Do “Frankens” Really Fit Into the Radio Ecosystem?

We conclude our three-part series, as the FCC opens a new NPRM

(Editor's note: This article originally appeared in Radio World.)

The FCC has opened a notice of proposed rulemaking intended to decide whether FM6 stations have a permanent place in the U.S. broadcast landscape.

Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel may have indicated which way she is leaning on the issue when she previewed the NPRM by saying the commission would be “asking about preserving established local programming for radio audiences.”

James O’Neal wrote about the new wave of FM6 stations in our March 30 and May 11 issues. He concludes the series here; this article was prepared prior to the release of the actual NPRM, summarized here and which you can read here.

Although many thought “Franken FMs” would quickly fade from the scene when the FCC pulled the plug on the last of the analog Ch. 6 LPTV operations last summer, this has not been the case.

By now several of the new wave of ATSC 3.0 digital TV/87.75 MHz FM audio broadcasters are going strong, enabled via some 21st century RF filtering technology and FCC-issued STAs, of which 13 have been issued.

The original (analog Ch. 6 video/FM audio carrier) Frankens certainly drew their share of comments from the radio broadcast community, and now this new wave of hybrid DTV/analog FM operations is coming under scrutiny, with some sharply divided opinions.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

We begin with comments from the implementer of the first of these “second-gen” Frankens.

