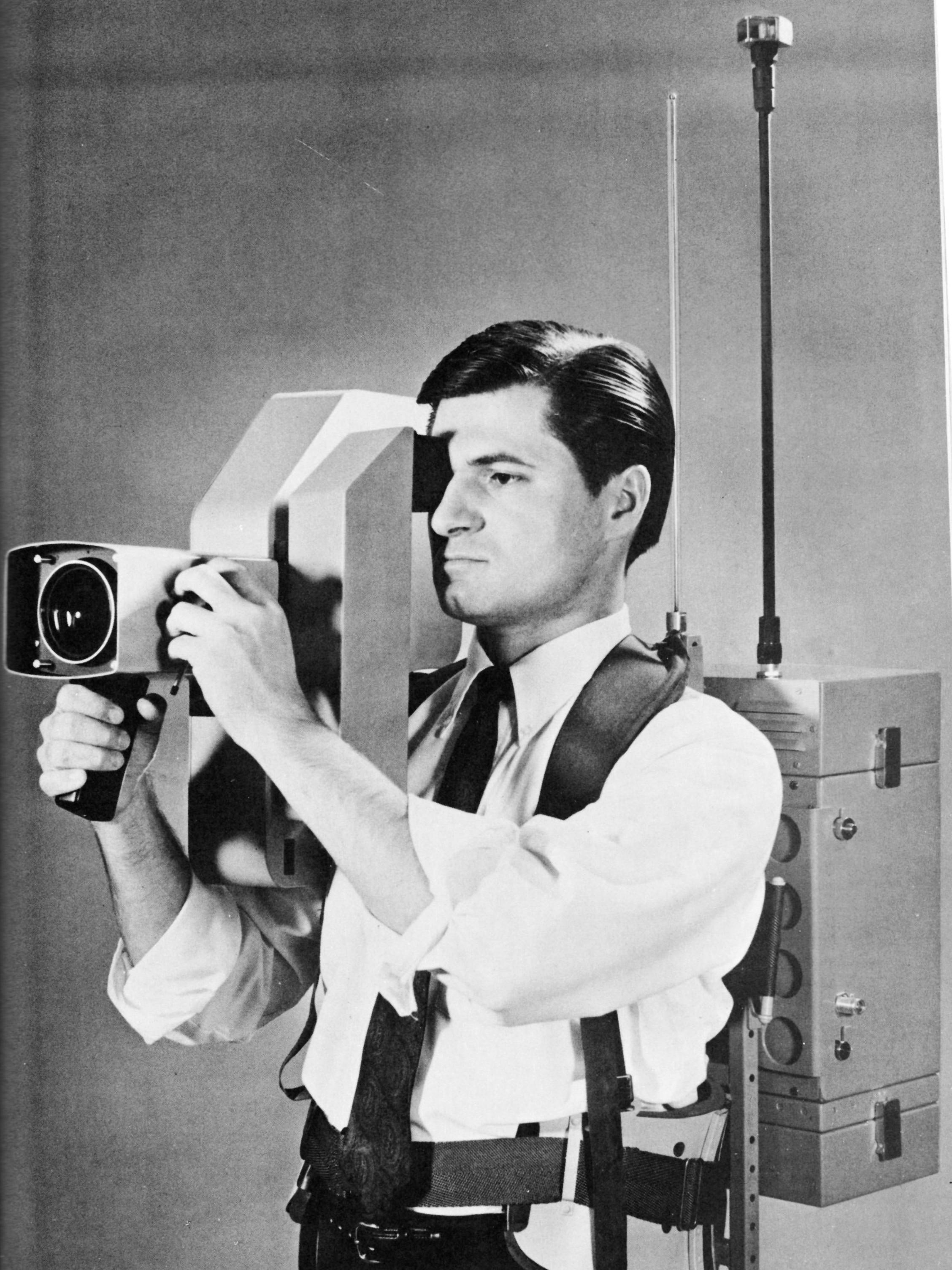

Camera Imaging devices also improved, with the Plumbicon and other tubes beginning to rival the performance of the much larger image orthicons. Color cameras shrank in bulk and weight—from units requiring several persons to lift and racks of support equipment—to models that could be carried by a single person (with support electronics contained in a separate package, usually in the form of a backpack).

