FCC Forum Highlights Closed Captioning Issues

Shift in consumption of video has industry asking whether current requirements are enough

WASHINGTON —By 2010 standards, it was probably hard to imagine just how ubiquitous online video consumption would be in 2021.

Eleven years ago the U.S. passed the Communications and Video Accessibility Act (CVAA), a piece of legislation that gave the Federal Communications Commission the authority to regulate closed captioning for television programs that were broadcast over the air (as well as U.S.-aired programs that were then streamed online).

Here in 2021, however, a growing amount of online video programming viewed by consumers does not fall under the FCC’s regulatory captioning authority at all — an issue that continues to raise implications for consumers who have hearing challenges.

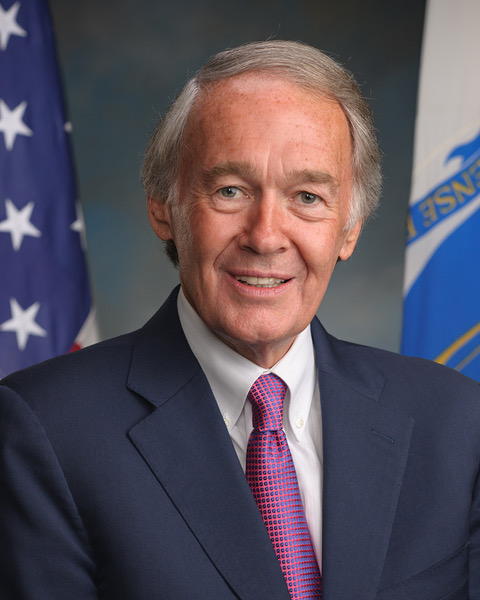

The realities and challenges facing the media industry as it tries to navigate this arena were the subject of an online forum on Dec. 2, and hosted by the commission’s Media Bureau and the Consumer and Governmental Affairs Bureau. FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel, Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), video programming providers from Netflix, NBCUniversal and Amazon as well as industry stakeholders and advocacy groups discussed developments in closed captioning and the real-world challenges at hand.

While the FCC has clearly defined rules on what video must be captioned (see sidebar), a significant portion of online-only videos and programs fall outside the commission’s existing closed captioning rules.

So how must the industry evolve when it comes to closed captioning? And how should the FCC’s policies and laws change to keep pace with changes as the video marketplace changes?

Ready to Talk

“[The FCC heard] that it would be helpful to bring key stakeholders together to explore the state of closed captioning availability for online video programming and discuss ways to enhance accessibility,” Rosenworcel said in kicking off the event. “And here we are.”

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

While the goal of the original CVAA legislation was clear—to help ensure that the deaf or hard of hearing can enjoy the same entertainment and programming as other Americans—more needs to be done, said Sen. Markey.

“The coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the challenges too many individuals still face in obtaining equal access,” Markey said in a series of recorded remarks. “In particular, it is clear that we must expand access to closed captioning in the online video and streaming marketplace, as well as [promote] consistency in captioning content across video platforms.

“As the world has moved from a television and cable model to an online model,” he said, “we have to move all of those technologies that provide accessibility… over there as well.”

The two-and-a-half-hour session was split into two panels—the first looked at the technical and business issues surrounding closed captioning and ways to enhance the availability of online closed captioning. The second panel examined the scope of the commission’s authority and ways to fill the gaps in current online closed captioning requirements.

So what, in short, should the industry be doing to improve captioning?

Some forward-thinking work is already being done by online programming providers who are voluntarily captioning their programming, even without federal rules mandating such steps.

“At Netflix… we believe that art can help build empathy and understanding and reduce prejudice as a window towards a more inclusive society,” said Heather Dowdy, director of accessibility for Netflix. “We understand that accessibility is just as important as aesthetics and speed and stability,” she said, explaining that Netflix’s viewing capabilities includes assistive listening system support, brightness controls, keyboard shortcuts, compatibility with screen readers and voice commands. The company is also expanding its catalog of titles with subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing as well as audio description for people with vision disabilities, she said.

Other video providers like Amazon Prime Video are working with its in-house studio and third-party content providers to ensure the availability of closed captions on programming. The company is also investing in automated sensor technology to detect incorrect or defective closed captions like spelling mistakes, reading speed violations and out-of-sync captions.

