Celebrating 25 Years: A Focus on Editing

Sound the trumpets. The words you are reading herald the 25th anniversary of this "Focus on Editing" column that began in June, 1985. But I have one question for you: How come none of you look any older?

The medium that we editors command has evolved from sprocket-driven celluloid to digital data files, but the faces of editors I interact with are just as eager, intelligent and involved as they were when this column burst forth with the declaration: "An editor is a creative artist who takes unconnected, diverse ideas and, through the use of context, contrast and rhythm, brings meaning out of confusion."

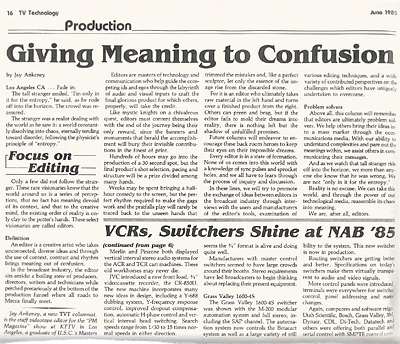

That's why my first entry was titled "Giving Meaning to Confusion," and over the past quarter century it has been my goal to conduct this column's excursions along a triangle of themes: keeping editors abreast of new technology; celebrating the accomplishments of the most talented individuals in our pack; and constructing a cohesive set of principles that editors can use to guide their unique contribution to audio/visual communication.

The author’s first column, appearing in the June 1985 issue of TV Technology. That last point has been a passion of mine, under the proposition that editing is as distinct an art form as music composition or dance choreography. A summation of my decades-long exposition of three great aesthetic tools of the editing trade, context, contrast and rhythm, can be found in my column in the Aug. 20, 2008 issue, titled "The Art of Editing Revisited."

But, of course, it is not always the person operating the editing workstation who is responsible for all of the artistry in an edited scene. While most editors take justifiable pride in being key links in the production chain, the shot selection of a sequence or its juxtaposition of images may, in some cases, come from outside the edit bay.

As an admittedly whimsical conceit, before the end of the last millennium, I nominated as the Greatest Edit of the 20th Century the "bone-to-spaceship" cut that concludes the preamble of Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey." I've never been able to pin down who was responsible for its creation, beyond the obvious fact that Kubrick was himself a powerful auteur, and that cut is not stipulated in the text of the original Clark/Kubrick script. But in one awesomely forward-thrusting collision of imagery, man's leap from inventing tools to conquering space slaps itself into the visual awareness of the audience.

Which begs the question, why does visual editing work at all? How can our minds take two disparate images and create a third, distinct concept when they are banged together?

Just watch people's eyes. They focus, pan, focus, blink, and focus again. The suppression of the pans and blinks forces our brains to synthesize an artificial impression of the world around us. In effect, it edits together disconnected visual inputs to form a cohesive whole.

Perhaps that is why most editors have learned that the soundtrack most often drives an edited sequence's communication. Ears, after all, don't blink. They are attuned to a continuous stream of audio perceptions that satisfy our desire to hear without interruption.

You can see this principle illustrated by the film most historians consider the first edited movie, Edwin S. Porter's 1902 "Life of an American Fireman." Instead of the common practice during that era of setting up a camera beside an intriguing activity such as a train arriving at a station and projecting the clip uncut, Porter sequenced nine shots to tell the story of firemen racing to rescue a family from a burning building.

This film is available for viewing on numerous Web sites, but any modern editor seeing it will immediately notice a quirksome oddity. Although the story has a linear thread, Porter does not do a straight cut from one shot to the other. He fades out and fades in. A bridge of fades separates even the sequence of a hand pulling a fire alarm followed by the responding firemen jumping out of their beds.

Yet in the film's opening image, Porter depicts a sleeping fireman with the domestic dream of his wife and child inserted as a vignette over his shoulder. Porter understood simultaneous juxtaposition, but not yet its more powerful sequential exploitation.

That changed only a year later. Porter had moved on to conventional straight cuts in "The Great Train Robbery," which readily conforms to modern editing techniques. But right after the story's finale comes a presage of cuts to come. One of the bandits sporting a soup-strainer mustache, played by Justus D. Barnes, aims his pistol at the camera and empties the six-shooter directly at the audience, even continuing to pull the trigger when the cylinder is empty.

The author works at a CMX340 keyboard in the training room at CMXIOrrox, Santa Clara, Calif. in 1981. There is no narrative logic to this shot since the outlaw gang had been gunned down before the previous fade to black. But the "bone-to-spaceship" impact of this edit thrilled turn-of-the-century audiences and today's editors can benefit from this "nothing's new" phenomenon.

So what has changed in editing over the past quarter century since this column began? Sure, we no longer boot up our DEC PDP-11 computers by feeding them paper punch tapes, but another development dominates my perspective.

I am struck by how ubiquitous editing has become, and the tremendous access all editors and editing wannabees have to vast libraries of media to help them learn and study their art.

As a budding film student, I often set a wake-up alarm to watch classic films at 2 a.m. Today young editors can see almost any archived production at almost any time on either home discs, video delivery services, or over the Internet.

This tsunami of media has permanently changed the way we work, with mass storage sites such as YouTube increasingly providing source material to anyone with a broadband link and Web-based editing becoming a reality. It won't be long before all recorded images will be mere wisps in the international cloud of cyberspace.

But, of course, all that avalanche of information can only lead to overloaded bewilderment if it is not put into some kind of context. For those who prefer knowledge over chaos, we will still be looking to the role of the editor for "Giving Meaning to Confusion."

Jay Ankeney is a freelance editor and post-production consultant based in Los Angeles. Write him at 220 39th St. (upper), Manhattan Beach, Calif. 90266 or atJayAnkeney@mac.com.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.