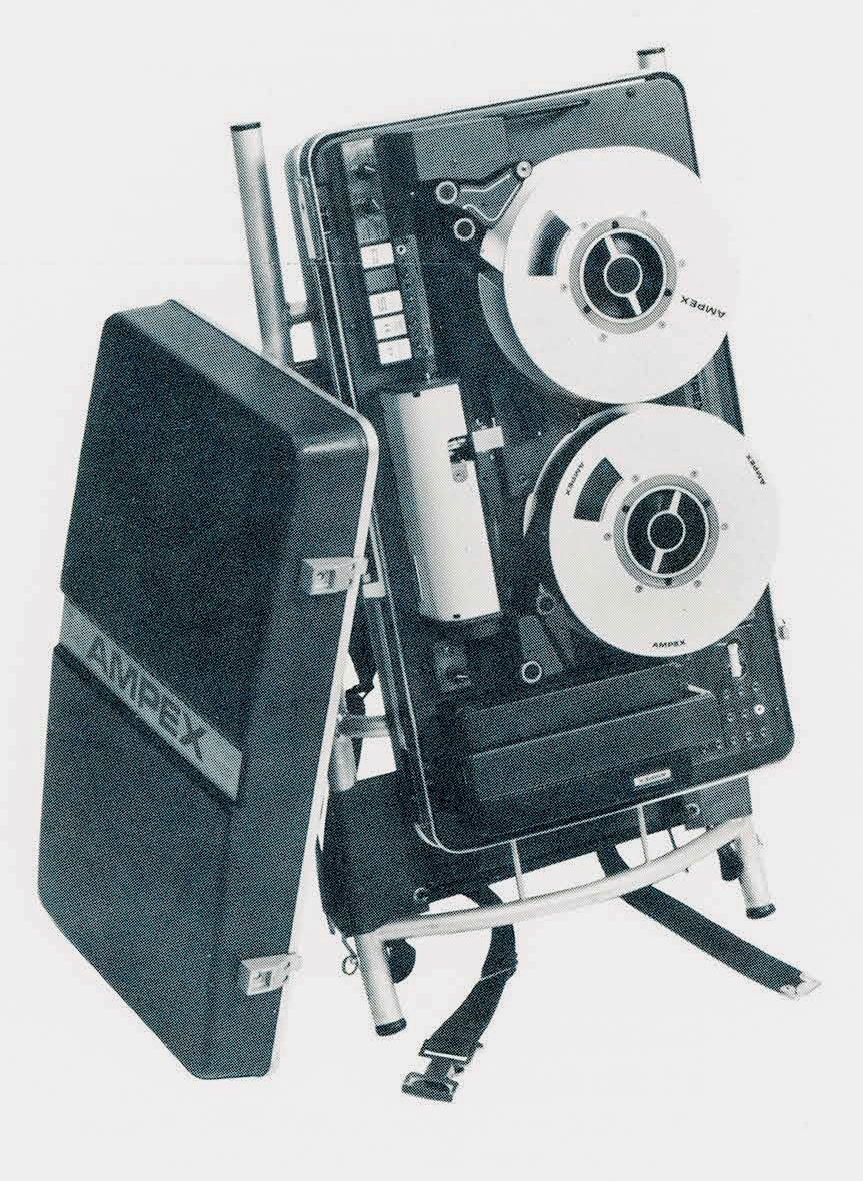

CBS Laboratories created such a device as early as 1968, the Minicam VI. RCA ushered in the era of self-contained portable cameras with the release of the TKP-45 in 1974. Video recorders also became more compact, with Ampex introducing a portable version of its “quad” machines, the VR-3000, in 1967. This rather revolutionary recorder was deemed “portable” in that its 55-pound load could be managed by one person and powered by batteries.

With this miniaturization of cameras and recorders, it was just a matter of time until someone decided to pair them and go out and cover a news event. Just who, when, and where this initial “modern” ENG initiative took place will likely remain a mystery; however, by 1974, at least several broadcasters and a couple of major networks were quietly trialing ENG.