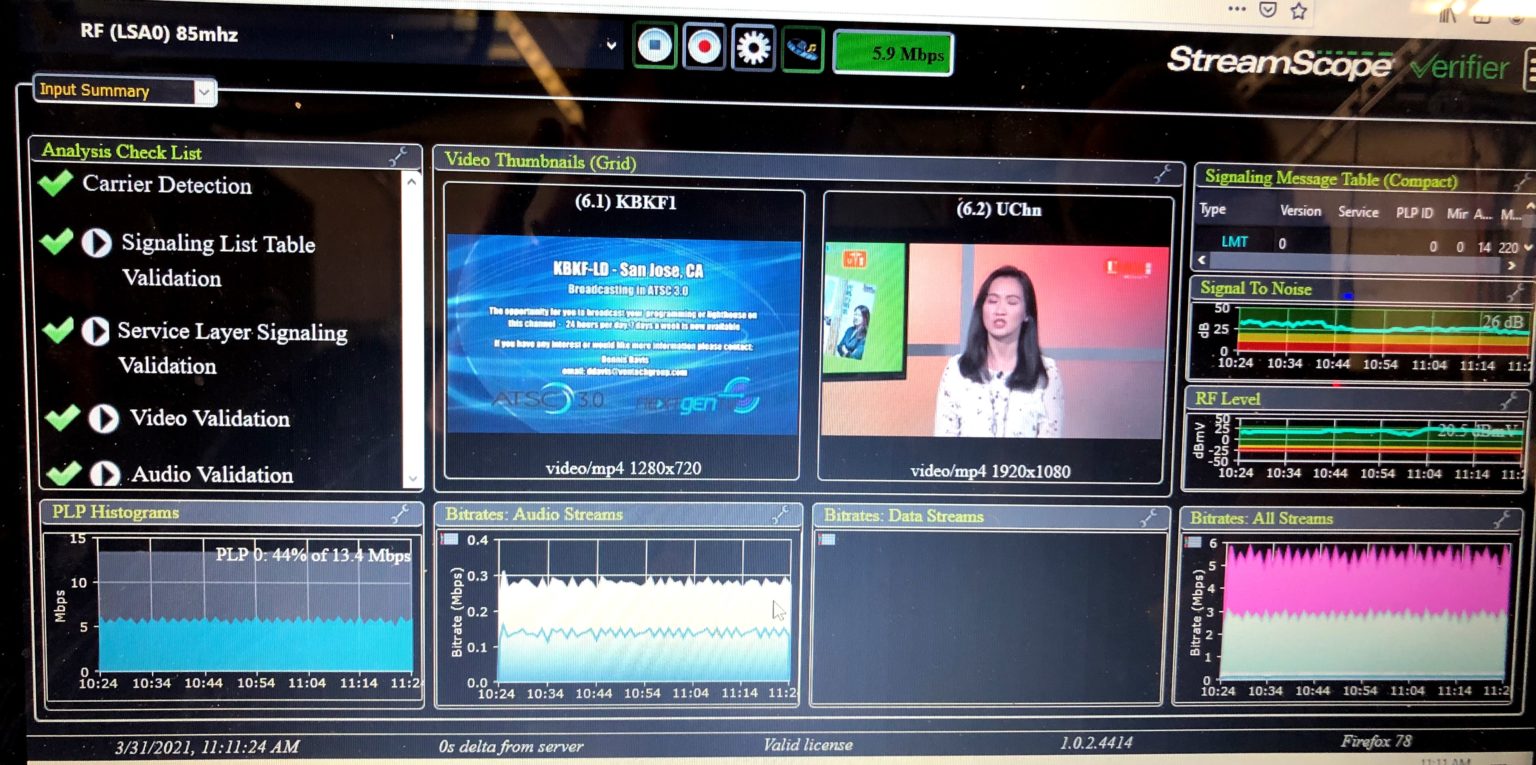

Possibly the biggest proponent of the hybrid DTV/FM technology is Paul Koplin, CEO of Venture Technologies, which owns KBKF(LD), a San Jose, Calif. low-power Ch. 6 TV station that switched on its ATSC 3.0 DTV/analog FM operation in March of 2021.

“When we converted to digital [TV broadcasting], we thought about the best way to achieve a hybrid model and to the FCC, this works well,” said Koplin. There’s no interference between the two services per FCC rules.”

Koplin observed that VHF TV spectrum — especially the low-band Channels 2 through 6 — has become “low-rent” real estate due to the ever-increasing amount of manmade noise in that region, and says these new Frankens are able to wring some utility out of this region.

“This spectrum was a lemon and [with the hybrid broadcasting] we made it into lemonade,” said Koplin. “It’s a win-win solution.”

He noted that the initial STA on which KBKF was operating had been renewed, and looked forward to the day when the FCC officially recognized Ch. 6 hybrid broadcasting by codifying rules and regulations for it. In doing so, this would become an additional revenue stream for the commission.

“The FCC is getting additional revenue from what we’re doing as we’re paying supplemental fees,” he said, adding that “there’s no technical reason for anyone to oppose this. We’ve had no technical issues, and there’ve been no interference complaints. No major radio groups are opposing this sort of operation, only NPR. They don’t want anyone to the left of their dial position.” [In fact the National Association of Broadcasters and other major broadcast groups have filed vocal opposition.]

Koplin expects other Ch. 6 licensee to follow his lead, and perhaps even build on it by providing services that go beyond radio and television.

“It’s one step at a time right now,” he said. “We’re the first in the country to provide this service. The Channel 6 supplemental use case we’ve established is a pathway for other stations to use their spectrum for even more innovative services.”

“I just wish I’d thought of it!” remarked Chuck Conrad, the owner and general manager of Tyler-Longview, Texas radio stations KZQX(FM), KDOK(AM) and KYZX, when asked for his take on the Franken resurgence.

“If nothing else, I admire the ingenuity of whoever first implemented it. I’m sure a lot of other broadcasters will disagree with me because the industry doesn’t like additional competition. Why would they? If people are listening to the Franken FMs, it means they are not listening to their station. It’s a simple as that.”

A lot of objections past and present stem from potential interference to existing broadcast operations, and this concern is registered in the STAs under which the new Frankens are operating. Conrad was asked about this possible downside.

“When these Franken FM stations were riding along with an analog Channel 6 TV signal, the reports of interference to the lower end of the FM band were few and far between,” he said. “As far as I know, all were resolved. Some of those stations became quite successful. I see no reason to not give them the blessing of the commission.”

Aaron Read, the IT and engineering director at Rhode Island Public Radio, has a different opinion. Read, speaking only for himself and not for his employer, says the technology that’s enabling these new hybrid broadcasters might be valid, but the application of it is not.

“Technology is a tool, and tools are value-neutral,” said Read. “It’s how you use the tool that matters. And that’s why I have a problem with this use of the tech. It has nothing whatsoever to do with providing any television service, much less an improved television service. It’s merely an end-run around all the existing rules for creating FM radio stations. And worse, it bypasses most of the technical rules that protect FM radio stations from interfering with each other, and it also bypasses the FCC fee structure that the agency depends on for its operating revenue.”

Dave Kolesar, a senior broadcast engineer at Washington’s WTOP and Federal News Network, shares the belief that the first- and second-gen Frankens are a somewhat misdirected application of technology for creating an FM radio service.

Kolesar, also speaking for himself and not on behalf of his employer, stated: “I think the evidence for this is based upon the fact that in the analog days such operations were generally not marketed to the public as television stations, and so 6 MHz of RF spectrum was effectively allocated for just one analog FM signal.

“In an ideal world,” he said, “I’d like to see 87.7 and 87.9 opened to commercial FM service if there are no TV stations on Channel 6 in the area. In that ideal world, a Ch. 6 TV station could surrender its TV license and apply for an FM license on that channel.”

