Keep Your Transmitting Plant at Peak Operation

A clean, well-lighted transmitter plant — does yours look like this? (photo credit, Hitachi Kokusai Electric Comark LLC)

ALEXANDRIA, VA. — As related in the first part of this article, there was a time when radio and TV transmitting facilities were a station’s pride and joy and continuously staffed. Unfortunately, this is no longer the case. Transmitting plants are now for the most part “out of sight, out of mind” until something “bad” happens (translation: going off the air unexpectedly).

However, with a little of that due diligence we’re always hearing about, there’s really no excuse for a facility to suffer downtime. Part one examined transmitting towers and this installment goes inside the buildings located beneath those lofty structures.

MAKE TIME TO SAVE TIME

Just as with periodic tower inspections, regular preventative maintenance can keep you on the air without interruptions. With fewer and fewer resources available and always more and more to do, it’s tempting to place transmitter PM on the bottom of the list and address the “fun stuff” first, but don’t. Create an inspection schedule/checklist and stay with it. If the facility is remotely located, that’s all the more reason for regular visits to see if something may be going out of kilter from normal wear and tear, or perhaps has had a little help from outside forces.

Building security should be foremost on the list. Hopefully, you’ve got some sort of remote surveillance system or service in place to notify you of an opened door or HVAC failure. However, remote telemetry doesn’t always catch less obvious items, such as locks or outside electrical gear and grounding systems that have been tampered with. It’s a good idea to do a complete walkabout to check for signs that someone has tampered with gear so as to make it unreliable or unusable when it’s really needed.

‘CRITTERS’ NOT WELCOME

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Humans aren’t the only intruders you need to worry about. Transmitters and equipment racks work best in comfortable temperatures and humidity levels. Small animals enjoy these conditions too and will go out of their way to seek them, especially when someone else is paying the bills.

Flying and crawling insects somehow have a sixth sense when it comes to accessing protected enclosures. While they mean no harm, wasps, bees and ants can cause damage when they set up shop in power panels, generator control boxes, ductwork, or other out-of-the-way places. It’s a good idea to pull panel covers and access plates on a regular basis to check for squatters. Caution is advised, though, as some of these species don’t like to be disturbed. If colonies are discovered, do your best to identify how access was gained and seal off these “ports-of-entry.”

Critters a bit higher on the evolutionary scale—birds, reptiles, and mice (especially the latter) can be. If “Mickey and Minnie” do take up abode you’ll soon find out how destructive they can be. In addition to unauthorized document shredding, they’re not too meticulous when it comes to bathroom habits, instantly ruining items or setting the stage for eventual ruination by corrosion. They love warmth for themselves and their offspring, and tend to seek out heat-producing gear, sometimes building secret and elaborate nests under a chassis or deck. OSHA safety regs don’t apply to mice and in many cases they manage to connect with a voltage source and zap themselves. This can either cause an immediate equipment failure or create a more subtle and difficult to diagnose condition involving decomposition.

If you notice evidence of a rodent invasion, it’s probably best to bring in professional help. In addition to extermination they also know where to look for ingress ports and know how to make a facility mouse/rat-unfriendly.

Reptiles—snakes in particular—also seem drawn to transmitter buildings, and can enter through very small openings. They can either scare the dickens out of you when you unsuspectingly discover and disturb them, or cause equipment failure.

James Gott, senior maintenance engineer at Paducah, Kentucky’s WPSD-TV, related a transmitter issue triggered by a curious reptile.

After remotely observing that one of the station’s dual Harris TV-30L transmitters had dropped off line, he made the 30 minute drive to the transmitter site and tried resetting the failed transmitter’s high voltage supply several times without success.

It just kept tripping off,” said Gott. “I removed the back panel to get to the high voltage parts…and noticed that a big greenish-brown snake had crawled into the cabinet and had gotten across one of the caps.”

Gott reported that he removed the snake and then cleaned up the capacitor with denatured alcohol. The rig came back up, but the snake turned out to be a total loss.

“I was not gonna try ‘mouth-to-mouth’ with a snake,” quipped Gott.

IF IT CAN HAPPEN, IT WILL!

Transmitter meters are isolated from human contact by a protective glass or plastic cover for good reason. Never remove such covers.

Another area that needs scrutiny—especially if you’re new to a legacy transmitting facility—are undocumented changes made by former employees. Never assume anything!