Project X: ‘Anyone Talking About It Will Be Dismissed'

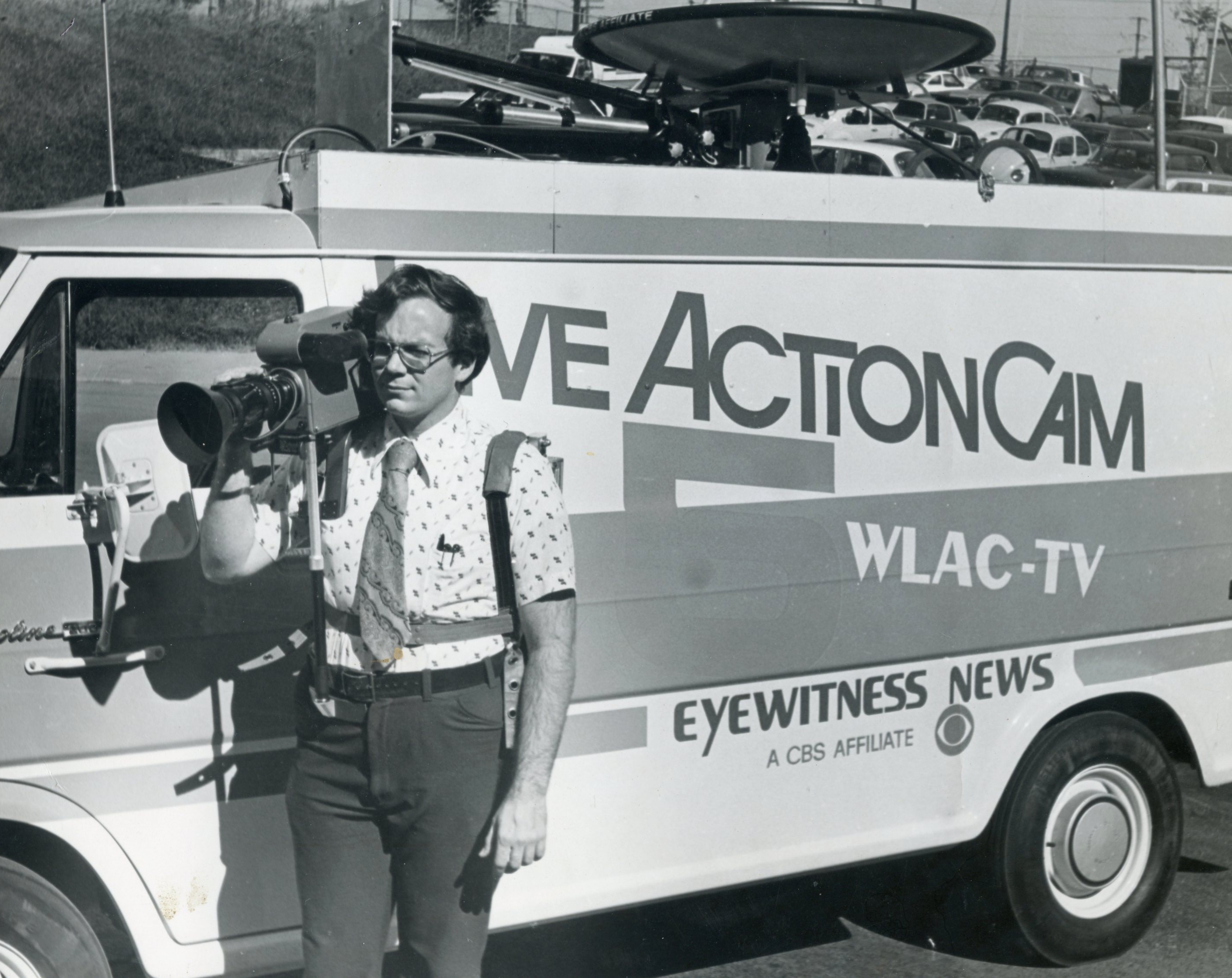

Nashville’s WLAC-TV (now WTVF) was one of these early electronic newsgathering adopters, and in mid-1974 launched a secret project to construct the first ENG vehicle in that market. According to one member of the engineering team who took part in the initiative, none of the personnel involved were allowed to reveal to other station members or others what they were working on, under the threat of instant termination if there was a leak of information.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

“Station management really wanted to beat the competition,” said Butch Smith, one of the six or seven WLAC-TV engineers assigned to the project. “We were told by the station’s director of engineering, Ralph Hucaby, not to reveal anything about what we were working on, under penalty of dismissal from employment.”

