Switcher Vendors Eye IP With Caution

OTTAWA, ONTARIO—Yes, IP is making its way into the video production chain; and yes, IP-based equipment can deliver a lot more signals (over Ethernet) and switching options than SDI-over-coax can. But this doesn’t mean that switcher manufacturers are transforming their switchers into IP-centric machines—because they’re not. Instead, vendors are moving to include IP-capable I/O signal processing cards so that their products can work with SDI and IP-based signal streams.

“No matter what form the incoming signal originates in, it is baseband video once the signal enters the actual mixing/switching section of the production switcher,” said Greg Huttie, vice president for switching products at Grass Valley. Conversion from and into various signal carriage formats—such as SMPTE’s 2022-6:2012 standard that specifies a way to send uncompressed high bitrate media signals over IP networks—is handled before (input) and after (output) the mixing/switching stage.

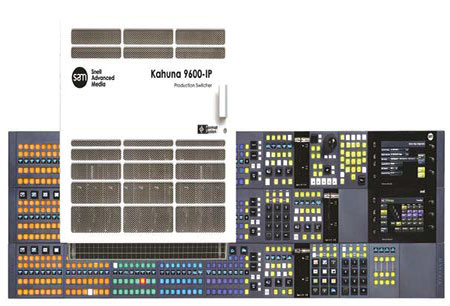

At the 2015 IBC Show, SAM launched the Kahuna IP production switcher range at IBC, which includes a full complement of IP inputs and outputs.

ISLANDS IN THE PRODUCTION STREAM

Admittedly, today’s switchers do exponentially more than their predecessors ever could, thanks to the advent of digital technology that supports far more channels, far more functions, and incorporates previously separate capabilities such as graphics and clip storage. Nevertheless, video switchers are still “islands” in the production stream. All other elements (cameras, routers, and media servers) are connected via bridges of copper and glass, with I/O card-based signal and format converters standing in the middle as intermediaries.

The “island model” allows switcher manufacturers to serve new I/O formats such as IP, because they have to develop new plug-in I/O cards to convert the signals to baseband (and out again). “This lets us keep our products flexible,” said Deon Le-Cointe, product marketing manager for IP live marketing solutions with Sony Electronics Professional Solutions of America. “We can provide our customers with hybrid switchers that handle SDI and IP, and whose mix of SDI/IP I/O cards can be altered as needed.”

This type of arrangement means that switchers aren’t hostage to specific video formats and signal carriage formats, according to Nigel Spratling, marketing product manager for communications and switchers at Ross Video. “This lets us be ‘technology agnostic’, meaning that our switchers aren’t tied to any proprietary formats,” he said.

One exception to this “island rule” is NewTek’s family of IP-based TriCaster video switchers. “We’ve been working in an IP-connected world since the first TriCaster was re-leased 10 years ago,” said Dr. Andrew Cross, NewTek’s president/CTO. “As a result, our video switchers connect directly to other devices and locations via Ethernet, because IP is a natural fit for us.”

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

In September, the company announced the launch of NewTek NDI that, according to Cross, is a new open standard for live production IP workflows over Ethernet networks. Cross adds that the company will be taking steps shortly to make it easier for vendors to collaborate on the standard. “We’re going to be releasing tools that take NDI and attach it to any of the commodity capture cards out there,” he said.

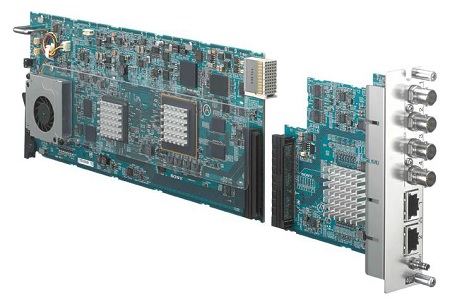

At the 2015 NAB Show, Sony conducted a demo that featured a single 40 GbE fiber-optic Ethernet cable transmitting multiple 4K and HD video streams from the camera area at Sony’s booth. Video streams transmitted by cameras were converted from SDI to IP by Sony’s NXL-FR318 Signal Processing Unit—equipped with this NXLK-IP40T SDI-IP Converter Board.