Fred Krampits, a customer service engineer at Hitachi Kokusai Electric Comark LLC, relates an incident in which a newly hired engineer received a very severe electric shock while checking out a transmitter problem. The cause was a high voltage interlock that had been bypassed by someone in the past and never documented. Fortunately, the victim had followed the rule of never doing transmitter maintenance alone and his co-worker was able to administer CPR and call in emergency medical personnel.

In addition to checking for compromised interlocks, Krampits also strongly suggests investigating the condition of other interlocks and safeguards which might have failed of their own accord, and which in addition to posing safety issues could lead to expensive repairs.

“It’s very easy to quickly destroy a $40,000 IOT if a loss-of-coolant interlock isn’t working properly,” said Krampits.

MAKE TIME TO CHECK THAT DOCUMENTATION

If you’re new to a facility, it also might make good sense to dust off the manufacturer’s installation manuals to see if everything was done properly when the transmitter was first installed. There’s the case of an installation in the good ole NTSC days where the manufacturer’s equipment floor plan was ignored, as the licensee wanted to save some money and had the building contractor shave a few feet off the structure’s suggested dimensions. This necessitated rearranging some of the larger gear once it was delivered. Despite a somewhat cramped layout, everything did go together and all was well until about a year when the visual transmitter’s heat exchanger suffered a massive core leak. Unfortunately, what could have been perhaps a single day’s outage turned into a real nightmare. To gain access to the visual heat exchanger’s core, both the aural transmitter and its heat exchanger had to be disconnected and moved out of the way, killing any notion of staying on the air by multiplexing signals through the aural amplifier. Three days of operations were lost and a very large overtime bill racked up. Need I mention that this outage occurred during a rating sweeps period!

The same sort of “gotcha” can happen when older facilities are modified or original equipment is replaced with newer gear. It’s time well spent to study the relationship of transmitter power supplies, amplifier cubicles, HVAC equipment and other items within your transmitter building to see if easy access to repair/remove/replace an item has been made difficult by placement of other gear. This includes access to outside doorways, which may once have in the clear but is now impeded by added equipment or interior construction. Even if access doesn’t appear to be a problem, try and imagine worse case scenarios regarding large item failures and develop a plan if the unthinkable does happen. Such homework may prove to be very valuable.

Speaking of documentation, do you have a complete set of manuals covering everything at the transmitter facility? Krampits noted that it’s not uncommon for customers to call his company’s help desk for assistance in getting a transmitter back on the air; however, when the troubleshooting steps are suggested it’s learned that the equipment manuals and diagrams are back at the studio, or have just plain “gone missing.”

“It’s awfully hard to try and take someone through transmitter wiring when there’s no schematic available,” Krampits said.

Is your transmitter plant ready for “the big one?” This AM facility was constructed with flooding from a nearby river in mind. Everything is located above a worse-case waterline.

Joe Turbolski, director of sales at Hitachi Kokusai Comark, observed that in today’s world, there’s really no excuse for not having service information available where it’s needed, as his company and others have been issuing such information on CD ROM and memory sticks. Also, in many cases, manuals are available for downloading from the manufacturer’s website. It’s fine if you want to keep transmitter equipment documentation in your office at the studio, but be sure you’ve printed out duplicate information for use at the transmitter site, and do this way ahead of the game. Don’t count on a rarely-used compute or printer at the transmitter to be working when it’s crunch time.

WHEN IN DOUBT, CALL IN AN EXPERT

In today’s environment, on-site transmitter engineers and station employees who did nothing but RF work really don’t exist anymore, so perhaps when some really serious transmitter maintenance is needed it may be better to bring in someone with a thorough background in this area than trying to do it yourself. The potential for personal harm and very expensive consequences can be very high if your skill set isn’t what it should be.

One such specialist is Mark Hills, principal engineer at s2one Inc. He’s been involved in RF work for more than three decades, and a few years ago decided to launch a business to assist those in need of RF expertise.

“A lack of qualified RF people was the reason I started my company,” said Hills. “With the transition to ATSC, I saw a huge volume of transmitters and a shortage of station employees with RF experience. People with transmitter experience have mostly retired.”

Hills visits some 75-80 television transmitter installations in the course of a year, with customers including everyone from mom-and-pop operations to major groups.

When asked about some of the problems he’s seen associated with lack of RF training, he was quick to recall a visit to a major market facility with an IOT transmitter.

