Tom Foreman: Tech Must Always Serve Storytelling

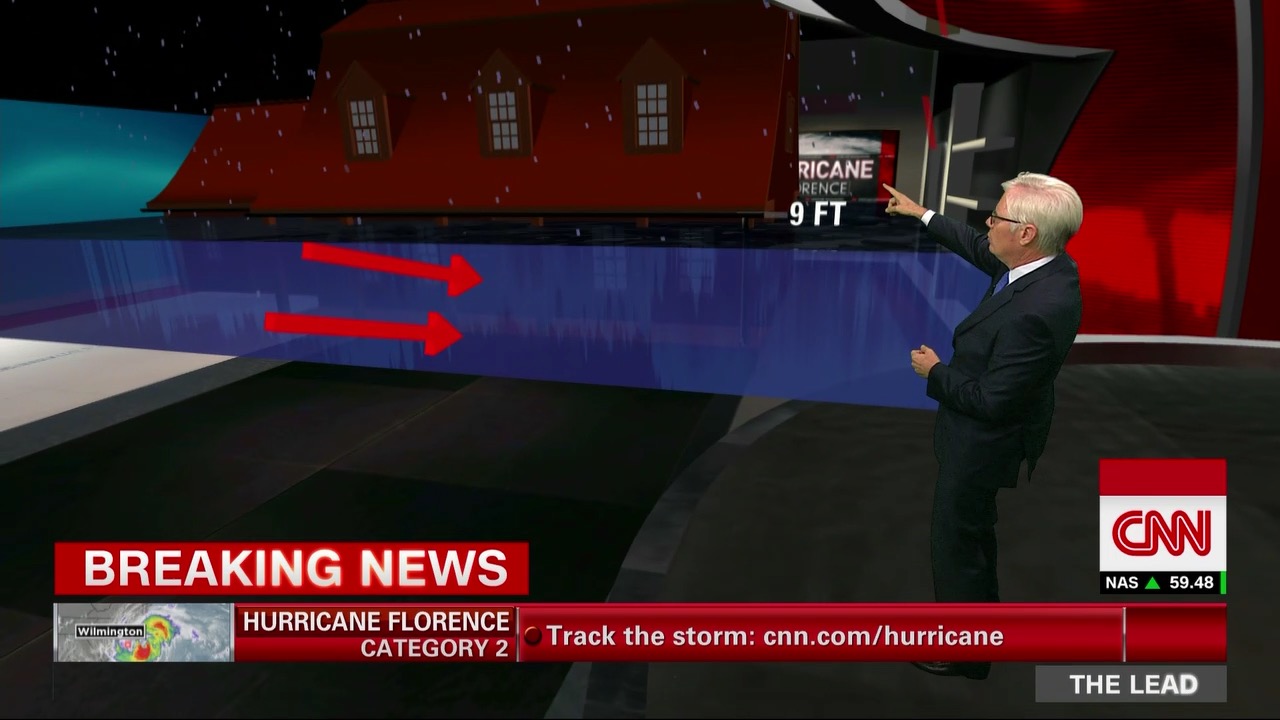

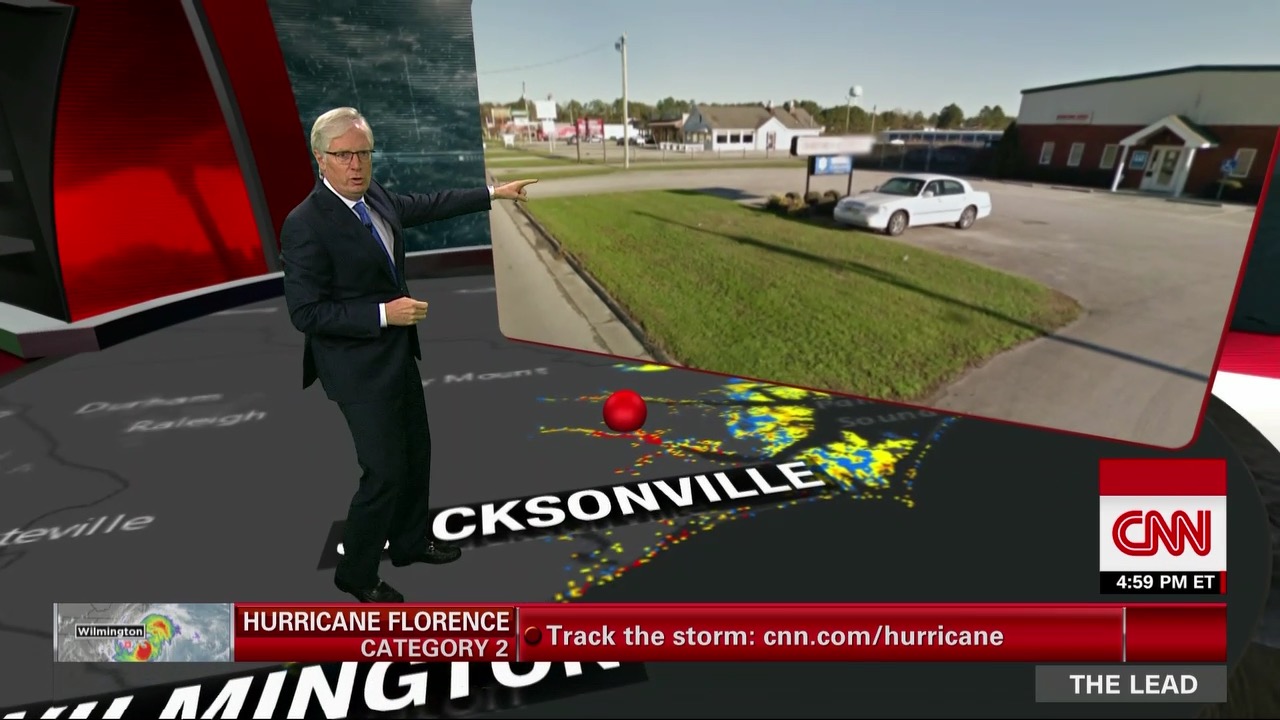

You've seen him on CNN stalking around a virtual environment and interacting with graphical representations of the SCOTUS process, North Korean missiles or Royal Thai Navy SEAL divers. Tom Foreman has established much of the network's work beyond video, playing a key role in the development and use of an immersive, 3D virtual studio that takes viewers to space to study satellites, onto distant battlefields to promote understanding of dangerous conflicts and down deep into the data of presidential elections.

Foreman will be a keynote speaker at Government Video Expo 2018. He spoke with Managing Director of Content Paul McLane for Government Video.

Government Video: You've done a lot of work in broadcast news with technology you've described as "going beyond video." What exactly does that mean?

Tom Foreman: We now have tools that allow us to visualize concepts that previously were not visual. We can turn data, we can turn ideas, we can turn trends, into interactive, touchable graphics, with which we can tell a story that adds clarity to our understanding of an increasingly complex world.

Previously, there were economic trends, crime trends, security trends that were difficult to visualize. But if you can turn it into an environment that you can stand next to, it helps people, who are visual creatures, to see what we're talking about.

GV: How did you become involved with the virtual studio?

Foreman: Hurricane Katrina was the birth of a lot of this. I had a deep and long understanding of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast from having worked there in traditional journalism — doing beautiful pictures, explanatory pictures and reports. And yet Katrina brought such a scope of disaster that no one picture could do it justice. Even a collection of pictures could not do it justice. You needed the giant view that we could bring through a graphic treatment. What we were using at the time was a giant wall-based projection of Google Earth, which I was controlling with a mouse in my hand, I was controlling it on set and we were flying in and out.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The real value, though, came from the combination of traditional on-the-ground reporting and photography video that supported it, then using this as a high-tech frame that let us add the meaning that said, "Okay, I just showed you a picture of a church halfway underwater. That matters because this is where that church is; and down the street is this school, and down the street is this government building, and over here is the streetcar line." It gave a context.

We did the same thing after the earthquake in Haiti. We were able to show, not only where the damage was, but by widening out and using some of these tools to show satellite images before and after, we were able to analyze road blockages and say why it was so hard for aid to get to people. The Army asked if they could get copies of our images, because they were having trouble figuring out how to get things to people, and our analysis with the satellite images worked for them.

