Stainless Continues 300-Year-Old Tradition

(This is the eighth in a series of articles spotlighting broadcasting industry manufacturers that continue to produce their products on American soil with American labor.)

PINE FORGE, PA. Pine Forge isn't exactly a bustling metropolis. In fact, it even baffled my new GPS unit, and as I followed the narrow road past the small streams and stone houses on the way to the Stainless LLC tower manufacturing facility here, I silently thanked the company's president, Don Doty, for sending me directions.

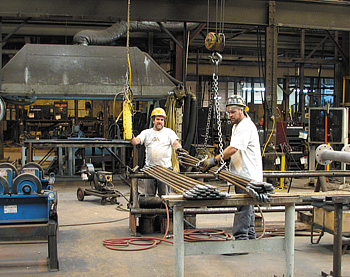

Production workers use one on several overhead cranes at the Stainless plant to move heavy tower components. In this part of the world, the roads have evolved from trails and ox paths. They would never be mistaken for part of the Interstate highway system.

The Stainless building, while close to the road, is partially obscured by a small rise and some trees. I'd almost passed it before I noticed the small "Stainless" and "Pine Forge" signs attached.

In this series, I've been searching out traditionally American businesses that deliver products to the broadcasting industry and it didn't take long to find out that Stainless is deeply rooted in everything that's Americana.

THREE CENTURIES OF IRON AND STEEL

First off, the region in which the Stainless manufacturing operation is located has been involved in iron or steel working in one way or another for nearly to 300 years. Long before there was a United States of America, iron ore deposits were discovered near here and in about 1715, land was purchased from William Penn for creation of the first forge operation in the colony of Pennsylvania.

According to local history, in just a few years the forge operator, Thomas Rutter, was producing iron of high quality.

Rutter built several iron producing operations in the region, the last of these being Pine Forge in 1725.

Musket barrels were produced here to assist the Revolutionary War effort, and during the War Between the States, Pine Forge iron was used to build locomotives for supplying Union troops. Deck plate for iron ships used in the Spanish-American war came from here.

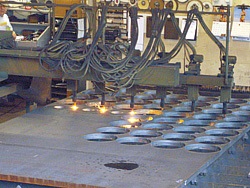

Six computer-controlled plasma torches make short work of creating precision tower components from 2-inch thick steel plate. In 1880 the original forge was relocated a few thousand yards from its initial site to take advantage of a new rail line and reduce dependence upon ox and mule teams to ship product.

This is the site of the Stainless tower operation today.

Steel production continued through World War II, but a fire in the late 1940s burned through half of the 1880 structure and severely curtailed iron and steel production.

The era ended altogether when what was left of the building was purchased by Walter Guzewicz, the founder of Stainless towers. Guzewicz had a hunch that the post-war radio and television boom just might result in a demand for antenna towers, and established his company in Philadelphia in 1947.

During my tour, Doty pointed out portions of the original building that were not damaged by the fire and are still a part of the structure after more than 120 years.

Creating antenna towers is a very specialized business, with only a handful of players—even in America. Stainless LLC is one of these and is responsible for keeping the antennas of a large number of U.S. television and radio stations very high up in the air. To date, the company has constructed more than 7,500 towers, with most of them produced at this 21-acre facility.

My tour of the Pine Forge facility was unlike that at any other manufacturer visited in this series—the plant is devoid of any automatic surface mount parts pickers and placers, wave soldering machines, conveyer belts, clean rooms, or automated testing and repair facilities.

Don Doty, Stainless LLC president, views the growing group of components that will eventually become part of a new candelabra in Florida. Stainless LLC is a hardhat environment in the strictest sense. All workers and visitors are required to don and wear hardhats upon entering. Protective eyeware is a must and there are several dispensers for earplugs to attenuate the noise level in some areas of the plant.

The main floor of the operation is a maze of cutting, machining and welding operations.

IT CUTS, PUNCHES AND IMPRINTS

One side of the building is home to a gigantic "Anglematic" machine, whose name seems to suggest that it could be an extremely heavy duty variant of the popular "Veg-o-matic." However, this baby doesn't cut, slice and dice garden vegetables; it feeds, indexes, punches holes, cuts and imprints alphanumeric manufacturing codes on very sizable hunks of hardened steel.

"The Anglematic is just one of a half dozen in the country," Doty said. "It was installed here in 1986 and can cut three different sized holes in thick steel in one operation. It really spits 'em out."

IDENTIFICATION SYSTEM

Doty explained that the alphanumeric stamping operation the machine performs provides a unique identification number for virtually every component of the towers the company builds. This ensures that erection crews cannot mislocate any of the hundreds or thousands of pieces shipped to the job site.

