Where No Broadcaster Has Gone Before

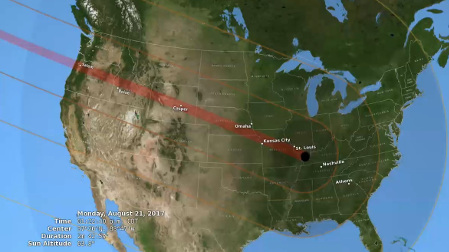

BOZEMAN, MONT.--It starts with a total solar eclipse. But not just any eclipse: The Great American Eclipse.

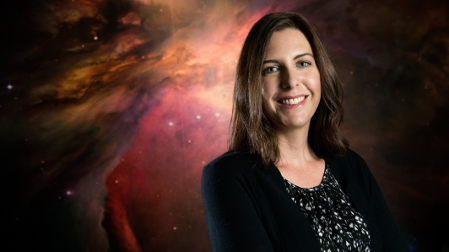

Angela Des Jardins, director of the Montana Space Grant Consortium

When Angela Des Jardins decided to produce the world’s first live streamcast from near-space, a watch-worthy event was a must. And on August 21, the universe is giving her one. The United States has seen total solar eclipses before, but this is the first time in U.S. history that one will only be visible here. As for the rest of the world? They’re welcome to watch online.

In fact, eclipse2017.nasa.gov is hosting 10 different streamcasts eclipse-day. Of the 1 billion unique hits anticipated, NASA predicts half will be for Des Jardins’ livestream. The others are views of the eclipse from the ground, from a high-resolution airplane—angles that, while cool, aren’t broadcasting firsts.

MADE WITH RASPBERRY PI

Like all producers, the next two needs were a project name and money. The name was easy: The Eclipse Ballooning Project, since the cameras shoot from high-altitude balloons. As for money, she simply asked NASA the same question she’d asked herself when the idea came: If Felix Baumgartner can jump out of a balloon from the stratosphere and broadcast that, why can’t we live-broadcast an eclipse from near-space?

The problem, though, as Des Jardins points out is that “[Red Bull] had a $10 million satellite feed truck and system.” No way was NASA going to fund $10 million for an eclipse.

But that was 2012. This is now and a lot has changed. She breaks it down: Red Bull didn’t have the “new technology we have to be able to do this inexpensively and very lightweight.” (To meet FAA requirements, equipment must be under 12 pounds per balloon.)

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

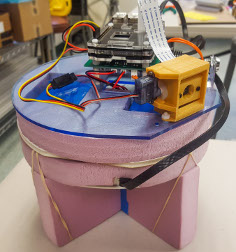

Each balloon will be outfitted with a $30 Raspberry Pi camera board.

“There are really three main technologies that all kind of came together at the right time to even enable this to happen,” Des Jardins continues. “One is the miniaturization of computers like Raspberry Pi.” A Raspberry Pi camera board—with cable—costs $29.95 and weighs 3.4 grams.

Add Arduinos and a 5.8 gigahertz transistor communicating with a ground antenna, and each balloon payload comes to $3,700. Participating universities, like Austin Peay State University (APSU) in Clarksville, Tenn., buy the equipment then NASA reimburses.

Which brings us to Des Jardins’ next need: A camera crew.

GPS COORDINATES

The eclipse starts in Oregon and ends in South Carolina. Des Jardins is director of the Montana Space Grant Consortium, one of 52 members of NASA Space Grant Consortium. While teams don’t have to be based at a space grant college to participate, the consortium did give Des Jardins ready access to volunteers, some of whom had recorded b-roll from balloons before.

A trial balloon was deployed a year before the eclipse.

“We’ve done balloon flights for years,” APSU’s Dr. Justin Oelgoetz says. Last year, students launched a GoPro to grab footage for analyzing water quality. “[For] some things, the GoPro is easier and more appropriate,” he said. GoPros are sturdier, but “if you need to tie a picture to a particular GPS coordinate or if you need it taken through a particular filter, then you really want to do the Raspberry Pi because the Raspberry Pi can read the GPS; it can put that in the metadata for the pictures or in a supplementary file which relates the position to the time.”

Connecting position and time is integral for live-broadcast of a moving target, and points out the next need: A director. Because of the moon’s speed, the eclipse’s totality at greatest duration is just 2 minutes and 40.2 seconds. In broadcasting, two minutes can be a long time. But the balloons—expected to be more than 30 in total—aren’t evenly spaced geographically. Some parts of the path only have one. In Illinois and Kentucky—where the points of greatest duration and greatest eclipse are—15 balloons will launch within a tighter area. So some cameras may capture the best angle for seconds.

Celestial mechanics predict the exact path the eclipse will take, so it’s tempting to run down exact timecodes for switching from one camera to the next. But when you send cameras 100,000 feet in the air, plans change. “Sometimes you hit a violent crosswind,” Oelgoetz says, “so things can get wild for a few minutes.” That’s why APSU puts its camera inside the balloon payload instead of outside. Oelgoetz says NASA’s kits are also secured by “pieces of that foam board they put in house walls as insulation.” Still though, his team’s not taking any chances: “We’ve got duct tape on it.”

DIRECTED BY AN ALGORITHM

Even when the camera makes it up—and stays up—safely, Oelgoetz says something else can go wrong: “Ice. We get ice around the edges of the image sometimes. It depends on the weather [and] mounting.”

So, not that easy to direct after all.

That’s why there is no director. Instead, Des Jardins chose an algorithm. “The main web page will have a map of the U.S. and one main feed that it’s focused on. But you’ll see on the side of the screen little thumbnails of all the video feeds.”

This map shows the eclipse path across the North American continent.

Here we find the only problem Des Jardins has yet to resolve: How does the algorithm choose which camera goes live when? According to Des Jardins, “[T]hat’s based on where the totality is happening at the time... but it’ll also do a quick check of what the quality of the feed is and so it’ll pick who’s in totality or coming up to totality and has a good quality feed.” She then adds a person will supervise control room-style.

Ask Will Jaimeson, though, and you get a different answer. He’s CMO at Stream, the project’s online video platform (OVP). Stream hadn’t planned on a person checking the algorithm’s work; and quality doesn’t weigh into the math. “It’s going to be automatically showing what should be the most viewed or the best content at the time based on view counts as well as identifying exactly where the eclipse is actually over totality,” he said. In other words, Stream’s algorithm crowdsources the stream, “default[ing] to the ones with the highest view counts.”

Of course, Stream will say quality is in the eye of the beholder, as viewers hopefully won’t select poor shots. But this minor discrepancy does show that regardless of whether your production’s in near-space or here on earth, the problem hardest to solve is the same: communication. And Des Jardins has until August 21 to figure that one out.