Taming Contrasts: Lighting and Shadowing in the Field

What needs to be seen must be within the limits of the camera’s contrast range

In my earlier columns we looked at some of the basics of lighting. As a quick recap, light and shadow work together to create the shading (or “chiaroscuro,” as Renaissance artists called it) to reveal dimensional form. Those visual cues enable a flat medium, like television (or a painter’s canvas), to look three-dimensional. There are other visual cues involved, but here we’re concerned with those created by lighting.

Studio and Field

Moving beyond that theoretical groundwork, let’s consider the practical business of lighting for television. For our purposes, we can break down television lighting into two basic categories: studio and field.

Studio lighting is exemplified by the creation of a plausible space within a controlled environment that’s basically a blank slate. Within its ideal confines, power is always ample, hanging positions are plentiful, and the only limits to what you can create are your imagination and the size of your budget.

And then there’s the world of field shoots—barely contained chaos, with a deadline. Field lighting is typified by constraints beyond the control of the photojournalist, including location, time of day and accessibility.

Freelance photojournalist Jerry Hattan has his own ways of controlling contrast.

“It’s not just about adding more light.” he said. Working “with” the location is always better than trying to “muscle” a solution with brute force. But everything you want to be seen in the picture has to be within the limits of the camera’s contrast range. This is where lighting skills and ingenuity come into play.

Controlling brightness and reducing contrast is fundamental to field lighting. Midday sunlight can reach 10,000 footcandle or more—that’s very bright. You can’t just match those intensities on the talent, because anything more than 2,500 fc will cause people to squint, which is never a good look.

So how do you reduce the contrast between the background and the talent? To an extent, you add “some” light on the talent, but you must also reduce the brightness of the background. Hattan offers an example.

“Take advantage of the natural shade to get the talent out of the direct sunlight,” he said. “Once you’ve softened or eliminated the direct sun, you can add your own lights from a more flattering angle. Making sure the reporters look good is always an important part of the job.”

When existing shade isn’t available, you may need to make your own. Frame-mounted diffusion can create shade and soft fill light, instead of harsh shadows from the direct sunlight. But that requires additional gear.

