How Will Spectrum Auctions Impact BAS?

WASHINGTON— Broadcasters have enjoyed free and unfettered use of several microwave transmission bands for decades. These Broadcast Auxiliary Service bands at 2, 7 and 13 GHz are used by TV stations for electronic newsgathering, station to transmitter links and inter-city relays. Since they came into use in the 1960s, these channels were pretty much the exclusive domain of broadcast television. Not anymore.

With increasing demand for wireless devices by consumers, the telco industry has been lobbying for more spectrum for wireless services. In the United States, the FCC has been working to accommodate the needs of the wireless industry, and with rulings from Docket 10-153, they have started what many call the “BAS flexibility rule.” Dane Ericksen, senior engineer at Hammett & Edison, a San Francisco-based company that specializes in helping stations with RF and FCC compliance issues, says broadcasters should be cautious.

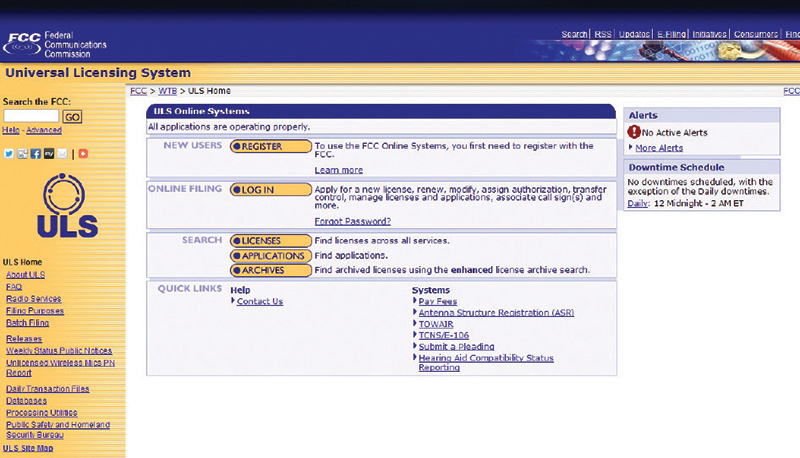

Broadcasters are urged to review their BAS records at the FCC ULS site, http://wireless.fcc.gov/uls “Whenever the commission comes out with the term ‘flexibility’ in their rulemaking, stations better hold onto their spectrum wallets, as it is rarely good news for the incumbent licensees,” Ericksen said. The new ruling specifically opens up the 7 and 13 GHz BAS spectrum to fixed service providers who want to use the spectrum for point-to-point business microwave backhauls to cell sites.

The commission states that they can let the telco operators into BAS bands if they are careful about it. Many in the broadcast RF field agree that it can be done with proper coordination, but they all warn of major issues arising if stations don’t have all their links properly registered with current information in the FCC’s Universal Licensing System.

WHERE ARE THE RECORDS?

The greatest issue for broadcasters is that a large percentage of the records for their fixed link BAS channels may have missing receive end data. Ericksen estimates that 20 percent of 7 GHz links and nearly 30 percent of 13 GHz have improper documentation, or no documentation at all. How did this happen and why does it matter? Broadcasters should listen closely to the answers to these questions.

The problem arose due to a legacy issue with the forms that the FCC originally used to register fixed microwave links. “Prior to 1983, versions of FCC form 313 [application for authorization in the auxiliary radio broadcast services] didn’t have a place to report the receive-end dish’s coordinates, make and model, or even the dish height,” Ericksen said. “This means that decades worth of links were recorded without little to any information about one end of their link! After 1983, form 313 was replaced by common form 601, which became the primary information submittal document for a station’s links for the Universal Licensing System. The ULS is now the master database for all wireless frequency registration. All the original form 313 records with missing receive end data got transferred over to the ULS system.”

Even though public notices were sent out to broadcasters requesting that they update this data, companies like Hammett & Edison discovered that many stations found the new form too hard to navigate and therefore they didn’t spend the time to update all their links.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

In a given market, most stations have a good idea of where the other stations’ dishes and links are located, whether they be STLs, transmitter-studio link or IRCs. There is a professional courtesy among broadcasters in which stations communicate with one another and work out any interference issues among themselves. This is where a new issue arises; fixed service providers now entering a market have no familiarity with the local BAS paths and therefore will only be going by the information listed in the ULS.

An RF test crew from Vislink conduct a survey at a microwave receive site. “Broadcasters should be reviewing all their paperwork,” said Joseph Giardina, chief technology officer and CEO of New York-based microwave systems company, DSI RF Systems. “They should be going to the ULS database and checking their STL, TSL and inter-city relays. It’s the station’s responsibility, no one else’s.”

DSI sells and installs microwave links nationwide and is familiar with making sure new sites are set up properly and registered in the ULS. “You don’t find out until an offending party spends $100K to put in a DS-3 link, and when they fire it up, it causes interference because you didn’t do your paperwork,” Giardina said. Even though the broadcasters may be the primary user in this case, rest assured that the telco will file a lawsuit to recoup their costs.

Christopher Gibbons, vice president of Vislink, a U.K.-based microwave and RF systems company, explains that when a reputable RF systems integrator puts in a new path, many safeguards are put into the process. “We start with a proper overall physical survey that includes site visits, line of- sight verifications and complete RF systems testing,” Gibbons said. There is a good chance a station’s legacy deployments may have been done in-house and not had today’s resources to test and document.

