Game On: Bringing eSports to the Masses

NEW YORK — Video games are not just played by teenagers these days, and there are now professional gamers who regularly take part in eSports competitions around the world. According to research from Newzoo, a marketing tracking company, eSports was on track to have an audience of more than 427 million people by 2019, up from 226 million in 2015.

The global eSports market, which began as PC and video game console-based competitions, is currently expanding to mobile. A Newzoo report from April 2017 found that already 42 percent of the gaming market was on mobile devices, and it is slated to increase by more than 50 percent by 2020.

As a sport there are still challenges in providing a compelling viewing experience to the audiences watching not only on TVs but on PCs, tablets and increasingly mobile devices as well. To overcome these challenges the eSports industry has been taking cues from how past sports have been delivered to the masses. This is already apparent with ELEAGUE, the professional eSports league that began broadcasting in 2016 on TBS.

FOLLOWING THE ‘STICK AND BALL’ MODEL

“We’re taking what we’ve learned from traditional ‘stick and ball’ sports on how to produce this,” said Craig Barry, executive vice president and CCO of Atlanta-based Turner Sports. “First, it is important to have those with a passion working on it.”

In this regard eSports is just sports with an extra letter in front.

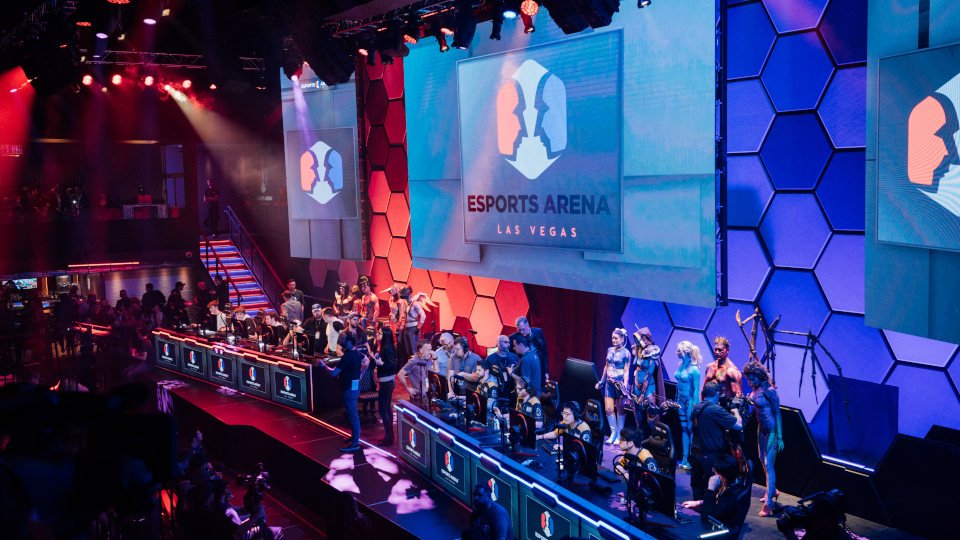

“All of the innovation that we’ve seen used for basketball or baseball as just two examples, is now being utilized with eSports,” said Stuart Lipson, executive director of the Esports Ad Bureau in New York. “This has been about extending it to a wider audience, complete with the arena like experience.”

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

[Read: 2018 Guide To Sports Production Is Now Available]

What sets eSports apart from more traditional sporting events is that the audience is just as likely to be watching on a mobile device as their living room TV.

“This is a young audience that watches it on multiple platforms, just as it is a sport that uses multiple platforms,” Lipson said. “The downside is that this makes it more complex on the production side. We have to ensure that we can provide the same experience to the viewer, whether they are actually seeing it at Madison Square Garden on their handset on the other side of the world.”

IN YOUR FACE

eSports differ from the traditional team-based sports — notably football, basketball and baseball — in that the players aren’t technically “in the arena,” at least not in a physical sense. This is different even from auto racing where the drivers are on the course, albeit in vehicles. The closest comparison may be to chess where the players are looking at the same competition “field” as the audience.

The way this is being presented is steadily evolving suggested Mike Vorhaus, president of Magid Advisors, a Los Angeles new media firm. “Currently this involves capturing action on multiple screens that can include having the gameplay heavily emphasized, where the player/competitor is emphasized less so than in other sports,” he said.

However, individual eSports athletes/competitors are making a name for themselves and thus getting their close-up.

“Normally the athletes always have a camera on their face, in order to catch any emotions that come from the gameplay — and there is a LOT of emotion — this is often placed picture-in-picture with what they are doing in the ‘virtual world’ or-in game,” said Reggie McKim, video game analyst at SuperData Research. “This allows the viewer to tie an action in game, to the emotion elicited, i.e. something happens in game and the athlete shouts and high-fives his teammates out of game vs. something happens in game and the athlete shouts and puts his face in his hands out of game.”

In most situations this is quite easy for the production team to cater to both experienced viewers who have played the game and inexperienced viewers who may not play games.

“The experienced player already knows what has happened and whether it is good or bad, because they have most likely experienced a similar action and response," said McKim. “The inexperienced can glean the same information by watching the athlete’s emotion. Catering to both viewer types is one of the biggest hurdles for any eSports production/broadcast, especially something that will be broadcast on television to the general public.”

Another way that eSports is evolving when it comes to production is how it is taking cues from the way the NBA puts the spotlight on key star players.

“You can find the same thing happening in the more professional and established eSports; more tournaments have a pre/post- show, post-game interviews with the MVP, fan meet-up opportunities, personable/out-of-game produced shorts,” added McKim. “Presenting all of the information of the game state in an easily digestible way tends to be the biggest problem for any production team, outside of technical hiccups.”