Broadcast Legacy Not Conducive to Streaming

While the prevalence of closed captioning in the marketplace may be boosted by the big programming providers, a number of technical hang-ups remain.

“The technical aspects of captioning quality were not improving… and the technology has not advanced much since the 1980s, from the consumer’s perspective,” said Dr. Christian Vogler, director of the technology access program at Gallaudet University. Dr. Vogler is currently leading a five-year project that is researching how the usability of closed captions can be improved.

According to Vogler, there are a whole host of challenges that consumers continue to face in accessing and viewing online closed captioning. One is the lack of consistently high-quality captions, which can vary greatly depending on where the captioning is coming from, he said. Another challenge: closed captioning workflows in existence today are still very much tied to broadcast television, he said, making the appearance of closed captions appear less than ideal on a computer or mobile device.

Technology companies are offering some suggestions. Google has created a live captioning tool that allows a viewer to see captioning in real time. “It is no replacement for human-generated captions but it gives someone the ability to experience what is happening in real time so they can access the communication,” said KR Liu, head of brand accessibility at Google.

The company also has created tools within YouTube that allow a video creator to integrate captioning directly into their content. “More and more, that is becoming a standard and important practice—that we educate our creators on incorporating [captioning],” she said. “We are seeing captioning being ‘burned in’ to make sure that [these] captions cannot be turned on and off. There are ways that we can come together and utilize each other's technologies and platforms to better provide access for everyone.”

For Daniel Kocmarek, general manager of global video supply chain and content operations for Prime Video, the most important first step is to decide that accessibility is a priority for an organization. For example, license agreements between Prime Video and third-party content providers require that the third parties deliver closed captions in the original voice language of the content.

Customized Captioning

Members of the panel also discussed how to ensure that captions on streaming videos can be customized based on the device being used. Step one: ensure that caption settings are easy to find. Step two: provide a way for viewers to customize how captions look. Step three: advocate and adopt standard file formats.

“[We] want to contribute to industry-standard documentation and content that would help engineers navigate scenarios during development and testing,” Kocmarek said.

For Dr. Vogler, the time has also come to establish a common testing protocol in order to verify that captions are in compliance. “I would encourage anyone and everyone to be part of implementing something like that so we can see such a reality,” he said.

And what about the best solution for creating captions in the first place?

