Making Sense of UHDTV

SEATTLE—Ultra high definition is becoming ever more dominant as the sets become the de facto standard in consumer electronics and more UHD programming becomes available on cable, satellite and streaming sources. What’s this all about, and how does it relate to HDTV?

UHDTV is based on the specifications contained in ITU-R BT.2020, which specifies two resolutions: 8K, which is 7,680 horizontal pixels per line by 4,320 lines vertically; and 4K, which is 3,840 horizontal pixels per line by 2,160 lines vertically. Both resolutions have an aspect ratio of 16:9, the same aspect ratio as HDTV, and square pixels, which simply means that the pixels themselves are square, with an aspect ratio of 1:1, as are HDTV pixels.

While common practice in Europe, in the U.S.—before high definition came onto the scene two decades ago—networks and broadcasters refused to “letterbox” wide aspect ratio films onto 4:3 NTSC TV screens, which would leave black bands above and below the frame.

This was done because when letterboxing was experimented with, it resulted in many calls from viewers. Thus, when theatrical films were transferred to video, they were “panned and scanned,” so that the most important parts of the film image filled the TV screen and the excess was discarded. With the advent of HDTV, letterboxing of wide-screen film features became the standard practice.

A WIDE SWATH

Rec. 2020 specifies only progressive scan frame rates, which makes great sense in light of the fact that all advanced displays are progressively scanned by their nature, and interlaced images must be deinterlaced before they’re displayed. The frame rates specified include 24p, 25p, 30p, 50p, 60p, 100p and 120p, plus the fractional frame rates 23.976p, 29.97p, 59.94p and 119.88p.

The inclusion of fractional frame rates recognizes the installed base of television distribution facilities and the vast quantity of U.S. legacy programming available at fractional frame rates, including analog NTSC, digital NTSC and ITU-R BT.601 component digital video. The use of the 59.94 Hz rate facilitated the Rec. 601 digital video sample rate of 13.5 MHz for both 59.94 and 50 Hz systems, as 13.5 MHz is exactly 6x2.5 MHz, the NTSC horizontal line rate is exactly 2.25/143 MHz and the PAL horizontal line rate is exactly 2.25/144 MHz.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Thus there is an identical number of samples per line in the two systems, and it would not work if NTSC had 60 Hz parameters. So, as I wrote a decade ago in these pages, the fractional frame rates are still not going away in the foreseeable future.

PULLDOWN STILL NEEDED

Before we leave frame rate, we note that one of the frame rates of UHDTV, as well as HDTV, is 24p, (actually 23.976p). ATSC includes the ability to transmit 1920x1080 at 23.976p video, while the HD receiver has the ability to add 2/3 pulldown and display the images at 29.97 interlaced or 59.94 progressive frames per second.

While there is no mention of pulldown in Rec. 2020 or the Ultra HD Forum guidelines, it is essential to add pulldown; otherwise, viewing 24p images would result in highly objectionable flicker. Film sourcing has been used on television for many decades, and 2/3 pulldown has always been used to reduce flicker. In this way, the TV viewer is exposed to 59.94 large-area light flashes per second, which is sufficient to eliminate flicker even when watching a TV screen in a brightly-lit room.

When film is projected in a dark theater, each frame is double-shuttered, resulting in 48 large-area light flashes per second, which is sufficient to eliminate perceptible flicker under those conditions. Motion artifacts of 2/3 pulldown are, incidentally, essential to the “suspension of disbelief” when watching a film source on TV.

59.94 Hz video, as seen in pure video recordings, produces what is popularly referred to as the “the soap-opera effect,” while 2/3 pulldown is achieved by displaying alternate 24 Hz film frames in a 2/3/2/3/2/3… sequence. That is to say, the first film frame is displayed twice, the second frame three times, the third frame twice, etc. The resultant judder artifacts cause problems with some camera pans, etc., but it is essential to the display of 24 Hz film on television, and every filmmaker is very much aware of it.

‘FILMMAKER MODE’

We will concentrate on 4K resolution, as this is the current state of the art available to the consumer. As is apparent, 4K resolution is about twice the 1920x1080p HD resolution. In addition to resolution, the other enhancements brought about by UHDTV include frame rates, as discussed above, and colorimetry.