DELIVERING THE ACTION

Because it is still a growing industry — and lags behind true billion dollar sports such as professional basketball or football — eSports hasn’t gone prime time. However, broadcasters like Turner are treating it like they would other sporting events.

“We approach it like any other sport,” said Turner’s Barry. “The back-end infrastructure is super important. That is first and foremost the most important part of this.”

ELEAGUE has standardized the gaming hardware the competitors use — typically Dell monitors and computers from Alienware, a Dell-owned gaming PC manufacturer.

“This is no different from how the cameras are calibrated for a stick and ball sport, and sent to a standard truck,” Barry said. “What is different is that we need two different production teams. There is an observer feed that is cutting the gameplay; and there is the show feed that is capturing the players, spectators and action in the arenas.”

In most situations Barry said the observers are just watching the on-screen competition and cutting from virtual cameras so that the audience sees essentially the same thing as the player. This feed is then intercut with the show feed.

“In most matches the observer feed is on 75 percent of the time,” said Barry. “These need to come together to deliver the experience, and then these are processed together and sent out on that very wide pipe.”

The biggest challenges relating to eSports broadcasting primarily stem from the intensive hardware use required to capture, compile, and transmit feeds from several computers involved in the competition.

“The technology exists but with any production, the introduction of more potential points of failure adds to the necessary quality-assurance workload,” said Justin Dellario, head of eSports programs for online video game channel Twitch, a live streaming video platform and subsidiary of Amazon. “Another challenge worth mentioning, which can also be seen as a positive differentiator for the content type, is the sheer number of camera feeds involved in any broadcast.”

One example is the recent “Overwatch” competitions, a team-based multiplayer first-person shooter video game that can require a dozen feeds for the gameplay video and another dozen for the audio, before compiling and transmission just to capture the game feed for every competitor.

“This is often combined with a ‘player’ showing the player’s reactions in real time along with gameplay, adding 12 more feeds which have to be properly synchronized,” Dellario said. “In a live setting, these are on top of the feeds capturing the physical location, broadcast talent, and any other special views the production wishes to use to provide their total desired viewing experience for the consumer.”

Another important aspect of eSports broadcasts is the in-game spectator tools, which truly differentiate it from more traditional sporting events. These allow customization not only by those playing but on the production side and even by the viewer at home.

“The overall quality of broadcast resulting from presenting a gaming competition is heavily reliant on how deep of an in-game spectator tool set that the game developer has produced,” said Dellario. “In-game spectator tools are sometimes the only enabler the production teams have to zoom around the in-game environment and quickly switch between players views, birds-eye views, and present in-game stats in real time. This must also be combined with specialized graphics and overlays tailored to each individual game’s UI and tracking needs, adding additional workload to all graphics and UX design needs.”

DIFFERENT PLATFORMS, DIFFERENT EXPERIENCES

While Twitch is just one of the ways that eSports fans are watching the games, streaming media continues to play a key role.

“Twitch has been extremely effective in providing the gaming experience to those who aren’t typically sitting in front of the big TV in the living room,” said Gayle Dickie, CEO of Los Angeles-based Gamer World News Entertainment, Inc. (CWNe), a 24/7 go-to source for eSports and gamer news. “Video streaming services are becoming the go-to place for these competitions.”

The challenge today is trying to provide that everyone — from the viewer of the action on a large screen TV to a mobile handset — gets a similar experience, and that the audience remotely can see the action the same way as the player. While it is true that live sports in the arena, stadium or other venue differs from what the audience sees at home, the goal of eSports is to ensure that the playing field — literal and figurative — is as close to the same for everyone.

“One challenge is that players are spending thousands of dollars on computers with the latest graphics engines,” said Dickie. “This is why when we deliver the news we use the same motion tracking software that is based on the Unreal Engine that is used to make the games. We have to use the gamer technology to get that same look to keep it consistent.”

At least in the short term however the experience will differ based on the platform being used to watch it.

“We are for now, a prisoner of the technology,” added Dickie. “You are going to have a different experience on mobile vs. a high-end TV. There is no way around it right now.”

The type of game can also determine how it is presented.

“During a match of any first-person shooter — “Counterstrike: GO,” “Overwatch,” “Call of Duty” — often the presentation will offer a ‘mini-map,’ a simplistic top-down view detailing the layout of the current map and the position of all the players, in a small section of the screen while the majority of screen is either the first-person view of a particular individual or a third-person perspective camera,” explained McKim. “Additional information such as match time, point count, and life totals often frame the screen as well.”

Many eSports are also team-based, so not all of that above information needs to be provided for each player. With up to six players per team, directing the action can be complicated.

“These individuals must be very talented and knowledgeable of the game they are working with,” added McKim. “This entails having to learn the metagame and strategies of professional players or teams and putting themselves in the shoes of a viewer with no experience with the game. Nothing is more off-putting to a viewer than missing a big play because of the camerawork.”

eSports may not need more specialized tools than other sports, but the challenge is one of scale.

“With the popularity of Battle Royale genre games at an all-time high, the ‘optimum’ way to capture this gameplay would be to pull and direct 100-plus competitors’ audio, video, and personal cams,” said Dellario. “This leads to 300+ input needs in this optimal circumstance, which is why it isn’t very common to see broadcasts utilize this depth of content capture.

However with all of the action is occurring within a game there is no worry of a miscall by a referee or illegal actions by the players, as the games won’t allow it. In addition information — notably stats — can be provided in real time in a way not possible in other sports.

“Back only a few decades ago announcers for pro sports didn’t always know the score as it was an individual’s job to keep track,” said Vorhaus. “Now this information on statistics can be pulled up in real time and provided to the audience. There is so much more data that you can push to the screen. eSports is able to provide this information faster than any other sport and that can be very compelling to the viewer who knows — and often plays these games.”

All this could be why eSports promises to be a game changer in more ways than one.