Smith said that work on the ENG unit took place in a locked area of the station’s basement and due to its secretive nature, one of the construction team dubbed it “Project X.”

“I’m not 100% certain when we went on the air with our first live transmission from the van, but construction started sometime in July and it took us three or four months to complete,” said Smith. “We beat the other Nashville stations considerably.”

According to Smith, the station selected Ikegami HL-33 cameras for the project, but after more than half a century, he is uncertain about the video recorder used. He recalled that, as the van was equipped with a 2-GHz microwave transmitter, a majority of the stories covered went live.

“We had a receive site on top of the high-rise Life and Casualty Insurance Company tower building, as they owned the station then. This was a 33- or 34-story building, and we could go live from just about anywhere around Nashville.”

The NAB Show That Heralded in the ENG Era

A year later, interest in ENG had increased to the point that the April 1975 NAB Show offered its first “workshop” on the subject, with show organizers not really prepared for the number of individuals who decided to learn about the new methodology. As the post-show issue of Broadcasting magazine headlined it, “ENG is SRO at NAB.”

“If you're not already into electronic newsgathering, get your toe in the water," declared Julius Barnathan, ABC’s then-vice president of engineering operations, and one of the workshop’s presenters. (Another was WLAC-TV’s Ralph Hucaby.)

Broadcasters, eager to learn as much as they could about ENG, stood three-deep at the rear of the room, and according to Broadcasting, “completely lined the side walls and were crouched or seated on the floor in front of the stage.”

Another presenter, Thomas M. Battista, vice president and general manager of then CBS St. Louis O&O, KMOX-TV (now KMOV), described that station’s ENG experimentation, observing that in addition to benefiting local news coverage, it also served as a pilot program for CBS’s eventual foray into ENG.

He noted that with ENG, KMOX-TV had covered 20% more stories in March 1975 than in the same period a year earlier. Battista stated that the number of technical personnel involved in news coverage at his station shrank from 56 to 50. (WLAC-TV’s Hucaby reported that he expected his station’s expenditure of $300,000 (almost $2 million in today’s money) would be fully amortized in six years.)

“If you put together a good system and come up with better news programs, you'll make loads more money and won't have to worry about the cost," said Battista.

If that weren’t enough inducement for attendees to start budgeting for ENG equipment—of which there was plenty at the show—ABC’s Barnathan offered two other incentives.

“The first key to ENG is the ability to ‘go live,’” he said. “The second is ‘to save your ass late in the afternoon.’"

(As an historical note, a few years prior to the KMOX-TV O&O implementation, the CBS network had trialed electronic technology as an alternative to news film, equipping a few two-person crews with either CBS Laboratories Minicam VI's (introduced in 1968), or the slightly later Norelco PCP-90 three-tube cameras and Ampex VR-3000 backpack two-inch quadruplex videotape recorders, introduced in 1967).

This approach, the use of traverse-scan videotape recording, allowed the field-generated tapes to be played directly on conventional studio VTRs. The camera/VTR package could scarcely be considered portable, however, with the recorder weighed more than 50 lbs. and the camera, along with its backpack support package, tipping the scales in excess of 40 pounds.

The technology did offer one real advantage for the network, though, as it allowed reporting and transmission of news in locations where no film processing was available. NBC also experimented with a similar equipment package, but declared that while it gave “excellent results,” the camera/VTR combo was “too bulky and heavy to replace 16mm film cameras.”)

How Best to Go ENG—‘Flash Cut’ or Phase In?

Likely as a result of the workshop, and perhaps out of a desire to provide better news coverage and save some money in the process, more and more stations followed Barnathan’s admonishment and dipped their toes in the (ENG) water.

