This Month in Broadcast History: July

First TV commercial aired on July 1, 1941

In 2022 we more or less take it for granted that broadcast television has to exist in a 6MHz-wide chunk of spectrum. This is the way it’s always been—or has it?

Actually, this bandwidth figure goes back 86 years—to the summer of 1936 when the FCC was mulling over a new proposal that had just been delivered in a hearing by the Radio Manufacturers Association, the great granddaddy of today’s Consumer Technology Association. That organization’s Television Committee, comprised of some of the most knowledgeable scientists and television researchers from RCA, GE, the Haseltine Service Corp., Philco, and Farnsworth Television, had drafted the proposal, which began with this “decree” from Philco’s A.F. Murry:

“"The time has arrived for the radio industry to recommend tentative television standards, and to suggest frequency assignments to the Federal Communications Commission… A group of television engineers, representing all of the leading companies active in this field, have met under the banner of RMA, to formulate for you recommended television standards.”

The proposal called for VHF (42-90 MHz) channels “of not less than 6 mc (MHz) for the transmission of high-definition pictures—pictures which experience has shown possess sufficient detail to afford sustaining interest—pictures which will approach the quality of home movies”

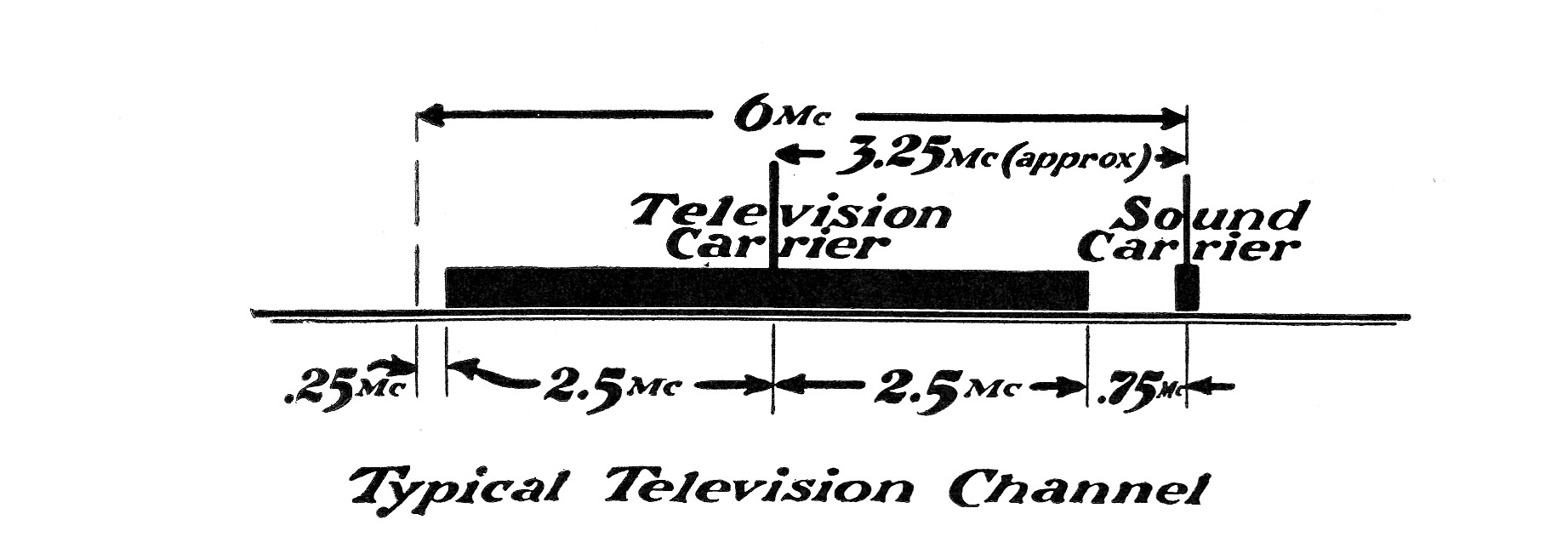

The 6 MHz slots were to be utilized as follows:

- 0.25 MHz (lower guard band)

- 2.5 MHz (lower transmitted sideband)

- 2.50 MHz (upper sideband)

- 0.75 MHz (upper guard band)

- “negligible” spectrum for “sound side bands”

The committee also recommended negative modulation, a 4:3 aspect ratio, 3.25 MHz spacing between sound and picture carriers, a 60 Hz field rate and an 80:20 video-to-sync ratio. The line “standard” was a bit vague, however, with a recommendation for “between 440 and 450 lines per frame” and interlaced scanning.

(The proposal was based on use of then state-of-the-art double-sideband AM video modulation. Development of vestigial sideband transmission technology by RCA’s Wally Poch and Dave Epstein in 1937 would make a significant change in this “nascent” standards proposal. Formulation of a broadcast “standard” acceptable by all industry players would not happen for another five years.)

