Know the Difference Between Backups, Archives

To understand the differences in backup versus archive, one must first realize that the two are not synonymous.

Backing up data is a protective action. Backups are usually a temporary copy of a file, record or data set, which is intended for disaster recovery (DR) or data protection.

Archiving involves the long-term preservation of data. An archive is a permanent copy of the file for the purpose of satisfying data records management or for future, long-term library functions intended for the repurposing or reuse of information at a later date.

Backing up and archiving involve two distinct processes with succinctly different purposes. Today, these terminologies and practices are often used interchangeably. Until recently, some enterprises used their backup copies for both DR and archive purpose, a practice that is risky at best and costly at worst.

How does an organization address these differences? What steps should it take to mitigate risk and reduce cost, while at the same time develop a strategy for file-management that is usable, reliable, and extensible?

GETTING STARTED

First, the organization needs to define its business activity, which in turn helps determine the user needs and accessibility requirements for its data content. The fundamental backup/archive activities for business data compliance will use an approach that differs from those activities that are strictly media-centric in nature. These approaches are determined by many factors, some of which include retention duration, accessibility, the dynamics of the data and much more.

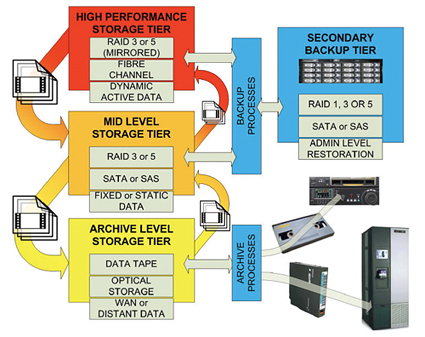

Fig. 1: Tiered Storage Next, one must recognize that simply "backing up to a tape" does not make an archive. The use of data tape brings comparatively higher time and costs associated with it; thus the use of data tape for short-term business data compliance purposes is not as practical as on spinning disks.

With tape, it just takes too long for users to find, examine, recover (or retrieve) needed information—activities better suited for spinning disks used as near-line/near-term storage. However, a broadcaster with a large long-form program library that is accessed only occasionally—as in one episode a day from a library of 500 programs—retaining that content on data tape makes better sense than keeping it on spinning disks.

Where data is placed and onto what storage tier is a management process that should be supported by applications, such as automation or media asset management (MAM). These applications control where the data resides and how long it is at that particular storage location, based upon workflow and usage policies.

When employing tiered storage, only active and dynamic data is kept on primary storage. Fixed or static data, known as persistent (i.e., non-transactional or post-transactional) data, does not belong on primary storage. When persistent data is moved off primary and onto secondary storage, the accessibility to active or dynamic data, which remains on primary storage, is improved.

Tiered storage aids in the management of policy-based storage solutions, which can be deployed on lower cost, medium performance drives. A tiered environment (Fig. 1), like that of hierarchical storage management (HSM)—data that is not accessed for long periods of time—is automatically pushed onto a lower tier where it is offloaded to protected deep storage in an offsite vault.

RETENTION PERIOD

Planning a storage strategy requires determining a data retention period. How long will the organization want to retain the digital content? Will this period increase as time goes on? Retention periods approaching decades can have huge implications in storage management and capacity, demanding a thorough analysis to avoid painting oneself irreversibly into a corner.

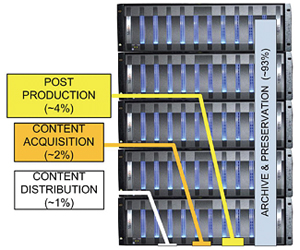

Fig. 2: Storage capacity Finally, consider technology obsolescence. As the age of the media and the period for retention increases, it's likely the transports and the physical media formats will become obsolete. Migrating your data from one archive platform to another that will be readable in the future is the only alternative. Long-term migration strategies should not be done manually; let the archive solution's hardware and software systems manage this process automatically and incrementally.

Organizations should be prepared for an ongoing update of their tape, disk and archive management platforms. By not addressing this at the onset of establishing a media management strategy, the organization will inevitably find itself in a situation experienced by many videotape users—one in which either the tape transports become unusable or the media is unrecoverable.

Finally, it goes without saying that at some point a human must decide the value of the content and weigh it against the cost of keeping it. Some believe the "keep it all forever" perspective is an unrealistic concept given that the growth of data is exponential and unlikely to change as time marches on.

Archive and preservation still commands an overwhelming percentage of the total storage volume as depicted in Fig. 2. With a properly engineered archive and backup strategy, coupled with tiered storage and automated asset management, the enterprise can control this huge volume while achieving a balance between performance and costs all around.

Karl Paulsen is a technologist and consultant to the digital media and entertainment industry. He recently joined Diversified Systems as a senior consulting engineer. A SMPTE Fellow, member of IEEE, SBE Life Member and Certified Professional Broadcast Engineer, he can be contacted atkpaulsen@divsystems.com.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Karl Paulsen recently retired as a CTO and has regularly contributed to TV Tech on topics related to media, networking, workflow, cloud and systemization for the media and entertainment industry. He is a SMPTE Fellow with more than 50 years of engineering and managerial experience in commercial TV and radio broadcasting. For over 25 years he has written on featured topics in TV Tech magazine—penning the magazine’s “Storage and Media Technologies” and “Cloudspotter’s Journal” columns.