HD becomes MAINSTREAM

Complex market dynamics have dramatically changed the production landscape in the last few years. Since the late 80s, pundits have repeatedly painted each year as the year of HD's breakthrough. Repeatedly, they have been off the mark. It has taken more than time to get this all sorted out, but this year HD became real. We'll take a look at what has happened, what tools are available to producers and where the near term is likely to lead our industry as HD penetration in the consumer market continues its solid climb.

HD explosion

One might argue that the looming FCC DTV deadline, which at the end of this month is only 577 days away, has pumped up the market for consumers and increased the demand for production and the tools needed to support it. That, however, seems to be an exaggeration — no matter what Wall Street thinks. Consumers still appear to be confused about the transition to DTV and even more confused about how to receive HDTV broadcasts without satellite or cable service.

But clearly the explosion in the number of HD channels available nationally has fed the consumer marketplace. Beginning with Discovery HD, which has been highly rated by HD adopters, and the sports broadcasts on ESPN HD and ESPN2 HD, consumers have been treated to stunning pictures and great sound, better than anything they had before. It is hard not to covet a large set with a great picture, and that is precisely what CE suppliers are counting on as they shift more display space to HD product.

The perception and reality that HD meant higher production cost initially held back HD adoption. In the first years of HD delivery, the hardware cost significantly more than equivalent SD products. A camera cost $250,000 a decade ago, and even in 1998 as stations prepared to go on the air with HD for the first time, cameras were 30 percent to 100 percent higher in cost. Lens, VTR, switcher and terminal equipment prices were high by similar margins.

But as the volume has ramped up, the costs for practical HD gear have plummeted, making the differential in complete systems closer to parity, but still with a premium of perhaps 10 percent to 20 percent. At those prices, however, it is easy to see how one might make a financial case for investment in HD capability so long as SD delivery using the same assets is not precluded. With the useful lifetime of television hardware traditionally being six to 10 years, one can find the arguments less specious, especially when reading the long-term prognosis for SD-delivered hardware and the content it is capable of producing.

Producers are always concerned about shelf life of the content, and that is a major issue in situations where the differential in production cost is demonstrable. That is the case when renting a production truck, or studio, for a complex production that one hopes will have “legs” far into the future. If the production product's useful lifetime is limited by the fact that it is only available in SD, the accountants will recommend an HD shoot, even if the release in the short term is SD. But with the number of release channels almost exploding, it is clear that HD is ascendant and available. For instance, DISH Network now has 33 national feeds. Without taking into account the multiple feeds available in premium sports packages like NFL Sunday Ticket, there is significant upward growth in the number of channels available to consumers.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Recent announcements illuminate market trends. HBO plans to convert all 26 of its distribution feeds to HD by the second quarter of 2008. In September, Turner's TBS HD will join TNT HD, which has been on the air for two years, and in the fall, CNN HD will launch. In January at CES, DIRECTV announced the pending launch of 60 new HD channels, including the Turner properties, the Sci-Fi Channel, FX, USA Network, Speed and Turner's Cartoon Network, among others.

HD newscasts

Broadcast HD content has also continued to expand. The NFL will require all broadcasts to be in HD in the future, which is part of rights-holder contracts now. In addition to CNN HD this fall, broadcast networks are converting to HD. FOX News is in the process of converting its main New York headquarters to HD, and NBC Nightly News has been on the air in HD since March.

In a significant change in industry-wide plans, the addition of local HD newscasts has created quite a stir. WRAL-TV in Raleigh, NC, has been broadcasting news in HD since 2001, and this year many stations in large and small markets have converted studio facilities to HD. Like other competitive forces in news, when one station in a market converts to HD, it is hard for the others to avoid eventual conversion for fear of market share loss.

But the conversion to HD presents special challenges for news operations. News is unique in the amount of file footage used on a regular basis, and the potential to have jarring transitions in an HD news broadcast gives producers heartburn. But with the need to use existing footage, choices are hard. Many HD broadcasts use the “pillar-box” approach, and NBC has done that with both file and field footage (which is not native 16:9), as have many local stations. Converting a large news station to HD requires a significant number of new cameras, which can be extremely costly. Holding back until costs come down has actually worked in this case, as HD news cameras have dropped significantly in price in the last year.

Some stations have chosen to use 16:9 SD cameras for news, with upconversion in the control room for playout. In truth, the quality of upconversion from a clean source has become so good that it is tempting to use SD source cameras. Playing into that decision is the lower bandwidth needed to transmit an HD story from the field. With H.264 (MPEG 4 AVC), compression field footage in HD is much more practical, and some stations have chosen to use the advances in compression to allow “full HD” field acquisition. The introduction of HDV cameras will have the effect of making HD production for news much more affordable. Networks and local stations have almost universally chosen to use HDV for at least some field acquisition assignments.

