TV in 2024: Change to the Business Further Accelerates

From rapidly evolving viewer tastes to a transformative election, change is now a constant for an already disrupted industry

In the parlance of best-selling sci-fi novel turned Netflix series “Three Body Problem,” you have to think long and hard for the last time the television business enjoyed a “stable era.”

Certainly, 2024 saw what seems like a never-ending chain of disruption continue: Hollywood conglomerates and streaming companies had to manage major content pipeline disruption from the previous year’s talent-guild strikes; streaming continued to eat away at viewership share for linear platforms, while big streaming companies gobbled away more life blood, live sports, from the content ecosystem; and now, with Republicans sweeping into federal power, come a whole new mind-blowing array of M&A possibilities.

‘DNA Level’ Change

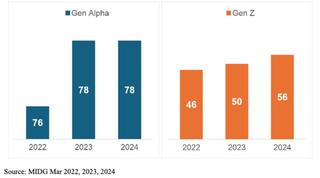

In fact, the transformation of the video business is now occurring on a DNA level, with many denizens beginning to ponder what “television” is in the first place. In June, for example, research company Maverix Insights & Strategy published data suggesting that “Gen Alpha” (roughly defined as those born between 2013 and 2024) devotes 78% of its screen time to watching video distributed on social media.

The youngest generations of viewers never had a “cord” to cut. And rather than “Netflix and chill,” they’re choosing an entirely new form of video entertainment as their staple choice of consumption.

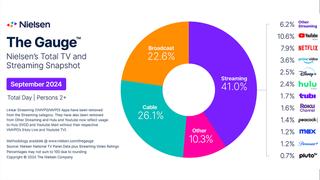

The movement toward social video is more broadly apparent in the monthly U.S. viewership share reports published by Nielsen. In September, the research company’s The Gauge showed that YouTube consumed 10.6% of all living room viewing of “television” in American homes. That’s up from 9% in September 2023 and 8% in September 2022.

Overall, Nielsen suggests that streaming accounted for 41% of American TV consumption in September 2024, up from 37.5% in 2023 and 37% in 2022.

Across the board, Hollywood conglomerates and Silicon Valley technology companies reported major increases in streaming revenue. For example, the world’s biggest streaming company, Netflix, reported a 15% increase in third-quarter revenue to $9.825 billion, while growing its global subscriber base by 14.4% year over year to 282.72 million. Netflix also reported an all-time high in free cash flow in Q3 of $2.194 billion.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Traditional media companies felt the lift, too. Paramount Global, for example, saw a 10% sales increase in Q3 from direct-to-consumer streaming platforms including Paramount+, with subscription streaming platform’s user base increasing by 3.5 million to 72 million paying customers. Paramount said it’ll still lose money on streaming in 2024 but will start turning a profit next year.

Over at Warner Bros. Discovery, meanwhile, the DTC segment—which includes subscription video-on-demand platform Max—saw sales rise 8% in the third quarter to $2.634 billion. Max now has 110 million streaming subscribers worldwide now.

And Disney saw its streaming operation deliver a $321 million profit from July - September vs. a $387 million loss for the same period of 2023.

The ‘Strike Hangover’

At least for the traditional Hollywood entertainment giants, however, the green shoots of streaming were not enough in 2024 to offset the declines of linear revenue channels.

For one, the crippling Hollywood guild strikes of summer 2023 continued to take their toll on revenue generation well into 2024.

Despite its streaming success with not just Paramount+, but also free ad-supported streamer (FAST) Pluto TV, Paramount Global saw its third-quarter revenue drop 6% to $6.73 billion, a result it directly attributed to the content pipeline slowdown caused by the strikes. Paramount management said the “hangover” of the strikes was felt across its CBS Television Network, its cable channel and its theatrical movie business.

Across the board, Hollywood conglomerates and Silicon Valley technology companies reported major increases in streaming revenue.”

Streaming just isn’t enough of a business yet to offset these linear declines, particularly in the moribund “basic cable networks” business.” WBD reported flat revenue growth to $7.662 billion from its DTC efforts through the first nine months of 2024. The company’s linear networks generated around twice as much revenue over that same period, $15.407 billion, but saw a decline of 5% YoY.

The future for these media networks isn’t necessarily looking brighter ahead. WBD’s TNT, for example, will lose its NBA rights starting in 2025, with Amazon muscling its way into the league’s national TV partnership group with a $1.8 billion-a-season deal … and muscling WBD out in the process.

Any Hope for Traditional?

The entry of Amazon, Apple and Netflix into the live sports business threatens to further erode media company linear networks in the years to come.

For operators and bundlers of linear TV networks, and everyone connected to them, there was some good news in the latter part of 2024 suggesting that cord-cutting might actually be slowing down a little. The three biggest publicly traded pay TV operators (Charter Communications, Comcast and Dish Network) each reported declines in Q3 in the number of subscribers quitting their services.

And the pay TV industry is finally responding in a meaningful way to changes to video subscriber consumption habits that have been rapidly occurring for a decade.

Charter, for example, signed a series of pay TV carriage deals in 2024 with WBD, NBCUniversal, Paramount and other media companies that allow it to bundle these media conglomerates’ SVOD services into pay TV packages at no additional cost. In 2025, once all these services get integrated into Charter’s delivery system, the cable company said it will be delivering $80 a month of SVOD services to subscribers of its most popular video tier, the $125-a-month Spectrum TV Select+, at no additional cost.

Charter has received numerous shoutouts across the video business lauding it for creating a value proposition that could actually cause customers to reconnect the cord.

But traditional pay TV distribution remains a challenging business. In November, for instance, Alaska’s biggest cable operator, GCI, announced plans to shut down its pay TV operation in mid-2025. GCI will now offer customers the Xumo streaming platform jointly developed by Comcast and Charter.

Meanwhile, also faced with extinction, the two big satellite TV companies, DirecTV and Dish Network, announced a renewed effort in 2024 to join forces through M&A. Previous attempts to merge had been shut down by regulators, but this time, it was an ill-fated negotiation over how to handle Dish’s significant debt load that ended the engagement. It’s widely believed, however, that if the internal talks hadn’t collapsed, regulators wouldn’t have stood in the way.

A New Regulatory Environment

In fact, moving into 2025, regulators might not stand in the way of much of anything. With former President Donald Trump and the Republican Party sweeping back into power following a convincing Nov. 5 election win, there’s a belief among media titans that the federal government will rapidly shift to a laissez-faire stature on media company dealmaking.

Among Trump’s early appointments was veteran federal regulator Brendan Carr to head up the FCC. Carr has publicly agreed with the incoming administration’s pledge to slash regulations as well as go after Big Tech.

Hoping the new regime modernizes old FCC rules on station ownership, Sinclair Broadcast Group CEO Chris Ripley told investors two days after the election: “We’re very excited about the upcoming regulatory environment. It does feel like a cloud over the industry is lifting here.”

Speaking to investors the same day (Nov. 7) during his company’s Q3 earnings call, WBD CEO David Zaslav remarked, “It’s too early to tell, but it may offer a pace of change and an opportunity for consolidation that may be quite different, that would provide a real positive and accelerated impact on this industry that’s needed.”

Of course, we are indeed “early” following the tumultuous aftermath of the 2024 national election. And Zaslav perhaps simply didn’t remember that former AT&T CEO Randall Stephenson had to sue the U.S. Justice Department in 2017 to clear the purchase of the company Zaslav now runs, then called “Time Warner Inc.,” because Trump, in his first presidential term, wanted a certain Time Warner Inc.-owned cable network he doesn’t particularly favor, CNN, cast out of the deal.