How Bright Is My Studio?

A method for choosing the right light level

Although it’s an important question, few clients ever ask how bright their new lighting will be. In the hectic job of revamping a studio, such technicalities are usually left up to whoever’s doing the lighting. But because the answer will impact several systems down the line, choosing the right intensity needs to be based on your studio’s particular needs and not randomly picked. Here’s why.

Lighting will affect everything seen in the studio. This broad-ranging impact is why I suggest going through a process to discover exactly how much light is appropriate for the project. Rather than pulling a number out of a hat, I try to find the “Goldilocks” level that’s “Not too bright. Not too dark. Just right!”

Back in the early 1970s, cameras needed a whopping 300 fc (foot-candles) to produce decent pictures. That was bright enough to make you squint, rather than smile for the camera. Over the years, cameras have improved, and lighting levels have dropped a lot. Today, studio levels are a comfortable 45–65 fc. But there’s more to the task than simply picking a number in that range.

Camera Sensitivity Determines Light Intensity

Getting beautiful images requires more than just a correct exposure. Skilled photographers, cinematographers and videographers use a variety of camera techniques in crafting their images. Unless you happen to be a cinematographer as well as a lighting designer, you might not appreciate how much lighting affects the camera image. One particular camera adjustment that’s directly linked with light levels is the aperture (or iris). As we’ll see, this affects more than just the exposure.

In television, we want the viewer’s attention on the stories and the people telling them.”

In television, we want the viewer’s attention on the stories and the people telling them. By controlling which part of the shot is in sharp focus we direct the viewer’s eye to what’s important on the screen. By design we can control that sharp focus through manipulation of the “depth of field.”

Our sense of depth is possible because we have two eyes with overlapping fields of view. Cameras lack this type of binocular vision, called stereopsis, because they only “see” through a single lens. In the absence of stereopsis, a camera can still indicate depth by providing other visual cues for dimension. Depth of field is one such cue; by alternating a sharply focused zone against softer focused areas, our brain subconsciously builds a three-dimensional understanding of the pictured space.

So, how do we create this sense of depth by selecting the right light intensity? The lens adjustment that affects depth of field, as well as regulating how much light reaches the camera’s sensor, is the iris.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Bear with me while I cover what may be familiar ground to you. The iris (or aperture) regulates the light in increments called f-stops. The size of this aperture affects the depth of field through its impact on focus. Without delving into how the “circle of confusion” impacts focus, let’s just note that the smaller the iris opening (higher number f-stop), the greater the depth of field. The lower the f-stop number, the shallower the depth of field.

The photographer Ansel Adams famously used f/64 to get everything in sharp focus for his iconic images of the American West. While that infinite depth of field was appropriate for his scenic images, we don’t want that for our studio shows.

In newscasts or interviews, we want the visual emphasis on the talent. Towards that end, we focus attention on them with a bust shot that’s in sharper focus than the background. That selective focus is achieved by choosing an f-stop that simultaneously provides the depth of field we want and the right amount of light for a good exposure. But which f-stop is that?

My personal choice for the “Goldilocks” f-stop sits between f/2.8 and f/4. That aperture provides an adequate depth of field to keep the anchors in focus, and just the right amount of background softening to suggest some separating distance. That “f/2.8–f/4 split” is the sweet spot where I start the process of determining how much light I need to use.

Light To the F-Stop for Desired Depth of Field

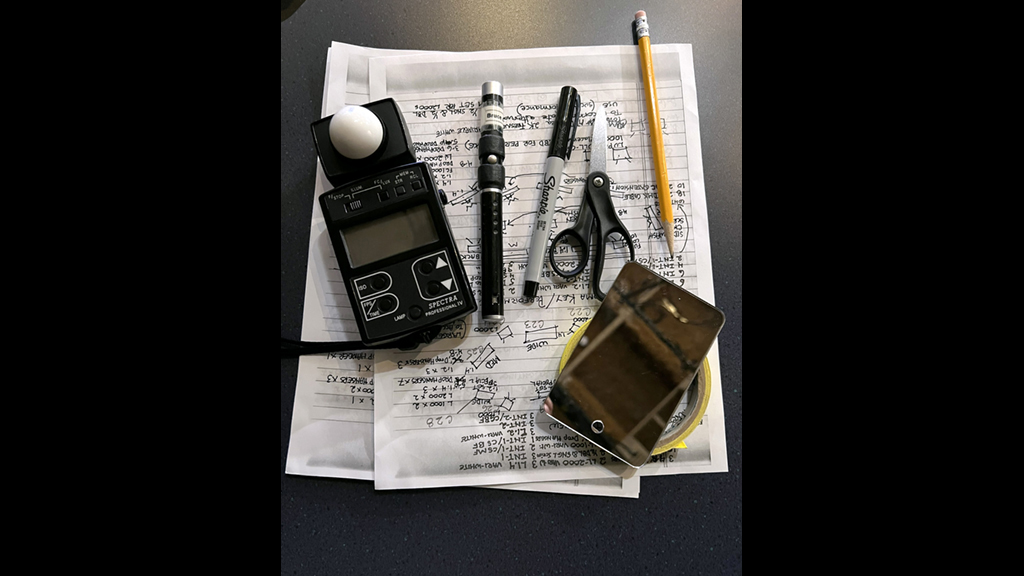

To find out how much light you need for your cameras, frame a shot of the chip chart (with teleprompter to account for the light loss from the mirror) from roughly 8 feet away to approximate the “normal” anchor-to-camera distance.

White-balance with the clear camera filter at whatever color temperature lighting you’re using in your studio. Set the iris to the mark between f/2.8 and f/4. Then, adjust the chip-chart light brightness until the chips fall into their proper levels on a waveform monitor.

Once that’s done, take a light meter reading of the chart intensity from in front of the chart (sphere diffuser, pointing back to the camera lens). Whatever intensity reading you get is the value to use for your lighting positions. For most studio cameras today, it will probably be somewhere between 45 fc and 65 fc.

If the number you get is lower than 45 fc, you may need to make a modification to boost that number higher. This is especially true if your set incorporates video displays, which perform poorly at very low brightness levels. The solution is to rerun the process with the cameras set at a –3 db “gain,” which will nudge the required light level higher.

That’s my process for deciding what the “right” light level is. Neither the intensity nor the f-stop should be arbitrary or accidental in crafting an image. That’s why this process is driven by the choice of f-stop, which is, in turn, based on the depth of field we want.

The “f/2.8–f/4 split” is a subjective choice that I think looks best for most news sets. Your criteria may be different, based on how much (or little) depth of field you want. The process will run the same regardless of which f-stop you choose. The point is to choose by design, rather than haphazardly.

Bruce Aleksander is a lighting designer accomplished in multi-camera Television Production with distinguished awards in Lighting Design and videography. Adept and well-organized to deliver a multi-disciplined approach, yielding creative solutions to difficult problems.