Recreating the Sports Fan Experience Virtually

Television attempts to replicate the excitement of major league sports amid a pandemic

BALTIMORE—The abbreviated regular season for Major League Baseball (MLB) is already more than half over, but the big story in this COVID-19 scarred season doesn’t seem to concern what’s happening on the field.

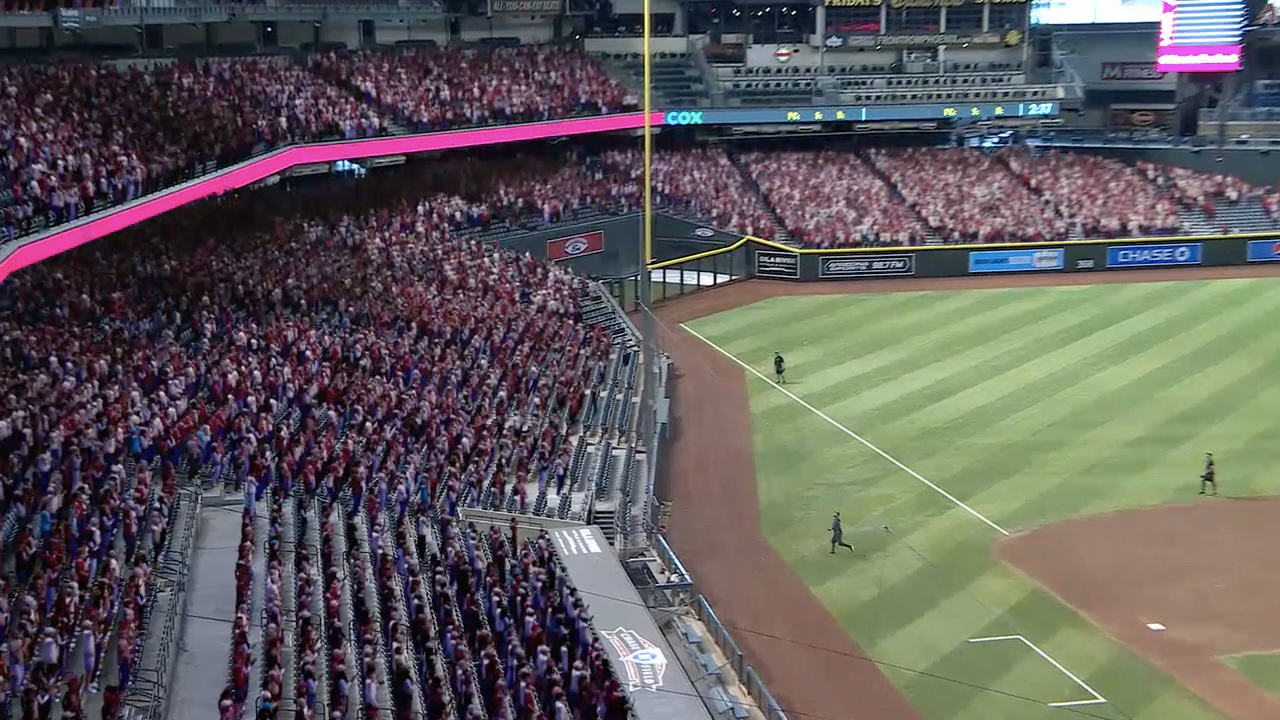

Some viewers might say it’s about heightening the fan experience. The season has featured, at various points, cardboard cutouts of fans in the pretty people seats, groups of virtual fans that fill a 40,000-seat ballpark and sounds of the game that are piped in and accentuated during tape-measure homers or a game-ending strikeouts—often against a background of virtual ads that are appearing in areas of the venue where they are not normally seen.

That’s about making today’s game more appealing to players who aren’t used to playing in empty steel and concrete caverns and fans who are used to heightened broadcast production.

For MLB, Fox Sports is using augmented reality, “with graphic recreations of fans from video game engines and tracking them with four cameras to make the event look real,” said Michael Davies, senior vice president, field and tech operations for the sports net. “At the moment, it has its limitations. For instance, when a player appears between the camera and the fans, it breaks the illusion.”

Still, the Fox Sports approach is a far cry from the first sporting events that aired post-COVID-19 this spring, such as ESPN’s Korean Baseball Organization [KBO] broadcasts that featured not only the cutouts, but stuffed animals.

THE COMEBACK

Davies said Fox Sports has been using “balanced crowd sounds, which don’t react too much to the action. We’re doing a separate crowd mix for TV, which is a bit more reactionary and dynamic. Overall, we have found that viewers notice when crowd noise isn’t there, but you don’t notice when it is; so we’re looking to make the viewing experience seem somewhat normal.”

Fox Sports got in the game, so to speak, with auto racing, with real drivers in virtual cars, then real NASCAR races in May. “We didn’t need crowd audio for NASCAR because it’s normally not a big factor in the mix,” he said. “Then NASCAR gradually began adding fans, which got us back to work during the COVID-19 era—and we got through the broadcasts with no infections.”

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

That’s due, in part, to fewer people on site working on the productions. “We moved some of our replay and graphics people to our base in Los Angeles, and the announcers and producers to Charlotte,” Davies said. “The distributed production, with the crew’s cooperation, allowed us to keep our on-site employees safer.”

He said Fox Sports has cast a keen eye on the different strategies other broadcasters and leagues are using, noting, “Everyone has a slightly different take: the MLS had virtual Zoom windows, the NBA has live fan feeds on LED boards and then there were [KBO] baseball games with stuffed animals—some have been using different levels of crowd audio, some have not.”

Oddly enough, someone who had been thinking about supplemental sound for more than 10 years guided Fox Sports’ new approach to the sounds of the game.