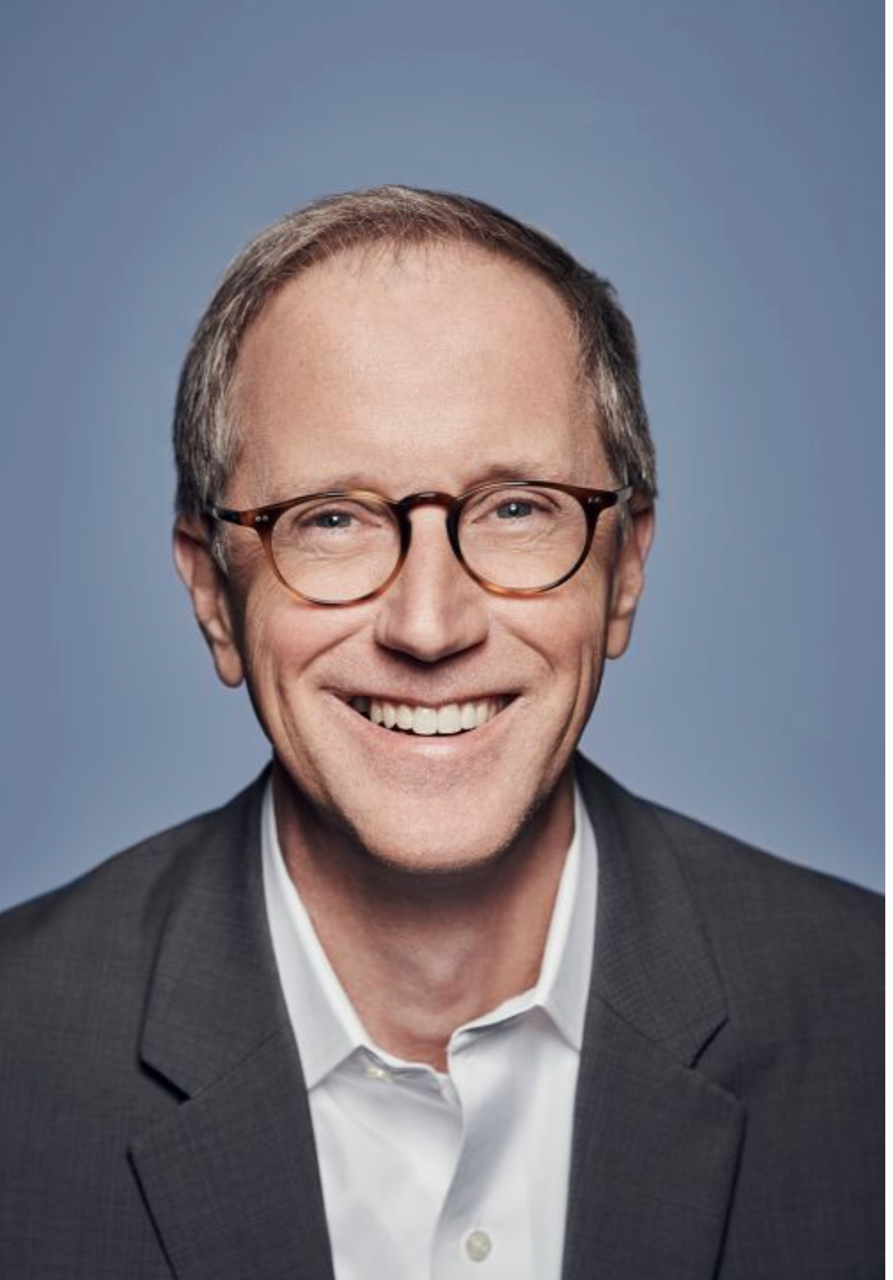

“There is, of course, the human creation of closed captioning, but in terms of scale I think the most promising scale is ASR,” or automated speech recognition, said Jim Denney, executive vice president and chief product officer at NBCUniversal. ASR can be an effective tool to create captions that do not already exist and the technology has the benefit of aligning with other applications in the industry. “I think that ASR is one of our most promising tools in getting closed captioning into short-form clips,” he said.

And what about that vast, uncaptioned landscape of consumer-generated videos? What tools might be developed to caption those videos? Some platforms already do an excellent job at generating closed captioning, Dr. Vogler said, pointing to YouTube and the platform’s support for generating closed captioning.

“YouTube is a quintessential example of making it easy to make closed captioning for user-generated content,” he said. “TikTok does a similar thing in terms of making it easy for users to generate the caption of their own content.” Unfortunately, however, there is no standardization as of yet, he added.

What the industry needs is two-fold, he said. One, support for ASR captioning and the ability to modify and improve auto-generated captioning online. And two, editing tools that can support closed captioning implementations. “Often consumers have to either do a search for a third-party tool in order to add captions to that video, or pay for an expensive upgrade to get access to that,” Dr. Vogler said.

Captioning also needs to be encouraged to be a part of the creative process, said Google’s Liu.

“The more that we can help creators … [provide] captioning to their content, the more that is visible, the more we can encourage other platforms to provide those tools to help make captioning available for creators—that is what is important here,” she said. “Captioning very much is a part of communication and connecting with people. [A]llowing people to experience that content is really important.”

The Regulatory View

The FCC’S role in regulating the marketplace was the focus of the second panel discussion. According to Blake Reid, professor at the Technology Law & Policy Clinic at the University of Colorado Law School, the captioning requirements for media that the CVAA set up in 2010 look nothing like the media marketplace of today.

“We live in this world where the FCC’s captioning rules are divided between the legacy media… and a separate set of rules for programming that is delivered via internet protocol that has been on one of those legacy media channels,” he said.

“We don't live in that world anymore,” he said. “We now live in a world where legacy TV and internet-delivered video have converged. From the perspective of consumers, they are now one in the same.”

It’s time for the commission to recognize the reality that consumers and the industry already see—that online video distribution services are “television” and that it is time to extend the mandate for closed captions to online video as well, he said.