He added that he did not favor a downwards expansion of the current FM band to occupy all of the TV Ch. 6 region, as there are no readily available receivers that cover this. He also feels that any new radio broadcasting spectrum allocations should be for digital services.

[Related: “Letter: We Don’t Need This Franken“]

Given the apparently popularity of these new DTV/analog FM stations, the FCC seems obliged to make a binding decision about them, rather than continue to renew STAs.

“I think if this concept is allowed to stand in any form,” Aaron Read said, “it’ll be inevitable that the FCC will be ‘forced’ to legitimize them, and also that you’ll see greater proliferation of LPTV-6s operating as ‘Franken FMs,’” said Read. “I put ‘forced’ in quotes since they are, of course, ‘forcing’ themselves by not blocking this service from existing in the first place.

“There has always been a strong ‘pro-TV at the expense of FM’ bias written into the Part 73 rules in the Code of Federal Regulations,” he continued. “But more than that, there literally is no regulatory structure in place to manage interference from these ‘Franken FMs.’”

He said regulation 47 CFR 73.525 has many rules and engineering specs, but they’re all in reference to the NTSC television standard, which no longer exists.

“There [are] no rules for dealing with ATSC. How is anyone supposed to know when prohibited interference is legally occurring? And to say that these TV stations ‘aren’t allowed to interfere’ with FM is wildly disingenuous. How are FM stations supposed to prove that interference exists? By listener complaints? Does the FCC seriously expect your average listener to even realize when they’re hearing interference, much less recognize what the interference is, and know enough to contact the FM radio station about it?

“At a bare minimum, if the FCC is going to allow this terrible idea to proceed, a complete rewrite of 47 CFR 73.525 is an absolute necessity so that FM stations have something to fall back on.”

National Public Radio long been critical of Frankens due to the proximity of their 87.75 MHz operating frequency to that of non-commercial broadcast allocations, and it has filed objections about their operation.

Asked about its stance on this second wave of Frankens, Marta McLellan Ross, the organization’s vice president of government and external affairs responded: “NPR continues to monitor the use of STAs and whether interference occurs as a result of their use. We remain vigilant for any actions that would result in interference with our member stations’ ability to reach their audiences.”

[The FCC said in the new NPRM that it wants comments on an NPR proposal that the commission should license additional NCE FM radio stations on 82–88 MHz in areas where Channel 6 LPTV and full-power stations are not operating.]

[Related: “NPR Hopes Franken FM Resolution Includes New NCE Stations“]

As for the FCC’s position, a commission spokesperson provided this statement in May, prior to release of the NPRM:

“The provision of so-called ‘FM6 services’ has been going on for over a decade. Today, there are actually fewer stations that are operating in this manner. We have permitted these stations to continue operating pursuant to STAs, as we evaluate the technical, legal and policy issues surrounding these services.

“In mid-2021, with the LPTV digital transition deadline fast approaching, the Media Bureau began granting six-month digital engineering STAs to some of the previous analog FM6 stations,” the spokesperson continued.

“This was an effort to minimize consumer disruption by allowing these previous analog FM6 stations to continue their FM6 operations after they converted to digital. To date, only 13 of the original analog FM6 stations have been granted these digital engineering STAs. The previous analog FM6 stations were required to convert to ATSC 3.0 digital operations and could continue FM6 operations separately through the six-month digital engineering STA. These STAs were granted with several conditions to ensure that there would be no harmful interference to other users and to also ensure that the station fulfilled its obligation to provide TV programming to its TV audience.”

The spokesperson said stations are required to report every three months on any interference complaints they had received, and that none of the stations has reported interference to date. Several of the STAs have been renewed for an additional six months since their initial grants.

Just as with about everything else these days, there seems to be no middle ground concerning these hybrid digital TV/analog FM operations.

It would seem that the appeal to operators is biased on the radio side due to the potential ad revenue, a decline in off-air TV viewers, the relative scarcity of ATSC 3.0 receivers and the limited availability of LPTV stations on cable systems.

However, this could change, making television broadcasting activities more viable. Also, given the continuing shift away from analog broadcasting, perhaps it’s just a matter of time before Major Armstrong’s wonderful, 90-year-old, interference-free broadcasting modality will be relegated to the history books; if so, even these “second-gen” Frankens will have no relevance and there will no longer be an issue. Only time will tell.

Meanwhile, these hybrid DTV/FM stations continue to attract niche audiences and generate operating revenues for their owners or operators.

[Related: Radio World Editor in Chief Paul McLane celebrates James O’Neal]

Comment on this or any article. Email radioworld@futurenet.com with “Letter to the Editor” in the subject line.