“The meters were supposed to be behind a Plexiglas screen, but it had been removed by the operator,” said Hills. “He said that he was fed up with having to remove it to change lamps. He wasn’t aware that there was 36 kilovolts there.”

In another case, Hills related performing an inspection on a station recently purchased by a group owner. He observed that the transmission line flanges were assembled with only about half of the bolts required and that the line was held in place with ordinary rope.

At another site, Hills found the ATSC transmitter grossly mistuned.

“It made a picture, but things were very far out,” he said. “Nobody checked to see if the ‘shoulders’ were in spec. You can do nothing for a while, but it’s going to catch up with you sooner or later.

“Fortunately, there are still some broadcasters who want to do things right. That’s where I can be of assistance. Chief engineers send studio people up to the transmitter to work with me and try and learn something. I always make a point of going through safety issues.”

Hills remarks were echoed by Roz Clark who is director of technical operations with Cox Media Group’s Tampa and Orlando, Fla. radio properties and oversees management of 13 radio stations in those markets.

“There is no such thing as a transmitter ‘guy’ who’s at the transmitter every day,” said Clark. “Those days are long over. Some station operators have gone to a mode of ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t worry about it—just take care of things when they break.’ That’s a risk that some companies take.”

Clark advocates a strict schedule of routine maintenance, with a visit to transmitter sites on a weekly basis.

MAKE SURE IT’S GOING TO WORK BEFORE THE EMERGENCY OCCURS

“The operating condition of everything on line should be noted,” said Clark. “And also the things that are not on-line at that time at the time of inspection such as backup power systems, generator power, alternate transmitters and other systems.”

He stressed that too much emphasis can’t be placed on keeping backup power sources ready to operate.

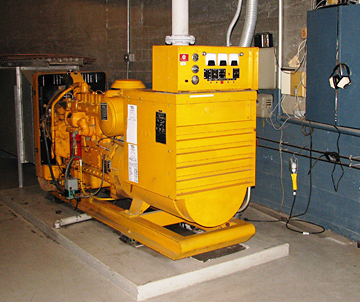

While locating a backup generator in a transmitter building’s basement may seem like a good idea, there can be some downsides.

“Generators need to be started at least once a month and a check made to be sure everything is operating normally,” said Clark. “And don’t neglect fuel supplies; diesel fuel isn’t what it used to be—shelf life is much shorter due to biofuel and a lack of sulfur. It can break down and grow bacteria and all kinds of things. At least yearly, you should bring in someone who specializes in fuel treatment to filter and purify your fuel. They pump from the bottom of the tank and filter until the fuel is at a specified clarity. They also take samples and send these to a lab for further analysis to determine the fuel’s combustibility and other qualities, and will recommend if any additives are needed to extend the fuel’s life.”

He also pointed out that reliance on in-line diesel fuel filters is not enough.

“Your filter will capture these contaminates, but they will eventually clog it and your generator will not run.”

The physical location of a backup generator and its associated fuel tank is sometimes taken for granted, but this can spell success or failure in times of an emergency. At transmitter buildings with basements, it’s tempting to install the generator down there. However, there are downsides. A big takeaway from the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor disaster is that backup generators don’t work very well when they’re under water. It’s best to place them on high ground—a pad or other support well above a worse-case flooding scenario.

Inside placement of fuel tanks is also problematic. There’s always the possibility of a leak that could go unnoticed long enough for the tank to completely empty its contents in the enclosed space. In addition to the safety hazard, cleanup is going to be involved and costly. An outside location with a basin large enough to contain a leak is the only way to go.

Electrical power panels at transmitter sites need periodic attention too.

“Best practice is to get a thermal imaging report on all electrical systems,” said Clark. “This is where someone comes in with an infrared camera and can spot areas that are heating. This will help you cure problems before they become a crisis.”

DON’T PUT IT OFF ANY LONGER

We’re all busy in this world of multitasking, however, a little time spent in periodically checking things at your transmitter site and planning for contingencies can pay big rewards. Perhaps pioneer superpower radio broadcaster and quack physician Dr. John R. Brinkley said it best in his appeal to his radio audience to seek his services:

“Don’t wait until it’s everlastingly too late!”

James O’Neal is a retired broadcast engineer with more than 35 years of experience in the field. For the past 10 years he has served as technology editor at TV Technology magazine.