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

OTHER NEWS FROM TV’S PAST:

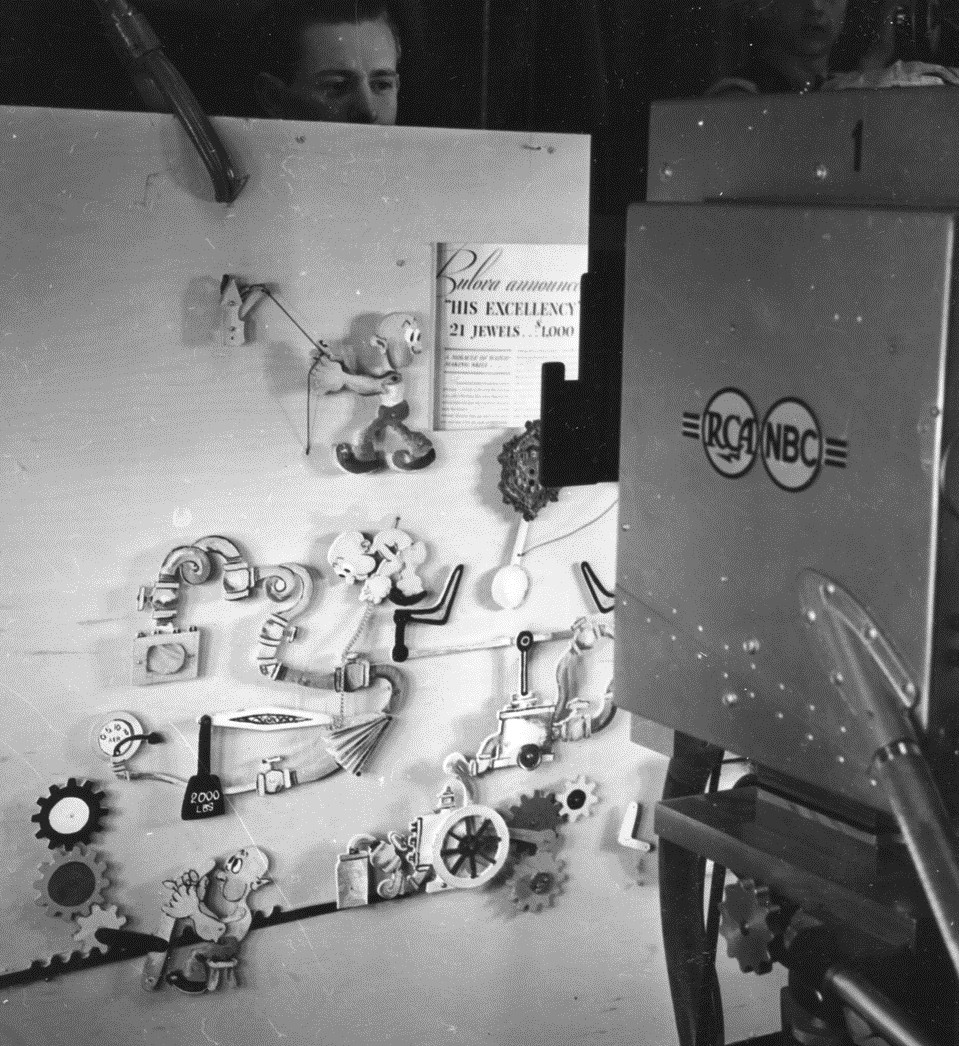

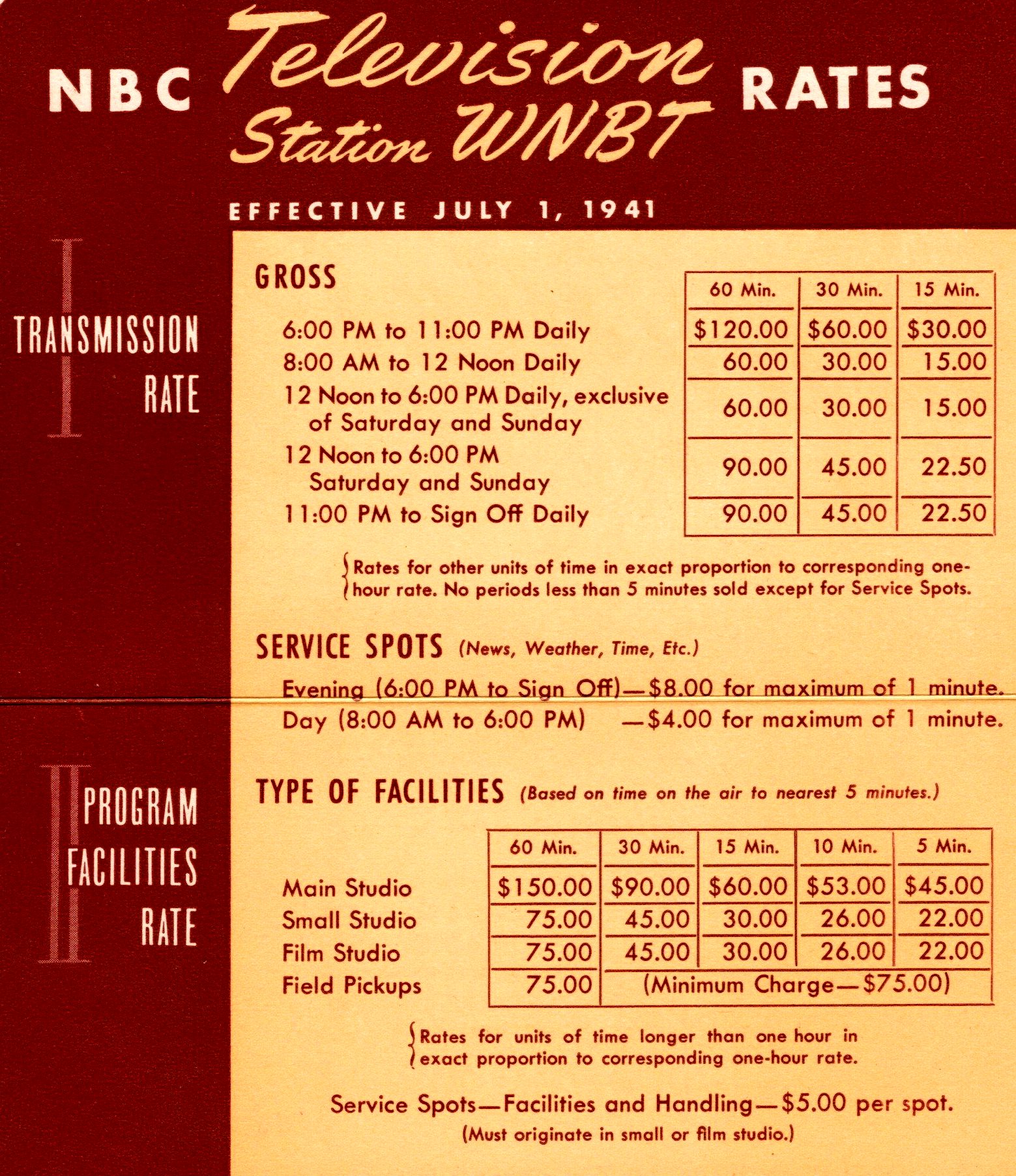

81 Years Ago – July 1, 1941: The first TV commercial aired, following the FCC’s “full commercial authorization” for the handful of stations then on the air. Pioneer NBC station WNBT was ready for the occasion with a rate card (television’s first) and a sponsor, the Bulova Watch Co., which purchased time on the station’s 2:30 p.m. sign-on and 11:00 p.m. sign-off test patterns. (The company reportedly paid NBC $9 for the airing of the commercial.)

July 1 also marked the first time that set owners in and around New York City had a choice of three television stations, with CBS's WCBW, Dumont's W2XWV (experimental license), and NBC's WNBT all now back on the air following TV’s first spectrum repack.)

50 Years Ago – July 1972: Logistics for the acquisition of GE’s broadcast equipment division were being fine-tuned after its sale to Harris Corp. (now GatesAir). GE, along with RCA and DuMont, was a supplier of cameras, transmitters, antennas, and studio gear for the first-generation of U.S.TV stations. WETA-TV, the Virginia-based PBS outlet for the nation’s capital, petitioned the FCC for a “drop-in” VHF Ch. 12 assignment to replace its existing Ch. 26 allocation.

It was hoped that the action—if approved—would set a precedent for other PBS stations operating on (then) less than desirable UHF channels. Critics cited potential for co-and adjacent-channel interference with stations operating in Richmond, Va., Wilmington, Del. and Baltimore.