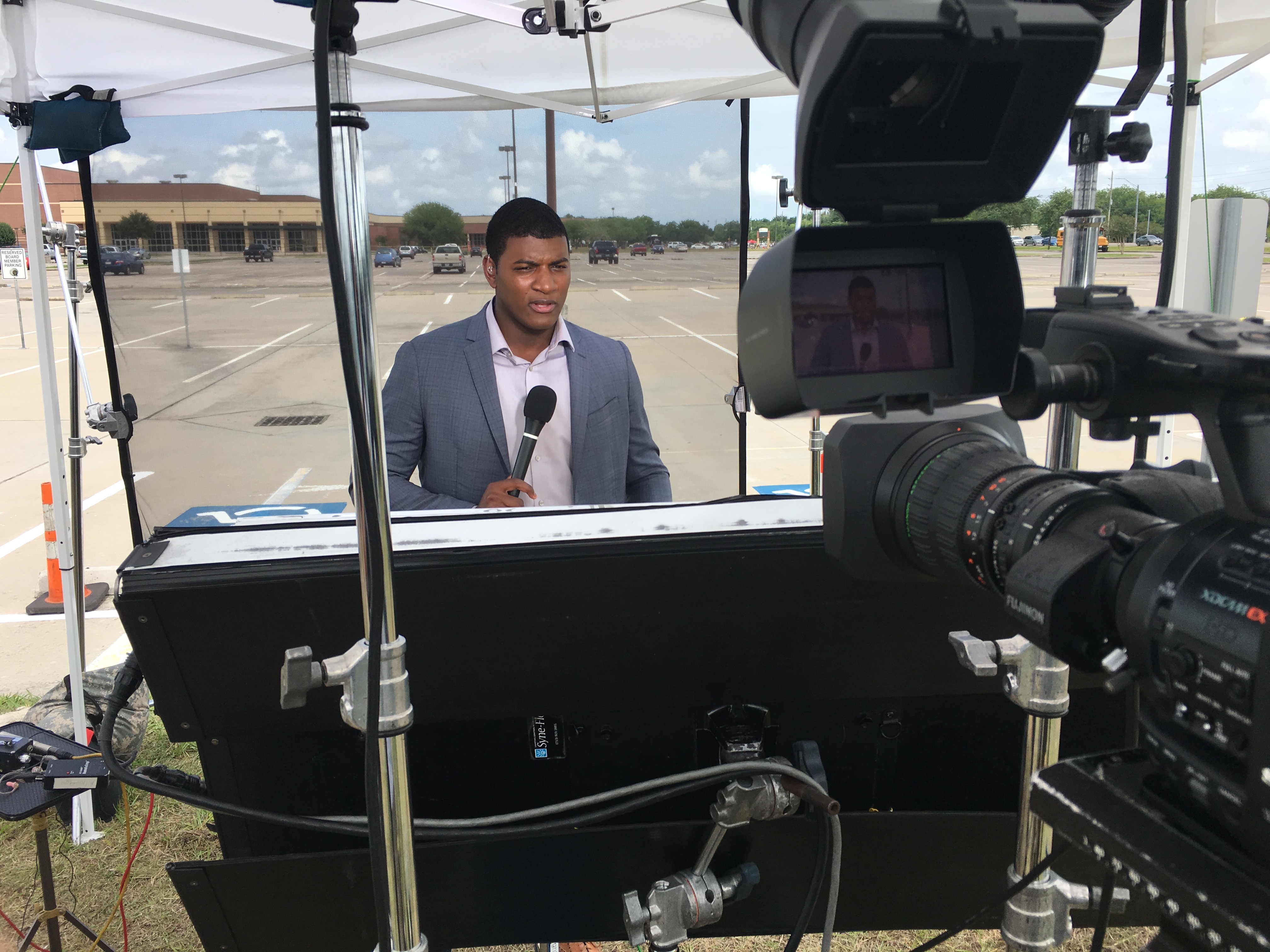

“How we light the talent is often determined by what we can bring to the location” according to cameraman Roger Brooks, of Brooks Video Production & Lighting in Houston. Brooks and Hattan often work together when projects require additional support equipment or a second photographer.

To transport that additional equipment, Brooks notes that “If it doesn’t have wheels, you’re in a world of hurt.” This is why his gear always travels on carts. “There’s almost always a ramp, so rolling carts is an easy way to have the equipment right where it’s needed. You never want to have to go back to the van for something forgotten.”

Even with carts, the equipment still needs to be compact. Several companies make breakdown frames for mounting textiles that can modify or completely block the light. Stands and shot bags are also essential grip equipment to safely support them.

For Example…

A 6X6 silk diffusion does a great job softening the sunlight, but it’s wise to remember that it can become an unruly sail on a windy day. In addition to solid stands and shot bags, it also takes more people to safely handle the gear in such conditions, (Fig. 1).

Another effective way to control bright backgrounds is to add a special double-net screen behind the talent, according to Brooks, (Fig. 2). This technique reduces the background brightness by a full stop from the camera’s perspective, yet it’s transparent to the camera when shot at a wide aperture. It often takes a combination of techniques and equipment to yield the desired look.

“It’s not just the setup. When things change—and they always do outdoors—you have to respond quickly,” said Hattan.

Evening shots present contrast problems of a different kind. Nighttime calls for creating layers of separation in the darkness to keep the image from looking flat. This is where backlights are essential to ensure talent doesn’t disappear into a dark background, (Fig. 3.)

Today, LED lights justifiably dominate the field. The best of them have excellent output and nearly perfect color rendering. They can be dimmed to match changing intensities without color shift, and many are bicolor (if not full color) to match ambient-correlated color temperature.

Although fluorescent, HMI and even incandescent are still used (and useful), no previous light source has the range of flexibility found with LED lights today. And while I may miss the direct simplicity of making light by heating a tungsten coil, I don’t miss the low efficiency and waste heat of incandescent.

Those older light sources will eventually fade into the sunset, replaced by LEDs. As it was with gas lights and kerosene lanterns before them, they’ll soon become quaint relics—more appropriate for nostalgic occasions than lighting sets.

We’re already used to it.

Bruce Aleksander invites comments from those interested in lighting at TVLightingguy@hotmail.com.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.

Bruce Aleksander is a lighting designer accomplished in multi-camera Television Production with distinguished awards in Lighting Design and videography. Adept and well-organized to deliver a multi-disciplined approach, yielding creative solutions to difficult problems.