LED Fresnels: A (Somewhat) Different Light by the Same Name

There have always been some trade-offs alongside advances in lighting

Wood carvers will sometimes use chainsaws to “rough in,” but finishing requires more subtle sculpting tools. In lighting, as with other crafts, no single tool is perfect for everything. Coarse or refined, our tools shape the process and impact the results. Tools change and process follows.

When I began using lighting CAD, I wondered how it would affect my design process. After all, working with a keyboard and mouse is very different from drafting with plastic lighting templates and pens. It turned out that the resulting designs still held true to my intent, but the process was certainly different. Any trade-off was a bargain I was happy to make.

There have always been some trade-offs alongside advances. On balance, there was no doubt it was a net gain. As with my old plastic lighting templates, now languishing in storage, I’m never going back.

It’s In the Shadows

While no one wants to backslide from the advances of LED lighting, let’s admit that not all the changes are for the better. These new LED variants work, but they’re not quite the same.

Changes in lighting styles ebb and flow with shifting tastes, but I suspect the current trend towards flatter light is steered as much by our new equipment as by our creative intent. Quite frankly, I miss shadows.

In a medium that’s basically two-dimensional (since the camera has one “eye,” and our screens are flat), a lack of shadows results in fewer three-dimensional visual cues. If our goal is to keep images interesting, shadows are still key. That’s why “hard light” is important.

By tradition, there are two main categories of lights: “Hard light,” which creates highlights and shadows, and “soft light,” which moderates shadows with diffused “ambient” fill. Although that’s a somewhat simplistic explanation, it conveys the idea.

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

The main “hard light” in video studios has been the Fresnel, while “soft light” includes any fixture (or modifying accessory) that imparts a relatively large light-emitting surface. The interplay of these two qualities of light creates a sense of depth through highlights and shadows. Artists refer to this quality of shading as “chiaroscuro.”

A basic soft light is relatively easy to make. Clump together enough LEDs into a panel, and you’ve got a crude soft light. But a proper Fresnel requires a lot more optical design.