The FCC provides protection for fixed links from interference, but if nobody knows that you are there, the required common carrier notification protection won’t do you any good. Both Ericksen and Giardina point to the changing roles of chief engineers over the years as a reason so many records may be out of date. There was a time when a CE had an assistant CE, a transmitter engineer, office staff and often a legal firm that helped keep the station’s licenses and records up to date. Today, a new CE may find himself in charge of several stations with less staff, fewer resources and without the legacy knowledge of the previously tenured CE.

“How are they going to maintain all the equipment and still find the time to effectively search and update the database without hiring a firm like Comsearch to help out?” Giardina said.

Like Hammett & Edison, Ashburn, Va.-based Comsearch can help a station by providing not only FCC database research, but also evaluation of the station’s link data to make sure that it is current.

Along with missing data about the receive antenna itself, most map coordinates of dishes were originally done with topographical maps rather than modern global positioning systems. There is a chance those previous estimations are not as precise as they need to be in a newer, more crowded microwave user landscape.

POTENTIAL FOR INTERFERENCE

In addition to record-keeping, interference issues are also expected to be a cause for concern in this new spectrum environment.

BAS spectrum is “no longer a broadcaster-only band,” Ericksen said.

Telcos currently use the 6, 11 and 18 GHz bands for their cellular tower backhauls. Where broadcasters once had exclusive use of the 2, 7 and 13 GHz bands, they now will have to coexist with the telcos as they move from their filled bands and into broadcasters.

“As cell companies begin to proliferate the band for more backhaul needs, this could become an issue,” Giardina said. Just as they filled up the bands they previously used, they may overcrowd the BAS bands as well.

“This isn’t like the analog to digital transition,” said Jay Adrick, vice president of Broadcast Technologies at Harris Broadcast. “In this case there is no alternative spectrum.” Adrick has seen the same issues arise overseas where wireless operators are constantly looking for more spectrum to expand their services.

Both the lower frequency 2 GHz band and the higher 7–13 GHz bands face different challenges. “2 GHz is a very important band to broadcasters,” Adrick said. Where higher frequencies like 13 GHz may be good for only 25 miles, the 2 GHz signals can travel hundreds of miles with less susceptibility of rain fade. For this reason the 2 GHz bands are popular for ENG and inter-city relay links. At the request of the SBE, “this part of the 2 GHz band was added to the TV pickup license for ENG use,” Ericksen said, who estimates that half of all TV pickup licenses have added their fixed ENG sites to that license. This means that those sites are protected.

Protection means recourse if a telco fires up their equipment unknowingly in the path of, or adjacent to, existing broadcast equipment and causes interference. They will be required to adjust their signal, provide filters for the broadcaster, or vacate the channel entirely. There are several scenarios where a newcomer can step on another’s channel, if inaccurate receive coordinates were filed for an STL and a new telco transmitter is placed too close and overrides the intended receive signal to a path that wasn’t originally engineered to deal with more crowded spectrum.

“I have not heard from our clients on any interference yet in STL bands,” DSI’s Giardina said. “If the installation was done correctly and engineered with a certain factor of resilience there should be no interference.” Giardina also explained that unless corners are cut on the installation or if there is a ULS issue, STL and relay links should not experience interference. He always recommends going with a larger dish and even a shroud or notch filter in high RF environments to reduce the chance of a compromised signal.

On the higher frequencies, a high-performance shrouded antenna may be a requirement, even though the newer IP-based microwave radios used in broadcast can often avoid interference by just switching channels. The fact that telco backhauls are high bandwidth bidirectional data feeds in a formerly unidirectional band may cause issues as more of these stations appear and possibly create frequency congestion.

“We recommend an 8-foot antenna on both 7 and 13 GHz paths,” said Vislink’s Gibbons, who also recommended that broadcasters pay attention to those Prior Coordination Notification notices they get from frequency coordinators. Comparing the notices against their existing infrastructure and keeping them on file can help prevent issues from arising and troubleshoot them when and if they occur.

PLAYING THE ODDS

Some broadcasters look at telcos as “trespassing” on their band, but as Giardina said, “the reality is most telco links will take up only a small portion of the spectrum in any one area. This same channel can be used elsewhere in a different direction that won’t cause interference with the first one or others. What are the odds of someone being on axis +/–5 degrees to be able to interfere with you?” With the ability to use point radius information from the ULS database to search the radiation patterns, modern tools make it easier than ever to ensure a station’s vital links are protected.

Vislink’s Gibbons agrees. “The carrier typically doesn’t use higher elevation or common locations used by broadcasters,” he said. This tendency to be located at lower elevations does provide significant separation from paths broadcasters typically use for ENG and STLs.

The fact is that the telcos don’t want to waste money on a link that can’t or won’t work, so if the built-in safeguards do work, there should be minimal issues. A station that does not properly maintain their links in the ULS can spend more in legal fees fighting lawsuits than simply correcting database errors. To make sure that the safeguards protect the station’s valuable spectrum assignments, a station either has to put in the effort necessary to confirm all their records are up to date on the ULS, or go with a reputable firm whose tight criteria and modern tools will guarantee the links will be protected.