One of those stations taking Barnathan’s advice was KGLO-TV (now KIMT) in Mason City, Iowa. David Ostmo, the Sinclair Broadcast Group’s regional engineering director, and based in San Antonio, Texas, got his start at the small market Iowa station and recalled his experiences with the Akai handheld cameras and reel-to-reel recorders being used by KGLO-TV.

“They were looking for a less-expensive way to do news coverage,” said Ostmo. “Film and processing cost a lot and around 1974, they had acquired an Akai VT-150 camera and a half-inch VTR. We would bump the half-inch tape across three-quarter (U-Matic) for editing, but sometimes we would play the half-inch directly to air.”

Ostmo recalled that even with the acquisition of the ENG gear, KGLO-TV continued to capture news events on film.

“The image was so much better with film at that point in time, and they shot the important stuff on film even though there was latency in getting it processed and edited,” he said. “The film processor wasn’t that old when I was there, so I imagine they were still amortizing it. I’m not sure when they went completely to ENG. I left in 1978 and they were still shooting some film.”

Jay Ballard, who began his broadcast engineering career at Boston stations WHDH-TV and WBZ-TV, also recalled the substandard video quality experienced in many early ENG implementations.

“Early ENG quality suffered, as the equipment was not designed for broadcast use, noting in particular the single- or two-tube cameras placed into service at some stations. “Some chief engineers complained that they did not produce ‘broadcast quality’ news footage; however, their objections were overruled by the immediacy permitted by electronic newsgathering means.”

Ballard, who eventually moved to Washington’s NBC O&O, WRC-TV, and then to NBC network operations in New York, recalled that while NBC did experiment with ENG, the network initially shied away from taking it mainstream.

“The big swing to ENG at NBC occurred when the Vietnam War ended in 1975,” he said. (Secretary of State Henry) Kissinger called a press conference and the networks elected not to carry it live. CBS scooped everyone by shuttling the (ENG) tapes they made over to their M Street operation and playing them to that network ahead of everyone else.

Ballard recalled that in the wake of the CBS scoop, other networks quickly began to take ENG’s immediacy much more seriously.

“Shortly thereafter, PCP90 portable cameras and VR-3000 backpack VTRs showed up in Washington. Later, two-piece cameras from Bosch Fernseh and Ikegami were shipped down from New York. NBC spent a ton of money on ENG.”

Ballard noted that even with this initial 1975 push to join the ENG club, the big transition began the following year at the political conventions and the arrival of a three-tube camera with image quality matching that of much larger studio models.

“For NBC, ENG really began with the 1976 Democratic Convention in NYC,” he recalled. “RCA had just announced the TK-76 one-piece camera, and with a portable Sony U-matic recorder, the transition was underway.”

Breaking Away From Film

Despite the immediacy that ENG brought to reporting, as pointed out by Ostmo, image quality wasn’t always that great, and many stations (and networks) still clung to news film. There were also other reasons for retaining film-based operations.

For the networks and some of the larger television stations, craft union jurisdiction quickly became an issue in attempts to transition away from news film.

“Back then, a network film crew consisted of five people — a photographer, a sound person, an electrician to handle the lighting, a producer, and of course, the on-camera talent,” observed Ballard. “It was a mix of IBEW or NABET and IATSE people.”

George Lemaster, who worked at NBC’s WRC-TV in Washington in the mid-to-late 1970s, recalled union jurisdictional issues there.

“At NBC in 1975, news from the field was still mostly done on film,” said Lemaster. “You had union (IATSE) cameramen who were experienced and good at what they did. The ENG crews were made up of NABET people who eventually took control of the event capturing. There were, of course jurisdictional issues. Eventually, some of the IATSE camera operators converted to ENG positions, new to electronics, but they sure knew how to shoot news footage.”

Lemaster explained that this transition was a learning experience for both film camera operators and station engineering personnel-turned-camera-operators, but once the dust settled, the initiative paid off in much faster turnaround of news stories.

Another reason for easing into ENG, rather than flash cutting, was the not inconsequential expense involved in the purchase of color film processing equipment as local stations — following the lead of networks — began to convert from monochrome to full-color operations in the late 1960s and early 70s. A color processor could cost in the tens of thousands (more than $100k today), and these large investments needed to be amortized.

