The Small-Format HD Quality Puzzle

NEW YORK

By almost every measure, small-format HD cameras should be worse than their larger counterparts. So why do their pictures seem so good?

They are HDTV and do use technologies available 25 years after the first broadcast solid-state camera. But, can a 1/6-inch-format $200 HD camcorder, or even a 1/3-inch-format $5,000 HD camcorder, perform as well as a $25,000-and-up 2/3-inch-format camera?

No. All else being equal, each pixel’s individual sensor on the smaller-format imager (chip converting images into video signals) is smaller. Less area means less dynamic range (contrast ratio).

It also means less sensitivity at any particular f-stop. For sensitivity equivalent to a 2/3-inch-format imager at f/2, a 1/3-inch imager would need to use roughly f/1, but no 1/3-inch-format HD cameras have that large an aperture. Compensating by adding gain yields noisy pictures.

Similarly, 1080-line HD’s 1920 active samples per line represent 100 line pairs per millimeter (lp/mm) on a 2/3-inch-format imager.

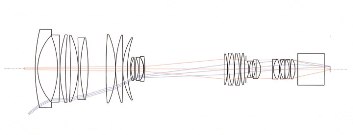

Fig. 1: A typical high-end 2/3-inch-format zoom lens has some three-dozen glass elements divided into four groups.The same resolution on a 1/2-inch-format imager would be 138 lp/mm, 1/3-inch 197, 1/4-inch 245, 1/5-inch 316, and 1/6-inch 379.

A lens for a 1/6-inch format camera, therefore, needs to be almost four times better than a lens for a 2/3-inch camera for similar MTF (modulation-transfer function, indicating contrast delivered at different resolutions). If a 2/3-inch-format lens delivers 80 percent of contrast at 100 lp/mm, a 1/3-inch-format lens would have to deliver 80 percent at 197 lp/mm to match the performance.

Unfortunately, small-format lenses are less expensive, not more. Perhaps the mass manufacture of lenses for consumer HD camcorders helps amortize some optical-design expenses, but it doesn’t account for that great a disparity.

One gray performance area is depth of field. For comparable shots and lighting conditions, a smaller-format camera will offer more depth of field than a larger-format camera. In shooting news, where it might be desirable for everything to be in focus, that could be desirable. In other videography, where it’s desirable to separate the main subject from the background (or even foreground) by means of focus, it’s bad.

FIVE THEORIES

So the question remains. Why do small-format camcorders seem to look so good? Here are five possible answers.

1. You never see Clark Kent and Superman together.

Small-format camcorders are almost invariably demonstrated by themselves; there is no larger-format camcorder shooting the same scene for comparison on a split-screen monitor. If you want to see what you’re missing, arrange for a shootout. Compare image sharpness and texture.

2. Small begets small.

According to theories of 20/20 vision, 1080-line HDTV is optimally viewed at a distance of 3.16 times the height of the picture.

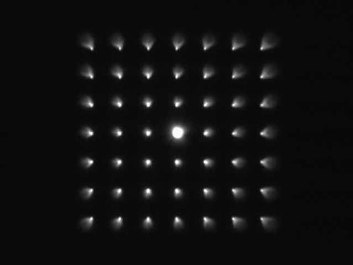

Fig. 2: This image illustrates a lens aberration referred to as a “coma,” in which the dots become less sharp as they move from the center. (Courtesy Mitaka Kohki Co., Ltd.) If you’re checking out the image quality of a camcorder from even a distance of just two feet from a monitor, the 3.16× criterion demands a 16:9-aspect-ratio monitor of more than 15 inches.

A small-format camcorder might be demonstrated on just a 7-inch monitor. And a small monitor might have less than full HD resolution, too.

3. Why, duh.

Fujinon’s popular 2/3-inch format wide-angle lens has a minimum focal length of 4.5 mm. Canon introduced an even wider 4.3 mm 2/3-inch-format zoom at the 2009 NAB Show. So, if Sony’s HVR-V1U HD camcorder has a lens with a wide-end focal length of just 3.9 mm, is that wider still?

No. That camcorder uses a 1/4-inch-format imager. For a shot equivalent to a 2/3-inch-format camera’s, it should use a focal length about two-and-a-half times smaller. So, its 3.9 mm is roughly equivalent to 9.6 mm in a 2/3-inch format, a little tighter than the wide end of a normal lens, not a wide-angle lens.

Wide angles are the toughest aspects of lens design. That’s why wide-angle lenses cost more than normal lenses, even though they have smaller zoom ranges. By eliminating very wide angles, small-format camcorders preserve what quality their imager size allows.

4. Less is more.

Lenses for shoulder-mount 2/3-inch-format cameras and camcorders offer zoom ranges as high as 42 times the wide-end focal length. With the use of tripods and heavy-duty mounts, the zoom ranges go beyond 80×; a special Panavision compound-zoom lens went as high as 300×. Small-format camcorders offer much more limited zoom ranges.

Fig. 1 is a diagram of a typical high-end 2/3-inch-format zoom lens. It has some three-dozen glass elements divided into four groups.

The group at the far left focuses the lens. The next group, the variator, changes magnification when zooming. The third group, the compensator, maintains focus during zooming, using highly complex motion.

The last group relays the image created by the other groups to the camera’s imager. It’s possible to use the same lens design for both 2/3-inch- and 1/2-inch-format cameras, changing only the relay optics.

Unfortunately, a typical built-in-lens small-format camcorder has room for neither three dozen optical elements nor the motion of long-range-zoom variator and compensator groups. So, different, less-high-quality optical designs are used.

5. It’s good to be well centered.

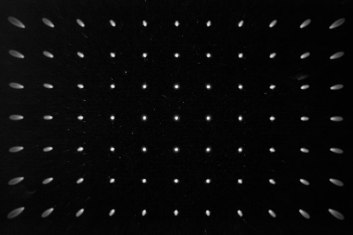

Fig. 3: This image illustrates a lens aberration called “astigmatism,” in this case, proportional to the square of “image height.” (Courtesy Paul van Walree)

Some small-format camcorders allow use of larger-format lenses without optical compensation. In that case, the imager makes use of only the central portion of the lens. If a 2/3-inch-format zoom lens is set for a 9-mm focal length, a 1/3-inch imager looking through that lens will see the 2/3-inch-format equivalent of about an 18-mm lens.

The bad news is the loss of even more of the wide angle. But there is good news, too.

Some lens aberrations are related to something called “image height,” actually the distance from the central lens axis. Fig. 2, courtesy of Mitaka Kohki Co., Ltd., illustrates one of those, called coma. The dots become less sharp as they move from the center. But a small-format camera would cram more resolution into the central area, and the aberration would not change.

Fig. 3, however, courtesy of Paul van Walree, shows a different aberration, called astigmatism, in this case proportional to the square of “image height.” By using only the central portion of the lens field, in this case a small-format imager would actually eliminate the worst of the aberration.

Otherwise, in imager formats, bigger is better.

Originally published in the June 10, 2009 issue of TV Technology.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.