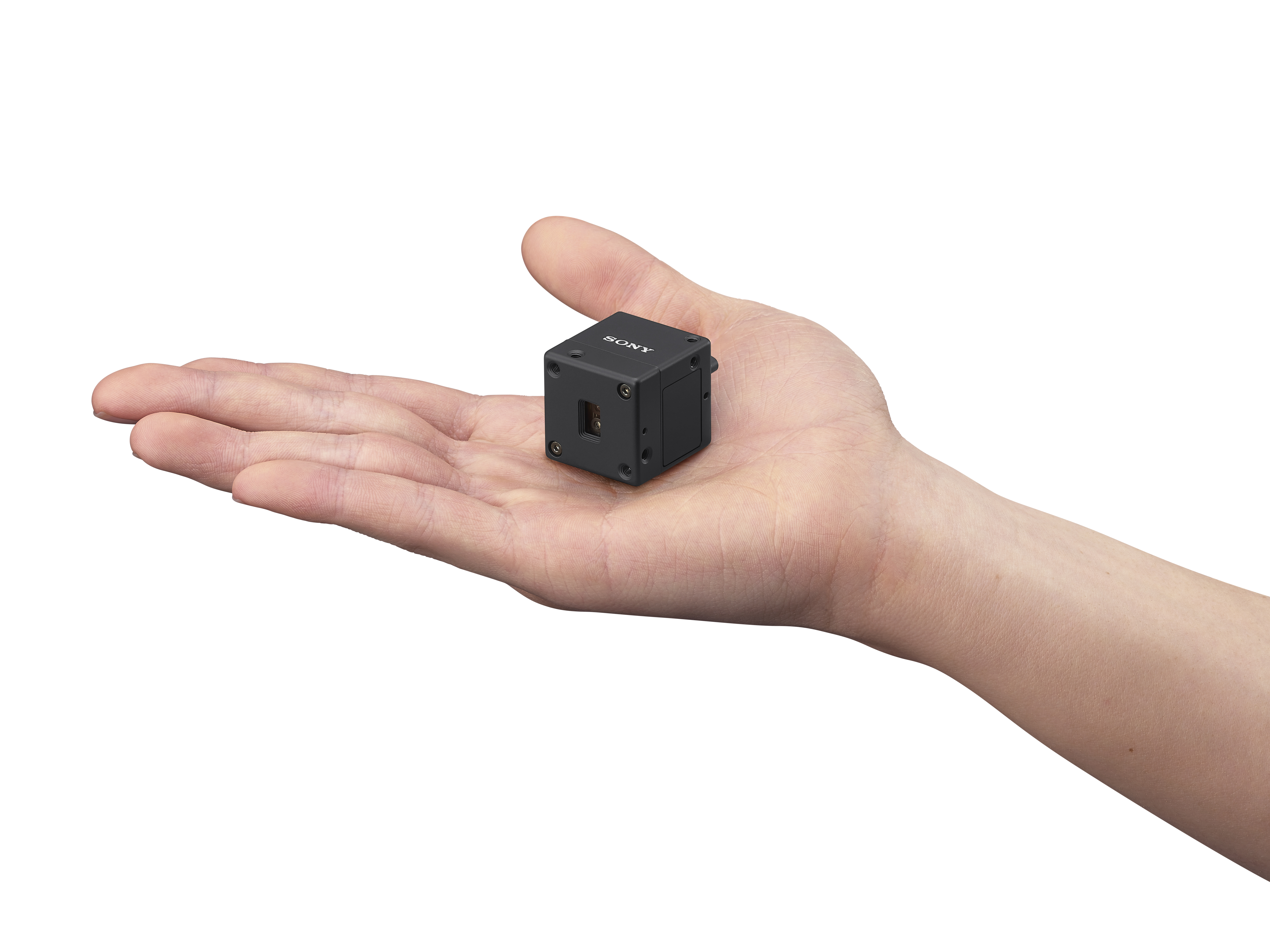

New cameras, including those using memory recording systems, such as the Panasonic AG-HVX200 and Sony XDCAM EX series cameras, have particularly resonated due to the instant access to content that memory recording systems feature. Panasonic's increase in capacity to 16GB per card removes much of the argument about limited recording capacity. With five cards, an HD camera can record 80 minutes, and 32GB cards are expected in the future. Panasonic also has embraced a variant of H.264 that it calls AVC-Intra, which will increase recording time significantly. Sony's recent introduction of XDCAM EX will use a new memory card (SxS) housed in an ExpressCard slot. (ExpressCard will replace Cardbus in the future for portable computing.) At NAB2007, Ikegami and Avid brought back the Editcam line, with both hardened disk packs (FieldPak2) and memory recording module options.

Of course linear editing for HD news would be hard to explain in these days of robust nonlinear editing systems capable of the increased bandwidth of HD production. Again, the advance of technology has tipped the balance in the last year, with lower cost and more complete nonlinear news editing solutions available. Inputs from HDV, XDCAM HD, P2HD, Editcam, Grass Valley's Infinity REV PRO and other sources are compatible with essentially all modern edit systems.

1080p60 production

At the high end, interesting developments have the potential to create a second HD industry just as the first is really catching fire. For years, many have sought the Holy Grail of HDTV — 1080p60 production. But both technology and economics have kept it from the marketplace. In the last year, cameras and other infrastructure elements of a 1080p60 system have become available, and at prices not much above standard HD products. SMPTE has standardized a gigabit interface that supports the higher data rate of 1080p60. (The serial link standard, SMPTE 424, supports the 2.97Gb data rate, and SMPTE 425 defines the source image format mapping.) Routing switchers supporting the new interface standard are on the market, and it seems logical that production switchers will follow as the cost of silicon drops. Though much of what makes up a complete system is not yet available, it seems likely that the future will allow producers to deliver stunning pictures.

But how could that be delivered to the consumer? As it turns out, the progressive scan nature of the image compresses about 30 percent more efficiently than interlaced pictures. Because there are twice the number of frames, that still leaves an increase of about 40 percent more data delivered to the consumer, assuming MPEG-2 coding. But if a service like IPTV, DBS or cable could use H.264, it might be able to deliver a “premium HD” channel without expending any more bits than HD requires today. It is useful to note that all three of those businesses are using advanced coding today, which might make a premium channel consisting of film content simply a matter of time. In addition, live 1080p60 channels could be on the air by the end of the decade.

John Luff is a broadcast technology consultant.