“When COVID-19 started, I got a phone call from Fred Vogler, an audio engineer who runs an L.A.-based sonofans. He had worked with Pete Carroll when he was head coach at USC,” he said. “Fred would go to different PAC 12 stadiums and record crowd noise so the team could get a flavor of what playing their opponents on the road was like.”

Fox ended up hiring Vogler and his team “to work with us on MLS, MLB and even boxing, which has never been done with audio,” Davies said. “It’s old school, because there is nothing tied into a data feed. It’s simply someone watching the game and orchestrating the crowd reaction based on what it would normally do. It’s almost like they’re musically ‘scoring’ the game with the crowd.”

SOUND FROM ALL AROUND

For Vogler, the union with Fox Sports is a great example of the power of persistence. “We suddenly have sporting events with no one in the stands, so we’re using live recordings of baseball crowds,” he said.

“We have layers of sounds, as well,” Vogler said. “For broadcasts, our crew of four uses a left-right front and left-right rear mics to get a quadrophonic atmosphere that gives us almost the usual amount of crowd noise. The idea is to have an operator who loves baseball and knows what reactions come at certain points, and give them access so they can react at the right time with the right sounds.

sonofans’ “focus is to create a dynamic bed of sounds that can increase in level with the varying intensities of the game,” he said, via the MADI protocol and trigger pads, plus hybrid software packages (some propriety) “that allow us to access hundreds of files ranging from cheers to clapping to boos—and up to about 30 variations of each.

“You can also hit all three at once, which is often just as a crowd would respond at a game,” Vogler said.

It’s also important to know that a typical non-COVID-19 fan base sounds completely different in each sport. “We’ve also done some MLS matches and they were a hoot,” he said. “Soccer fans have their own chants and cheer to drum beats that provide the crucial pulse of a match; and boxing crowds are aggressive; you can hear their intensity. They have a staccato approach, with tight, percussive voices.”

At Silver Spoon Animation in Brooklyn, N.Y., Executive Producer Laura Herzing and her crew are providing virtual crowds and on-screen graphics via a custom platform called “Crowded” which incorporates Unreal Engine and Pixototte, which enables real-time compositing via a live camera feed and tracking data that is live-composited into the crowd shots.

Herzing said Silver Spoon started working with Fox Sports on three MLB games on July 25 and has worked on a few games a week since; like Vogler, she also noted that such an approach wasn’t needed until this season.

“What we’re doing is similar to using elements of video games in broadcasts,” she said. “Unreal is widely used in the gaming industry, so what we basically did was take that technology and use it another way, for real-time rendering and in the broadcast. We don’t want to trick the viewers, but we want to lend the usual atmosphere they find at the ballpark.”

She and Vogler both appreciate the progressive approach they find working with Fox Sports, which “exhibits an edge when it comes to experimentation,” she said. Vogler agreed, adding, “Most sports broadcasters are just using field mics [to air] the sounds from the empty ballpark. Not Fox Sports.”

Davies shared praise as well, saying companies like sonofans and Silver Spoon “are creating a cottage industry and have emerged as leaders.”

LIVE AND VIRTUAL COUNTERPARTS

Videogaming professionals are not surprised at this sudden melding of two seemingly different worlds.

“This really provides an in-depth look at how closely both live sports and their virtual counterparts are,” said Trevor Williams, CEO of esports events company Capitol Underground in Washington, D.C., “Games like 2K, Madden, FIFA and MLB are constantly trying to create immersive worlds that replicate their live-action counterparts, so when the major [sports] leagues take a play out of the gaming playbook, it doesn’t strike me as shocking.”

Those words were echoed by William Collis, co-founder of Boston-based Oxygen Esports and author of “The Book of Esports.” “I don’t think what’s happening now is any different than what’s happened over time with instant replay, enhanced graphics and other augmentations of sports broadcasts, like the down lines appearing on screen in football,” he said, “so why shouldn’t this trend continue with borrowing from video games?”

Collis offered an example from recent Summer Olympics broadcasts. They “were already enhancing and remixing the sound for rowing,” he said, “for which it’s virtually impossible to acquire broadcast-quality audio.”

Also noting the burgeoning popularity of Statcast, he said, “What separates a video game from the TV broadcast is the interactivity, so it makes sense to incorporate elements from video games to make broadcasts more interesting.”

“What this is about,” said Collis, “is two similar industries evolving their broadcasts. And sometimes with a powerful video game engine and the best software, it’s hard to tell if a video game broadcast on TV is actually a real game or not.”

Such innovation often involves risk, but typically not those of the health variety. Davies reiterated that Fox Sports is bringing its viewers back toward as normal an experience as safely as possible.

That includes the basic masks, sanitizers “and spacing the crew in the truck,” he said, with UV light technology on hand to sanitize the truck’s surfaces “and anything else lying around.”

Of course, the protocols make everyone’s job more difficult. “It takes 100% more time to get the show on the air. You can’t crowd elevators, for instance, and the buffets are over for now; everyone gets a box lunch,” he said.

However, the changes haven’t been all disruptive. Davies thinks much of what Fox Sports is doing will continue post-COVID-19, but in a more expedient fashion.

“Technology has sped up,” he said.

Mark R. Smith has covered the media industry for a variety of industry publications, with his articles for TV Technology often focusing on sports. He’s written numerous stories about all of the major U.S. sports leagues.

Based in the Baltimore-Washington area, the byline of Smith, who has also served as the long-time editor-in-chief for The Business Monthly, Columbia, Md., initially appeared in TV Technology and in another Futurenet publication, Mix, in the late ’90s. His work has also appeared in numerous other publications.