Some stations, however, opted to move completely from film to tape almost overnight. Tulsa’s KOTV was one of these. Lemaster, who worked in the station’s engineering department prior to his move to Washington’s WRC-TV, recalled the Oklahoma station’s transition.

“George Jacobs, the director of engineering at Corinthian Broadcasting, which owned KOTV then, decided to just ‘zero out’ the station’s photochemical budget for one year and use that amount to purchase ENG equipment,” recalled Lemaster. “That was in 1975, just before I went to NBC in Washington.

Jacobs purchased several Sony VO-2850 U-Matic machines, a Sony editor, two Sony DXC-1600 single-tube color cameras and recorders, and a CVS 504 timebase corrector needed to air the video from the (helical scan) VTRs.

“KOTV was a non-union house and this was a ‘cold turkey’ conversion," Lemaster said. "One day we were doing film and the next day, tape. The film editors transitioned over to editing tape.”

Will ENG ever replace news film? Ever is a long time and I’m not that much of a ‘seer,’ but I am not holding my breath yet.

Hugo Bondy, WAGA-TV

Lemaster recalled that in spite of the differences in technology, the changeover went fairly smoothly. However, after some two decades of post-war II television, use of news film was so entrenched, some felt it would never be completely displaced by ENG.

“Will ENG ever replace news film?” Hugo Bondy, chief engineer at Atlanta’s WAGA-TV asked rhetorically in a 1976 SMPTE presentation on ENG. “Ever is a long time and I’m not that much of a ‘seer,’ but I am not holding my breath yet. Film footage will, undoubtedly, shrink. A year ago, I would have said 40%. Now? Who knows, perhaps it will drop to 20%.”

Bondy opined that until a self-contained “camcorder” the size and weight of then-current 16-mm film cameras was developed, “the total reliance on 100% ENG is risky,” explaining that some breaking news events such as a large fire ruled out the laying cables from camera to truck, or getting camera and VTR operators with their heavy equipment close to the scene of action.

Wane Caluger, who spent a large part of his engineering career at Nashville’s WSM-TV (now WSMV), recalled that his station had a slightly different reason for continuing with legacy film operations.

“The guy running the station’s film processor had worked side deals with several area high schools to process their sports footage, so the processor kept going,” said Caluger. “The dual tape/film operation probably went on for four or five years.”

THE ENG Floodgate Opens

Despite poor image quality, jurisdictional issues, prior investments in film technology and general skepticism surrounding wholesale technological switches, there was no turning back, once cameras and recorders were placed in the hands of news crews.

The real genesis of what was to be called “ENG,” may be traced to St. Louis’s KMOX-TV (now KMOV).

The station is regarded as being first in the nation to completely move into the modern era of ENG, doing so at the behest of its then-owner, CBS. The network used the O&O in a pilot project to evaluate technology for expediting the airing of news events. KMOX-TV began its initial experimentation with ENG gear in February 1973, using Akai portable gear, and the results were so gratifying that use of film ended completely in mid-September of the following year.

By that time, KMOX-TV had purchased three Ikegami HL-33 cameras, modified three Chevrolet vans to accommodate microwave gear and provide additional power for lighting gear and an IVC video recorder and support electronics. Crews were also provided with Sony VO-3800 portable U-Matic VTRs. An ENG operation center and editing bays were added at the station. (After editing on the helical scan VTRs, recordings were transferred to 2-inch quad tapes for playback in newscasts.)

In a special report on the KMOX-TV ENG project published in the July 1975 issue of Broadcast Engineering magazine, the station’s news coverage was reported to have increased by 20% since going ENG, and that interest in the initiative had brought inquiries from broadcasters as far away as Japan, Canada and Great Britain. (At the time of the article’s publication, 21% of CBS affiliates had begun to move into ENG, and the number was expected to grow to 37% by the end of 1975.)

With KMOX-TV credited as the first all-ENG operation in the country, it’s then vice president and general manager, Thomas Batista, prophetically stated in the report: “I have a feeling we won’t be the last.”

(The fourth and final installment of this history of electronic newsgathering will trace the impact of emerging technologies and their role in shaping today’s ENG operations and practices.)

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as contributing editor of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a member of the SBE and Life Senior Member of the IEEE.