Measuring Downmix Loudness

JAY YEARY The first time I remember giving any serious consideration to measuring the loudness of two-channel downmixes was at an event that happened in conjunction with the 2012 NAB Show. I had just finished speaking about implementation plans for the CALM Act when an attendee asked if we were planning to measure the downmix loudness of our surround content.

My first thought was that this was a very curious question, which was immediately followed by the realization that I had focused exclusively on surround loudness and hadn’t really considered that the downmix might measure differently.

In fact, surround and downmix loudness may not simply measure differently; the difference could be enough for the two-channel version to be outside the desired loudness delivery specification even though the surround mix meets the loudness target. On top of that, it appears it may actually be more important to pay attention to the downmix rather than the surround version.

THE TEMPTATION

While it’s true that digital television gives us the ability to deliver full fidelity 5.1 mixes to viewers, the fact is that most people still listen in stereo or mono. The temptation here is to use a broad brush and characterize anyone who doesn’t listen in surround as if they are backward or out of touch, but that characterization doesn’t hold up.

Televisions are everywhere, but the same cannot be said for properly configured surround systems. Airports, bars, hotel rooms, offices, restaurants and second and third televisions in homes are rarely connected to a surround system. In addition, content is being listened to on an increasing assortment of portable devices such as smartphones, tablets and laptops that may have only one speaker for playback until earbuds are inserted into the headphone jack. The two-channel listener is all of us.

With so many people listening to downmixed audio in so many places, it is now essential to insure the loudness levels of downmixes are correct. This is enough of a concern that the ATSC, in recommendation A/85:2013, now includes a section covering it.

The document confronts the issue this way: “The loudness of surround programming should be measured in both its surround mix format and in its 2-channel downmix. This is necessary because of the high percentage of consumers experiencing the downmix of surround programming and the possible loudness disparity between the two formats.” The inclusion of this wording in the RP makes it pretty clear that this is an issue worth paying attention to.

So the big question here is: What causes loudness variations between the surround and downmixed versions of content? Downmixing works by summing the left front, right front, center, left surround and right surround channels into a two-channel mix.

In this new mix the center channel gets added to both the left and right channels while the rear surrounds go to their respective sides. The left and right front channels enter into this mashup with no changes, but the center and surround channels (typically) have their level lowered by 3 dB.

The rear surround channels also lose the 1.5 dB of boost they’re given when measured in surround, so they contribute less to the downmix measurement than the other channels. All of this summing and gain reduction means the primary determinant for how closely surround and downmix loudness match is where elements are placed in the surround mix. A/85 states that differences in those loudness measurements are most often caused by, “Content mixed in phase in the three front channels,” but the problem is not quite that easy to diagnose or avoid.

PUTTING IT TO THE TEST

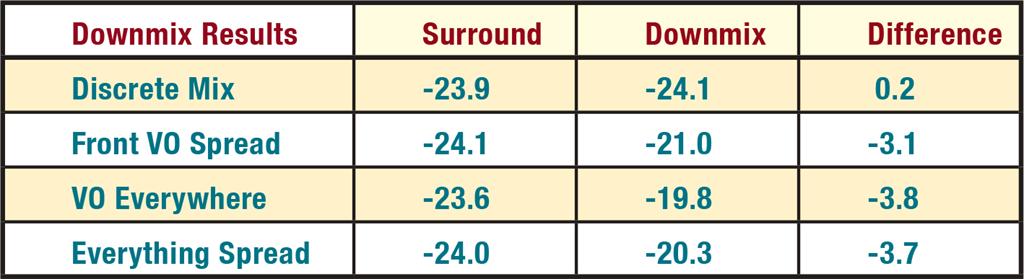

Fig. 1: Downmix test results In order to see exactly how soundfield placement changes loudness measurements, I built a 30-second promo with elements consisting of voiceover, soundbites, sound effects and a music bed. All elements were imported into a digital audio workstation as mono sound files so they could be easily placed in the 5.1 soundfield. An initial stereo mix was created and loudness was measured at –24 LKFS.

Next, four surround mixes were created by moving the elements to different locations in the soundfield. The primary surround mix was essentially fully discrete, with voiceover and soundbites in the center, music in left and right and sound effects in the rear surrounds. The second surround mix spread the voiceover and soundbites across all front channels, followed by a third mix with voiceover and soundbites in all channels. (Note: the LFE channel was not used for any of these mixes).

Finally a very wide, fully spread surround mix was created, with music and sound effects in left, right and surround channels, and speech spread across all channels.

After verifying that each surround mix still sounded reasonably good, loudness measurements were taken using two different BS.1770-3 meters. Then each surround mix was downmixed and loudness measurements of each downmix were taken.

Results can be seen in Fig. 1. The downmix loudness of the discrete version was extremely close to the measurement of the original surround mix, but the other versions were each off by more than 3 dB. Considering that A/85 allows only a 2 dB variance from target, all of the other downmixes would be out of compliance, even though their corresponding surround mixes remain essentially on target.

This experiment is neither exhaustive nor scientific, but it does point out how easy it is for a downmix to stray from the loudness target and how much care mixers need to take with both their mixes and their measurements if they want to deliver audio content that is in compliance with delivery specifications.

After spending some time creating these mixes it became obvious that keeping elements in discrete channels as much as possible and not summing across the three front channels went a long way toward producing content with loudness that matched on both the surround and downmixed versions.

Mixers need to always be conscious of where each element is placed in the soundfield of their surround mix and may find it necessary to adjust the surround mix to provide downmixes with matching loudness levels.

Jay Yeary is an audio engineer working in broadcast television for a large media corporation. He can be contacted via Twitter at TVTechJay.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.