GV: Why aren't more people doing this in such a visual world? Is it cost?

Foreman: I don't think it's cost, it's understanding. This is a very high-tech tool for a very traditional and old-fashioned process: storytelling. A lot of people mistakenly think that this is whiz-bang, it's all about amazing graphics and immersive graphics; that is not the case at all.

Almost everything we produce begins as simple paper-and-pen drawings on my desk, where our team gathers around, and we draw it; and as we draw it, we're saying, “What is the story? What is it we're trying to convey?”

I think one of the reasons people don't do it — or do it effectively — is they compartmentalize it. "Well, the graphics department will create this; and the show production team will create this; and we'll bring in a reporter at the last minute and plug them in." That absolutely does not work. You have to have the full team involved from beginning to end.

GV: Is there a risk that these tools could come to be used in place of live reporting, rather than to complement it?

Foreman: I don't think so, because everything we do is grounded in traditional journalism. Everything we do is grounded in finding actual facts. In fact, we steer away from doing it when we can get access that shows us what we want.

GV: You've used this technology for so many interesting projects. Are there two or three that particularly stand out?

Foreman: This has been tremendously helpful in giving a sense of scale, when we've dealt with natural disasters; in giving a sense of proximity, when we've dealt with war situations; and in helping us peek into places where we can't readily look.

As we've analyzed the North Korean missile and nuclear program, it's been tremendously useful to show exactly how much progress they're making — and what they still have not yet accomplished. Missiles involve almost incomprehensible distances and speed and force; this allows us to depict that.

In the search for the missing Malaysian airplane, this was an enormously useful tool. When you say to somebody "five thousand square miles of ocean," most people have no idea what that looks like. If somebody talks about something being 1,500 feet underwater, they don't really understand what that means either. We're able to depict that in ways that make sense.

GV: Look ahead five years, how is our experience of watching content going to change further?

Foreman: You see sports embracing this a little bit. Sports can do that in part because you're always talking about a very defined situation. The football field is this size, and there are two teams, and they play this long. Basketball, field hockey, arena, whatever.

We're going to see a lot more of this embraced, not just by news organizations but by anyone who's in the business of trying to tell a story. Because frankly the world we live in today is endlessly complex compared to the world we lived in 50 years ago. You can wake up in the morning and get an email from a friend in Indonesia, respond to a phone call from your office down the street, see photographs from a family member who's three time zones away, and search back 20 years for records of information that you might need that day. You are traveling time and space every minute, much more than we used to. That requires a new kind of understanding of that information.

We can't make our brains evolve that quickly, so what we have to do is have tools that allow our brains, as they are, to connect with this new reality.

GV: What about artificial intelligence, 4K, other technical areas?

Foreman: Willa Cather once wrote that art should simplify, that it's about simplifying ideas and making them understandable. All these technological things—the quality of video; the immersive nature of some of these systems—I think that's going to continue. The real secret here, for those who want to thrive in this environment, is to recognize them for just what they are: These are tools for a simple process of understanding. If you let it become about the tools, then it becomes more noise, more clutter that doesn't help you understand the world.

This world that we're going into is not for the faint of heart. There are huge challenges to making sure this technology serves us. But the rewards for doing that are absolutely immense.

Many years ago, when I was a very young person, I did a big, a big magic show with flying doves and floating ladies and fireballs and the whole thing. That has been enormously useful to me. The whole purpose of a magic show is knowing what's really going on, which can be incredibly complex. And yet remembering what the audience sees — and knowing you have to let them come along in the story, in a way that works for them — that's what we're doing here.

When I'm in the virtual environment, there is rarely a gesture or a step or a turn that is not carefully constrained by the technology that I'm surrounded by. Only if you do that properly does it appear real, in a virtual sense; and only then can the technology disappear and the understanding come through.

Key Takeaways

Who? Tom Foreman of CNN is a featured keynoter at Government Video Expo on Wednesday, Nov. 28, in the session "From the 'Situation Room' to the Thailand Caves — Today's Evolving Journalism”

Why? New technology is helping media professionals tell stories more effectively by leveraging "the one thing humans are really good at: visual interpretation."