CODEC CONUNDRUM

Although SMPTE 2022-6:2012 is an industry-recognized video-over-IP transmission standard—and is supported by switcher manufacturers—it is regarded as a transitory solution to the video-over-IP problem. This is why some video equipment manufacturers have developed their own video-over-IP transport standards such as NewTek NDI.

At the 2015 NAB Show, Evertz took a different path, introducing ASPEN, which Mo Goyal, director of product marketing for the Burlington, Ont.-based provider of video processing and transport technology, described as “completely open.”

“The key benefit of ASPEN [over SMPTE 2022-6] is the separation of video, audio, and ancillary data [or metadata] into individual multicast flows,” he said. “These individual multicast flows provide immediate flexibility that allow broadcasters to choose specific video, audio and data from various sources and send them to destinations like the production switcher.

“ASPEN also provides additional benefits as it includes the use of existing MPEG-2 Transport Streams, which provide information to identify streams and timing,” Goya continued. “The advantage of using MPEG-2 TS is that its familiar to most broadcasters as it’s used for contribution and distribution transport of video/audio signals. The ASPEN framework is also future-proof. Today it maps uncompressed UHD/3G/HD/SD signals into TS, however it has provisions to add other formats [compressed or uncompressed]. This protects the broadcaster’s investment in the IP infrastructure.”

Other companies are looking to the Video Services Forum, an industry-driven video networking technologies group and its efforts to devise a new, better intra-facility video-over-IP standard for sending uncompressed video over IP (see “New Standard for Studio Video Over IP Approved,” November 2015).

At SAM (formerly Snell Quantel), the company’s goal is to try and avoid costly, royalty-required codecs that come from manufacturers, according to Tim Felstead, head of product marketing at the U.K. company. “This is why we would rather follow the standards developed by the VSF and its royalty-free supporters,” he said.

The lack of an accepted high-performance video-over-IP standard forces switcher manufacturers to take a cautious approach to the IP transition. They cannot risk incorporating IP functionality into their core mixing/switching functions, for fear that whatever video-over-IP standard they implement might soon prove as dead as HDV.

This necessary caution hampers the full deployment of IP functionality in video production. It also weakens the motivation for broadcasters to make the move to IP now, even though the move would allow them to use lower-cost, off-the-shelf IP data routers in broadcast facilities. “If all we’re trying to do is replace SDI coax with CAT-6, then I don’t think we’re making a truly compelling case for IP in broadcast production,” said Kevin Prince, the new president and CEO of Broadcast Pix in Billerica, Mass.

Cross echoes Prince’s concerns. “If all you are trying to do is move uncompressed video over IP, then it is actually more expensive to use Ethernet versus IP,” he said. “This is why we use compression to carry up to 16 HD channels over a single Gigabit Ethernet connection. Without compression, you couldn’t even get one 1080i channel down this pipeline.”

Until the video-over-IP high performance standard conundrum is resolved, broadcasters and video producers can expect production switchers to remain consistent in their form factors, sizes, and weights. There is simply no reason for switcher manufacturers to make radical changes based on an adoption of new technology: They are safer working with what they have now, while constantly refining existing features and expanding their systems’ capabilities.

Even when this debate is finally settled, Cross doesn’t expect the switcher interface to change radically. “It has taken 40 to 50 years for video switchers to develop and then hone this interface,” he said. “Like a modern music DJ’s digital mixer that mimics using two analog LP turntables as cueing surfaces, I don’t expect tomorrow’s switchers to reject the time-proven interface of today.”

James Careless is an award-winning journalist who has written for TV Technology since the 1990s. He has covered HDTV from the days of the six competing HDTV formats that led to the 1993 Grand Alliance, and onwards through ATSC 3.0 and OTT. He also writes for Radio World, along with other publications in aerospace, defense, public safety, streaming media, plus the amusement park industry for something different.