An industry pundit pegged the odds of Commission approval as about the same as getting rocket scientist Wernher von Braun to join WETA’s engineering staff. (After retirement from NASA, von Braun did relocate to the D.C. area, but took a position with Fairchild Industries in Germantown, Md.; WETA remained on Ch. 26.)

25 Years Ago – July 1997: More than 25 broadcasters pledged to have digital signals on the air by November 1998—just in time for the Christmas buying season. This commitment led to some rather frantic scrambling to identify space for the necessary second transmitting antenna, especially in larger markets.

In New York City the issue was especially acute, as construction of a new “common” mast on the city’s World Trade Center was nixed due to a possible sale of the structure and reluctance by the owner to modify leases. CBS, with an existing lease and backup facility on the Empire State Building, was well positioned to add DTV transmission, but other NYC broadcasters weren’t as fortunate. While admitting it wasn’t the best location due to height and observation deck RF exposure issues, NBC considered installation of a DTV antenna atop its 30 Rockefeller Plaza headquarters.

The move to DTV was also about to impact consumers recording off-air programming. Although JVC and Hitachi were producing consumer digital VCRs, these were intended strictly for recording from Dish and DirecTV satellite services. Sony promised a new digital model with a built-in tuner, the DHR-1000, but the >$4,000 price tag was something of a show stopper for many.

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as editor-in-chief of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a Life Member of the IEEE and the SBE.