NTSC Color Celebrates 60th Anniversary

WASHINGTON — Ever hear of the “color wars?” If not, read on. Though not covered in mainstream history books, these wars cost millions of dollars and untold thousands of man hours to prosecute before ending 60 years ago.

The formal close came on Dec. 17, 1953, a date little remembered, but one that is important as it marked the official end of a television industry conflict that simmered and boiled for half a decade. The skirmish involved two communications giants—the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS)—and had roots extending back to March 1940 and a “chance” viewing of a motion picture by CBS’s television engineering director, Peter Goldmark.

Goldmark and his new bride were honeymooning in Canada and had a substantial layover at the Montreal train station. While waiting, they decided to take in a new Hollywood release, “Gone With the Wind.” Goldmark had never seen a Technicolor film and was totally smitten by what he saw—to the extent that he decided to immediately move from black and white TV research into color once he returned from his trip. In a few months Goldmark was demonstrating color video to the FCC. Its chairman, James Fly, was impressed— so much so that the network gave Goldmark the green light to continue color R&D. However, America’s entry into World War II eventually put the project on hold.

After global hostilities ceased, Goldmark returned to color work, and in doing so unintentionally ignited a skirmish that was to last almost as long as the war which halted his research.

THE BATTLE BEGINS

Goldmark was soon transmitting color signals throughout the New York City via the world’s first UHF television transmitter and CBS made sure that the FCC and its new chair, Charles Denny, were aware of these over-the-air demos. (The CBS system provided high-quality color images.) According to Goldmark, the lobbying efforts seemed to be paying off, with Denny possibly even more impressed than his precursor. Goldmark and his bosses felt that the commission would soon allow the network to move from experimental to commercial colorcasting.

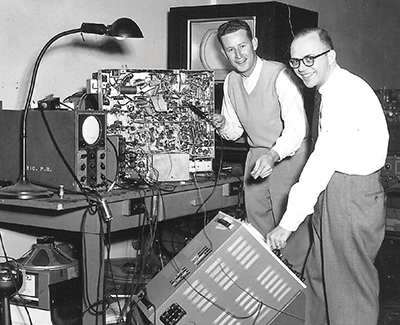

Ray Bintliff (R) worked as an RCA field engineer at the company’s color testing lab in Astoria, Queens, N.Y. He and other RCA personnel got their first exposure to color via RCA’s Model 5 developmental set (the massive chassis and color CRT Jig are seen on the workbench). RCA’s chieftain, David Sarnoff, who had spent a lot of shareholder money in perfecting monochrome television was incensed that upstart CBS seemed to have beaten his company to the punch on color, and he was not about to let CBS just walk away with the prize.

Sarnoff accelerated RCA’s own efforts to develop a color system—one without the major, but underplayed, flaw in Goldmark’s system—it was not backwardly compatible with the very large number of black and white receivers already in consumers’ homes; the CBS color line and field frequencies varied so greatly from the U.S 525/60 television standard that existing sets could not produce a picture when with fed CBS color video.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The war began to heat up.

Surprisingly, or maybe not, it wasn’t too long after Goldmark charmed Denny with his color demos that the FCC chair relinquished his position to accept a high-level job at NBC.

Goldmark kept tweaking his system, finally locking into a 405-line/144-field version that fit into existing six MHz channels. All the while RCA struggled to perfect “backwardly compatible” color, with their own approach for fitting three color images into a standard broadcast channel. However, RCA’s early color demos didn’t come off nearly as well as CBS’s, and after some heated hearings the FCC decreed CBS the winner in the fall of 1950.

Sarnoff was now doubly incensed and took the matter to the courts, effectively freezing CBS’s victory. This delaying tactic also helped to make an even greater case against non-compatible CBS color video, as the meantime, the growing interest in television resulted in the manufacture and sale of even larger numbers of 525/60 black and white TV that wouldn’t work with the CBS system. The case eventually worked its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in May 1951 upheld the FCC’s authority to set a color standard. CBS formally launched color broadcasts the next month, but soon realized that even though they’d won the battle, there were no spoils for the victor. Whenever CBS turned on the color, viewership plummeted to the vanishing point. This could have been predicted, as no established TV set builder could be persuaded to build sets for the CBS standard, requiring the network to go into the manufacturing business itself. Only about 200 CBS color sets were ever produced. After four months of sinking ratings, CBS tucked its multicolored tail and quietly slinked away from colorcasting.

PEACE AT LAST— THE BIRTH OF NTSC COLOR

Soon after CBS tossed in the towel, a second National Television System Committee was convened (the first had been formed in 1941 to hammer out monochrome standards) to develop a color system that wouldn’t blindside black and white sets and one that all parties could agree upon. RCA was a major player, but a number of other television interests also formed the committee. Even Goldmark joined.

