Listening to Audio on a Laptop

Our story to date… You may recall that I contributed a piece on loudness to TV Technology's e-book "Guide to Audio Loudness," which was "e-published" in February.

As part of that piece, I provided two audio files, taken directly from live broadcast as provided by DirecTV.

I also measured the acoustical parameters of those files, so that we could study and come to understand a bit more about what goes on in broadcast audio and how it relates to loudness.

Naturally, our esteemed editor Tom Butts sent me the e-book to preview and check out. And naturally, I did. Also equally naturally, I checked it out on my laptop computer sitting on my desk (a Macintosh PowerBook G4) in my office. This is because (a) I'm lazy, (b) I spend most of my time in the office, not the studio, and (c) I've resisted having the Internet in the studio—I'm an offline kinda guy when it comes to studio work.

This means that, when I previewed that e-book for Tom it was the first time I listened to the broadcast audio files I supplied to for the e-book on the built-in speakers on my laptop computer—I do not listen to audio in my office at all.

In general the files sounded okay, if a little lacking in bass and punch. What got my attention, though, was the sense that the best-sounding segment was the one that was loudest (by far) and about which I had written in the e-book: "Clearly, the Roche spot is abusive loudness, and is pushing right up toward the overall limits of the playback system. It's this sort of spot that gets us all in trouble."

So get this: the file for which the loudness police are likely to pillory us (in my opinion, anyway) sounds the best of all when played back on a laptop. How can this be? We've got to talk.

MORE MEASUREMENTS

But first, back to the studio, dragging along the laptop. Set it up. Set up my acoustical measurement rig, placing the test mic about where the user of the laptop might situate his or her head (i.e. 15–18 inches from the screen, right in front). Boot everything. Set all the volume controls in the laptop at max. Open the e-book piece. Play back the files. Measure them. Write it all down. Tear it all down. Shut down the acoustical measurement rig. Drag the laptop back to the office and set it back up so I can get my e-mail and write this article. You know the drill, right?

WHAT I FOUND

So, below is a table that shows what I found (Fig. 1). If you recall, there were two primary segments: an NBA basketball game plus commercial break with three commercials and the opening of Obama's State of the Union address, consisting of a network introduction followed by newscaster commentary.

Fig. 1: Studio Leq, Laptop Leq and Difference in dB for each segment and sub-segment of audio. The components of each segment were also measured separately. There's a column showing the Studio Leq, which I measured in January, one showing the Laptop Leq (which I measured yesterday, in the same room with the same system) and a column showing the difference between them.

"Leq" refers to the "power average" of the entire file, expressed equivalent to Sound Pressure Level (SPL), in this case B-weighted.

Now this is actually pretty interesting. First, the laptop is much softer (ca. 9–12 dB), even up close and personal. Second, the difference varies quite a lot (7–14 dB) depending on the program. This will be due to three things, added together: difference in bass response (huge!), difference in room effects (nearfield vs. farfield, as well as directionality—significant) and possible signal processing in the laptop computer. (I think I hear some additional limiting, but it is unrevealed and unknown).

You can see that voice commentary has less difference between laptop and studio, while stuff with music beds (and bass!) has much more difference.

WHAT IT ALL MEANS

There's lot more to puzzle over here. There are issues of dynamic range, maximum and minimum levels, subjective loudness qualities, spectrum, the difference between monitoring audio in the extreme nearfield with a laptop vs. monitoring audio in the far field in a fully developed home theatre and much more.

However, the takeaway is very simple: monitoring with a computer and its built-in speakers (or equivalent small "computer monitor speakers") is simply not appropriate for producing audio program material to be heard over a full-range home theatre system.

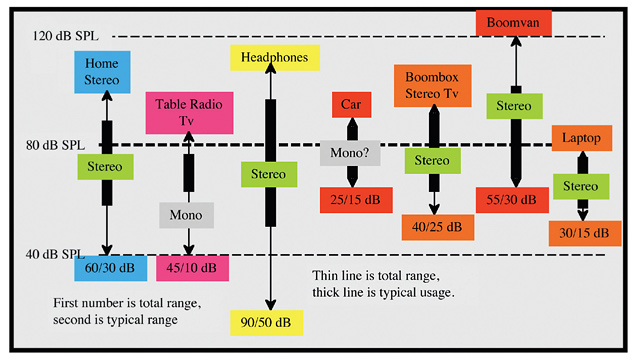

So, in fact, we now have another playback genre here. In my book "Total Recording," I identified and discussed six such genres (living room stereo, mono table radios/TVs, headphones, cars, boombox/stereo TVs, boomvans). Now we have a seventh one: the laptop computer. See Fig. 2, now suitably revised.

Fig. 2: Seven playback genres and their dynamic ranges, adapted from Total Recording, courtesy of the author.

This means it's time to review, once again, the monitoring process you use. To put it simply, you shouldn't mix on the laptop, but you should check your mix on the laptop, as needed.

I wonder how much of the loudness troubles we've gotten into have to do with this—the employees at iZotope (who inspired me to start this series, if you recall) all work on their laptops or equivalent, pretty much all the time. They have no studio playback or equivalent. Further, this is how they watch movies and listen to music for fun. No wonder they thought my studio was loud! No wonder they couldn't hear phantom images, stereo, reverb, or comb filtering.

So once again, I'll reiterate the lesson I learned from this: you need good speakers, placed well in a good room, in order to Listen Critically. And, Critical Listening is, in fact, critical. Amen!

Thanks for listening.

Dave Moulton can't decide where to listen, anymore. It used to be so simple. You can complain to him about anything at his website, www.moultonlabs.com.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.