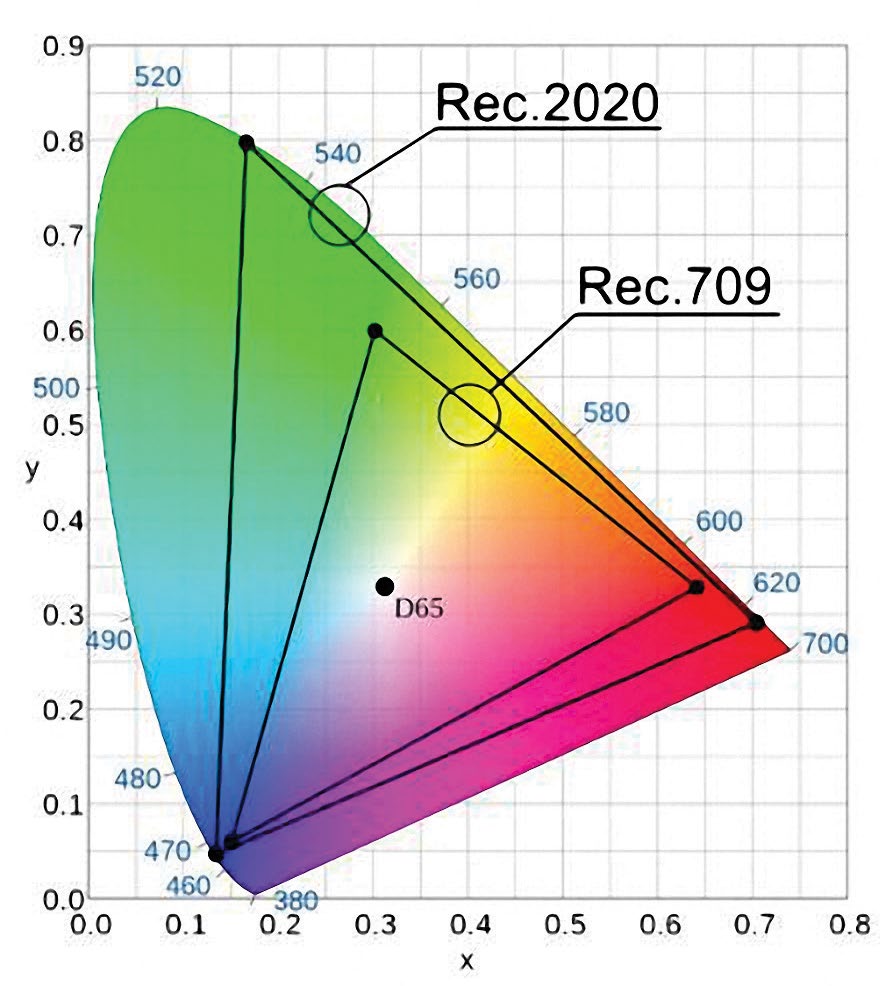

The UHD Alliance, a consortium of broadcasters, vendors and Hollywood studios, in their most recent guidelines, specify that UHDTV content masters and distribution channels shall use Rec. 2020 color space, which incorporates a much wider color gamut than the ITU-R BT.709 color space, which is used in HD. The reader may find diagrams showing the gamuts of both color spaces online.

Here is how various color spaces compare with CIE 1931 color space, which includes all colors the human visual system can perceive:

• ITU Rec. 709 covers 35.9% of CIE 1931

• Adobe RGB covers 52.1% of CIE 1931

• DCI-P3, the digital cinema color space, covers 45.5% of CIE 1931

• Rec. 2020 covers 75.8% of CIE 1931

Additionally, Rec. 2020 specifies color bit depths of 10 and 12 bits, although the UHD Alliance currently specifies only 10 bits, plus High Dynamic Range per SMPTE ST 2084.1

This brings us to the concerns expressed by a consortium of film producers, who are calling for an easy way to set a UHDTV set to “Filmmaker Mode” as laid out in techcrunch.com:

• Turn off all motion-smoothing effects

• Turn off noise reduction, sharpening and other after-the-fact processing effects

• Automatically display the media in its intended aspect ratio/frame rate.

• Turn off overscan, unless required by the video

• Set the white point color to the widely used D65 standard

Addressing these points—the first two, related to motion smoothing, noise reduction, sharpening, etc.—are not part of Rec. 2020 or the UHD Alliance, and probably should be shut off as a matter of course, unless the content cries out for them. The set should also display the content in its intended aspect ratio, as is the current practice in HDTV distribution.

Suggesting “turn off overscan, unless required by the video,” would seem to be covered by the suggestion about aspect ratio, but it is unclear what “unless required by the video” means. The D65 white point is a part of both the Rec. 709 and the Rec. 2020 color spaces. Finally, as explained elsewhere in this article, it is a bad idea to display anything at 24fps, as this generates way too much large-area flicker under any viewing conditions.

One last point. There have been at least a few people who have inquired as to whether it is time to eliminate fractional frame rates in the U.S. I refer you to my article “Will the End of NTSC be the end of 59.94?” in the Jan. 9, 2008, issue of TV Technology. That article still stands, as evidenced by the inclusion of fractional frame rates in the Rec. 2020 standard. As has been true since NTSC was specified in the 1940’s, today’s television technology developments are informed by and based on what came before.

Randy Hoffner is a retired broadcast network executive and long-time contributor to TV Technology.