NBC initially used this colorized version of the network’s “chimes” to announce color broadcasts; they were later replaced by the NBC peacock. By mid-1953, the second NTSC’s work was essentially complete; only a bit of fine tuning and FCC approval remained. Finally, late in the afternoon of Dec.17, the long-awaited word came from Washington making it legal to transmit the NTSC color.

RCA/NBC immediately hoisted the victory flag by issuing a special “NBC Color Television News” press release, advising that the network had “raced off to a lightning start in color television by putting a color signal on the network at 5:32 p.m., EST, within minutes after announcement of approval of compatible color signal specifications for television by the Federal Communications Commission.”

The release somehow managed to blindside all of the contributions made to the compatible color system by other players—notably Hazeltine Labs and Philco, bluntly declaring that “RCA developed the compatible color system.”

CBS wasn’t quite ready to completely throw in the towel, though. Across town from 30 Rock, Richard O’Brien, then a CBS Television project engineer and later the network’s director of engineering, had also been waiting for the FCC announcement. He had at his disposal a small studio created for color program testing and decided to produce the world’s first NTSC color television program. NBC signaled the era of NTSC color with only the airing of a color slide.

The Tale of ‘Model 5’

Does a falling tree make a sound if there’s no one in the forest to hear? Surely these words must have been in the minds of RCA engineers when the color program got into high gear.

RCA’s Model 5 color television receiver Even though standards had not been locked into place, color television receivers would be needed for testing and to be ready for demos when the FCC eventually signed off on NTSC. According to information provided by Ray Bintliff who worked as a field engineer for RCA in 1953, RCA’s Bloomington, Ind. plant began turning out limited quantities of a pre-production set, the “Model 5” that was designed for the color specs submitted to the FCC by the NTSC. These were sent to locations around New York City, including NBC executives’ homes and the RCA color laboratory facility in Astoria, Queens where Bintliff worked. (The Queens lab was on the receiving end of the legendary “blue banana” joke perpetrated by RCA’s Dr. George Brown.)

Bintliff estimated that a few hundred Model 5s were produced. In anticipation of what was likely to be a favorable FCC NTSC decision, early in December 1953 Model 5s began to be deployed in fair numbers to locations in cities with stations that could transmit the new color signal. The plan was to give the public its first real peak at compatible color with the eye candy being the Tournament of Roses parade. Bintliff, now 91, recalls spending New Year’s Eve at the New Haven, Conn. armory building adjusting the five model 5s sent there in order to be ready for the Jan. 1, 1954 event.

The model 5 evolved into RCA’s first commercially marketed color set, the Merrill or “CT- 100,” which began to appear at RCA dealers in late spring 1954. It carried a price tag of some $1,000 (about $8,600 in today’s money). Needless to say, few were sold.

—James O’Neal

“I was in our special color control room at Studio 71 in the CBS building when the FCC announcement was made and thought it would be a good idea to put together a color show,” said O’Brien. “I called a producer who had been working with us and he agreed. He got Dr. [Frank] Stanton, [prize fighter] Rocky Marciano who was there for a rehearsal, and Mike Wallace and we did a show. It lasted about half an hour.” CBS at the time had been using the studio for rehearsing a pilot or developmental color program called the “New Review.”

Speaking of the angst between CBS and RCA over developing color, O’Brien, now 97, stated “This formally ended it.”

FIRST TRANSCONTINENTAL BROADCAST

RCA/NBC was not to be outdone, pulling its own color coup slightly more than two weeks later with the origination of the first coast-to-coast NTSC color broadcast— coverage of the Tournament of Roses Parade on Jan. 1, 1954.

By then at least 23 NBC affiliates were equipped to handle the new NTSC video and transmitted the parade in color.

Although NTSC broadcasts formally ended in June 2009 with the mandatory conversion to DTV by U.S. full-power stations, that color standard remains in use at some low-power stations, cable systems, and in several nations that have not switched off analog. Set-top boxes continue to produce NTSC signals for viewers who have yet to purchase digital sets. There are also the millions (perhaps billions) of NTSC-encoded recordings. It will be a long, long, time before NTSC color disappears completely. Happy 60th birthday!

The author wishes to thank Richard O’Brien, Ray Bintliff, Steve Dichter, Don Kent, and especially, Ed Reitan, for their assistance in putting together this article. Those interested in further pursuing the history of color television are invited to visit Mr. Reitan’s website, http://www. edreitan.com which provides additional information on the CBS and RCA color television systems.

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as editor-in-chief of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a Life Member of the IEEE and the SBE.