Others said that the commission needs more statutory authority from Congress before it can contemplate requiring online-only programmers to caption online videos. “I know there is a lot of captioning going on in that area voluntarily, or in response to market forces or legal cases, but as far as the FCC being able to require it, it doesn't seem like they have plain and clear authority under the framework right now,” said Larry Walke, associate general counsel for the National Association of Broadcasters.

The Market Responds

So how can the commission support consumer access to captioning of online programming that’s not required to be captioned?

Fortunately, more and more outlets are captioning on their own because it’s the right thing to do, Walke said. As far as what the FCC can do specifically? First, the FCC must work to educate and encourage online platforms to voluntarily caption more of their content. Secondly, the FCC should be careful to do no harm. “We would caution the FCC against adopting any rules that might hinder innovation or [thwart new] technologies that could make it more efficient to caption programming online.”

Added Jacqueline Clary, vice president and associate counsel with NCTA, the best rule for the FCC to follow is to facilitate conversations and solutions between the industry and advocates. “To the extent the FCC can encourage voluntary industry efforts on evolving accessibility solutions like ASR, it could be really helpful,” she said.

However, Zainab Alkebsi, policy counsel with the National Association of the Deaf, believes that education and conversation is critical but not sufficient in itself. The commission should coordinate with Congress to help shape new legislation in this area so that the goal of 100% captioning of video programs can be met.

“While multistakeholders are important and innovation is important, it needs to come with the legal obligations that only the FCC can bring,” Reid said. “Because we are talking about the civil rights of people with disabilities, it is not optional. It is not aspirational. It is something that is necessary to ensure an equitable society. That is what we are striving for.”

The panel concluded with discussions on whether the FCC should expand captioning requirements for video clips, whether or not additional regulations would help increase the availability of online closed captioning and what role the marketplace will play in encouraging more captioning from reluctant captioners.

“If an online video platform wants to win viewers and advertisers and subscribers, they are going to need to compete with other providers who are providing captions,” the NAB’s Walke said. “Beyond the competitive mandate, many of them I assume are doing it because it is the right thing to do.”

SIDEBAR

To Caption or Not to Caption — That is the Question

The Federal Communications Commission has issued specific rules on what must be captioned—whether it’s by a broadcaster or a third-party video distributor for full-length videos, clips or video montages. As part of Title 47, Part 79.4 in the code of Federal Regulations, the Communications and Video Accessibility Act of 2010 made it a requirement that full-length video programming that has already been shown on television with captioning in the U.S. must be captioned when it is redelivered online.

In effect, this means that caption rules do not apply to full-length programming that has only ever been streamed online. There are also no captioning rules for online consumer-generated programming either unless, of course, it has previously been shown on TV with captions.

When it comes to video clips—meaning a segment of an otherwise full-length video program—the requirements are more nuanced, according to Suzy Rosen Singleton, chief of the Consumer and Governmental Affairs Bureau's Disability Rights Office.

Video clips of captioned full-length programming must be captioned if posted on the video programming distributor’s own website or app. But this means there are no FCC captioning rules in place for video clips posted on third-party websites or apps.

“Just to provide a concrete example of this, if you were watching something on CNN and that clip is subsequently shown on CNN’s website it must be captioned, but not if it is being shown on a third-party website like YouTube, for example,” Rosen Singleton said.

There are also grace periods for recaptioning certain live and near-live programming.

The commission also has rules on the accessibility of captions—meaning how easy it is for a consumer to see the words on screen. “[This is really important because] there is really no use in having captions if captions are not accessible, or if they are too small to be readable, or if the color does not work for you,” Rosen Singleton said.

The FCC also has rules on activating and customizing captioning. According to Rosen Singleton, covered providers must include a simple and easy-to-use method for activating the captioning, be it a button or icon. In addition, FCC rules require there to be customizable captioning features such as character color, character opacity, character size and captioning window color, among other things.

A complete list of the closed captioning requirements for video programming delivered over IP can be found here and a regulatory overview of IP requirements is available here.

Susan Ashworth is the former editor of TV Technology. In addition to her work covering the broadcast television industry, she has served as editor of two housing finance magazines and written about topics as varied as education, radio, chess, music and sports. Outside of her life as a writer, she recently served as president of a local nonprofit organization supporting girls in baseball.