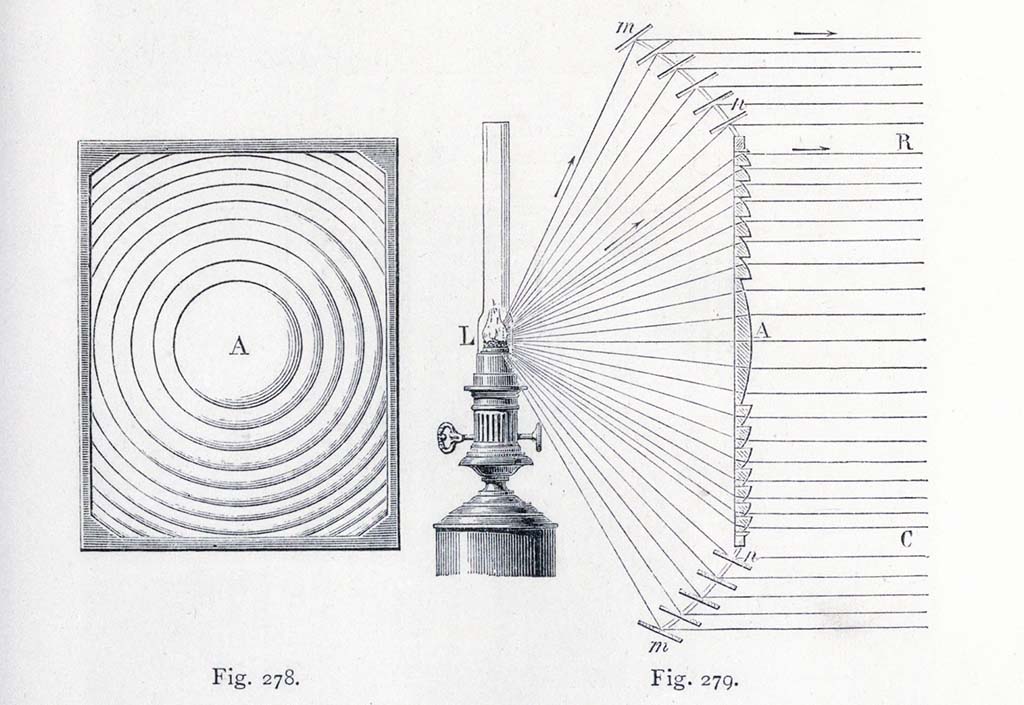

The best of today’s LED Fresnels are quite good, but their beam quality at flood is different than with legacy incandescent Fresnels. That difference lies in the collimation of the beam. Centuries-old designs for lighthouse lanterns worked out this problem based on a single point of radiating light. With the advent of LED, the light propagation behind the lens is different.

The Same, but Different

Many LED Fresnels are more like soft-edge wash lights than their namesake; their barn doors are more useful as glare shields rather than for shaping the beam. The name may be the same, but the tool has changed. For all its advantages, the light from current LED Fresnels isn’t collimated the same. Here’s why.

The compact “luminous capsule” of incandescent and HMI radiates light 360°. Although wasteful from an energy efficiency standpoint, it’s optically useful behind a Fresnel lens. An incandescent lamp at full flood (when the lamp is closer to the lens), allows the light to cover the entire Fresnel lens.

By reaching all the concentric rings that comprise a Fresnel lens, the light is collimated into a larger, organized beam that’s malleable. At the same time, by filling much of the lens, the larger surface area imparts a “wrapping” quality that provides a subtle roll-off in the shadow it casts, which is more flattering to the face. This is why larger Fresnels have been so popular as talent key lights.

That’s [Not] a Wrap

That “wrap” isn’t the same with today’s LED Fresnels.

LED emitters are both larger and more directional compared to the radiant 360-degree “luminous capsule” of incandescent and arc lamps. While more efficient, there’s a tradeoff: When an LED Fresnel is at full flood, the light only engages the very center rings and bull’s eye of the lens. And, because the relative softness of a light source is directly proportional to the size of the light-emitting surface, an LED Fresnel can’t “wrap” the face quite the same way as a legacy Fresnel could.

As a result, LED Fresnels put out a quality of light that is less pliable (because the light is less collimated) and “harder” (because the working surface area of the lens is smaller at flood) than the incandescent version. It’s not the same, but “good enough.”

While no one wants to backslide from the advances of LED lighting, let’s admit that not all the changes are for the better.”

While clever R&D continues to improve these fixtures with the use of secondary optics (as with the ARRI Orbiter Fresnel accessory), and by redesigning the lenses (as with the innovative DMG Lion), there are some workarounds to minimize the issue.

One technique to minimize the “wrapping” deficit is to partially spot the fixture focus. This increases the illuminated lens area, although you trade off some beam-shaping control because the light collimation declines the further it’s spotted.

An alternate solution to address the reduced beam shaping is to switch to a completely different type of fixture. “Profile” spotlights (roughly the same as legacy ellipsoidals) can be a better choice, particularly when working at distances greater than 12 feet. Shutter cuts from a “profile” fixture hold up over distance, whereas tight Fresnel barndoor cuts lose beam edge cohesion over longer distances. And since every light becomes a point source when far enough away, “wrap” eventually becomes irrelevant at these greater distances.

The advantages of LED light fixtures over legacy incandescent versions are tremendous, yet we’ve also lost something along the way. While current LED Fresnels fill the gap, I haven’t stopped hoping for a revised design that restores some of what was lost in the process without giving up the gains. “Good enough” isn’t a final destination. It’s just the latest point on the rising line of progress.

Bruce Aleksander is a lighting designer accomplished in multi-camera Television Production with distinguished awards in Lighting Design and videography. Adept and well-organized to deliver a multi-disciplined approach, yielding creative solutions to difficult problems.