Giant tower members are stacked and racked all over this 49,000 square-foot building. They create a maze that must be navigated through in order to view all of the fabrication operations under way.

The next stop on the tour is a large multitorch plasma cutter. It operates from templates and can effortlessly burn intricately shaped patterns in four-inch thick steel to create specialized and essential tower components.

Silent against the noise from other fabrication operations, a system of overhead cranes effortlessly moves tower components weighing thousands of pounds from one fabrication area to another.

A Stainless worker uses one of the company's many welders to fabricate a tower sub-assembly. "Some of the earlier cranes we had used DC motors and controllers dating back to the turn of the last century," Doty said. "They were used with a very large motor-generator and were still working quite well when they were replaced for safety upgrading purposes in the 1960s."

WELDERS EVERYWHERE

On first appearance it appears that Stainless has cornered the market on welding machines; Doty says that at last count the number totaled around 30. Both Lincoln and Miller models were very well represented. "Actually, we don't do much stick welding anymore," said Charlie Leinbach, plant manager. "We've gone mostly to MIG [metal inert gas] and are going through 1,680 pounds of welding wire every two months now."

This number compares with the 2 million pounds of steel that passes through the Pine Forge factory every year.

Nearly 450 tons of this year's output is neatly assembled in an outdoor staging area. It's scheduled soon to be shipped to Florida where it will be assembled into a 1,000-foot tall candelabra array that will support six television antennas.

"There's one member there that weighs 10 tons alone," Doty said as we strolled past the growing pile of tower components. "We're set up to handle multiple projects here. In addition to the Florida candelabra, we're also working on a new tower for WVIA-TV in Scranton. It's just about ready to ship."

Doty mentions that there also an order in the works for a new tower for Little Rock's KATV. The station lost their 2,000-footer in an accident last January.

Our next stop is a smaller building at the far end of the property, with contents would make a lot of hardware store owners envious. This is where Stainless stores its enormous stock of bolts, nuts and other fastening components.

"We make a lot of this hardware stuff ourselves," said Doty as he pulled some large representative U-bolts from a bin in the storeroom. "Actually, we go through several thousand of these (U-bolts) in just a few months, so we need to maintain a large inventory."

This remark is amplified as we returned to the outdoor lot and a very large stack of raw steel pieces waiting their turn to be shaped into legs, brackets, flanges, platforms, feet and other components of the tall tower trade.

NO GETTING AWAY FROM STEEL

"We have a million pounds of raw steel sitting out here," said Doty. "Each piece is assigned a number and marked. We can track any piece back through the metal's original processing—its date of manufacture, batch number, heat treatment—we can tell you everything about it."

When asked about the steel's origin, Doty was quick to respond that it was all of American origin, as is everything used in constructing the towers.

"All of the steel that Stainless uses is manufactured here in the United States," he said. "The only time this wasn't done was during the mid-1980s and failure of some important steel mills in this country."

Doty noted that Stainless is very self-sufficient, contracting out only the galvanizing of tower components to nearby firms.

The talk about galvanization leads to a question about the origin of the company's name—Stainless. Doty explained that stainless steel is not used in tower construction. The name actually derives from an earlier venture involving the manufacture of boating equipment.

AMERICAN MADE

As this series of articles is devoted to the manufacturers who have kept their factory addresses right here in the good old USA, you might think this "made in America" principle would be a no-brainer for towers. There's a lot of steel in your average tower, no matter how short or tall, and overseas shipping charges would appear to offset any cheaper steel and labor costs. However Doty said that at one time, some big towers were imported into America from at least one other foreign land.

"They stopped that some time ago," Doty said. "On the other hand, we've done a good business of supplying towers to foreign broadcasters."

At last count, Stainless had more than 7,500 towers in 100 countries.

"More than 50 percent of U.S. tall towers are Stainless," Doty said. "Actually in every major market, more than half are Stainless."

As we return to the main building, a large flatbed truck loaded with large steel pieces heads for the plant gate. It's just another of the countless thousands of similar loads that have moved through these parts during the last three centuries or so.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

James E. O’Neal has more than 50 years of experience in the broadcast arena, serving for nearly 37 years as a television broadcast engineer and, following his retirement from that field in 2005, moving into journalism as technology editor for TV Technology for almost the next decade. He continues to provide content for this publication, as well as sister publication Radio World, and others. He authored the chapter on HF shortwave radio for the 11th Edition of the NAB Engineering Handbook, and serves as editor-in-chief of the IEEE’s Broadcast Technology publication, and as associate editor of the SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. He is a SMPTE Life Fellow, and a Life Member of the IEEE and the SBE.