The Golden Age of 3D Movies

The recent phenomenal success of the 3D movie "Avatar" whet the appetites of the movie studios, which are hoping to sell a whole lot of high-priced tickets to 3D movies in the near future.

Television set manufacturers are offering 3D sets, hoping to cash in on the hoped-for 3D wave, and 3D cable channels are in the planning stages or have already launched. Will the 3D movement succeed? It is impossible to say at this point.

The Golden Age of movies was indisputably the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1950s, the movie studios made major efforts to lure people away from their newfangled TV sets and back into the theaters.

Historically, up to this point, the dominant aspect ratio for movies had been 4:3. This was, in fact, the reason that TV adopted the 4:3 aspect ratio: to emulate the movies.

So the studios went further, by developing wide-screen systems such as CinemaScope, Cinerama, and 70mm projection. These formats could enthrall viewers, but at a cost.

Cinerama, for example, used no fewer than three tightly synchronized projectors to project images on a deeply curved, wrap-around screen subtending a whopping 146 degree arc, literally enveloping the viewer with its images. The screen was divided into 7/8-inch horizontal strips, each of which was tilted toward the viewer.

Because the curved screen so involved the viewer's peripheral vision, which is extremely sensitive to any kind of movement, the normal frame rate of 24 per second generated excessive flicker at the peripheries, even in the dim theater environment, so the Cinerama features were shot and run at 30 fps. The features were shot with three synchronized 35mm cameras sharing a single lens. And, in the "nothing new under the sun department," Cinerama features were accompanied by 7-channel sound tracks.

THE FIRST 'GOLDEN AGE'

The brief Golden Age of 3D movies also occurred during the 1950s. Contrary to the myths, very few of these 3D features used the red and green glasses we see in the old photographs; most of them used light polarization, as is being used currently. These were double-system projections, using two 35mm projectors side-by-side. The resolution of 35mm film, plus the bright images thrown by the two projectors, produced bright, clear 3D impressions that were arguably better than can be achieved by today's single digital 3D projectors—but at a cost. The two projectors had to be maintained in synchronization to at least within two frames, or the images were unwatchable.

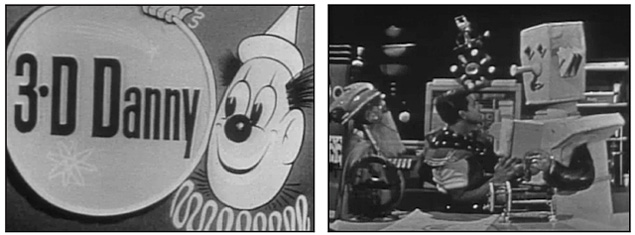

Visit YouTube to view a surviving “3D Danny” episode starring Danny Williams from the 1950s. This was a 16mm kinescope of the original broadcast. It was a locally produced program by WKY-TV NBC affiliate in Oklahoma City, Okla.

The first 3D feature to hit the theaters in 1952 was "Man in the Dark," which beat the famous "House of Wax" by about two weeks. It began the trend that continued for most of the Golden Age of 3D—appearing to poke objects like surgical scalpels, lighted cigars, and rubber spiders at the viewer. 3D cowboys shot sixguns and spit tobacco at the hapless viewer. In short, 3D was a gimmick.

By the 1953 holiday season, the studios had toned down the gimmickry and produced 3D versions of some of their "A" features, including the musical "Kiss Me Kate" and Alfred Hitchcock's "Dial M for Murder."

But the moment had passed. While "Kiss Me Kate" was actually released in both 3D and 2D versions, "Dial M for Murder" was never released in 3D. And the Golden Age of 3D had only lasted a little more than a year.

3D OF TODAY

While very good 3D was shown in the 1950s, today's advanced projectors and displays make better 3D feasible in theaters and at home. Many approaches to 3D representation are used, most of them involving polarized light, using either linear or circular polarization.

Some involve fast polarization switching at the source and in the viewer's glasses, using liquid crystal. In the theater, three-chip DLP projectors are frequently used, illuminated by either Xenon lamps or lasers. For home television sets, CCFL or LED-illuminated LCDs are a common approach for 3D.

Does the television-watching public want 3D? This remains to be seen. 3DTV is very new, and while manufacturers are making 3D sets, little 3D program material is currently available to watch on them. This will change, as there will be 3D cable channels available. One of these, ESPN 3D, was launched last June.

3D might hold promise for sports enthusiasts. It will, of course, require a whole different approach to shooting sports, in order to take advantage of three dimensions. In football, for example, there might be a lot of shooting from the end zones, so the viewer can be treated to football players running directly at them. Sports was a big driver for HDTV, and it might do the same for 3D. There is also the potential for endless 3D CGI.

Back in the real world, home viewers who recently shelled out for a new HDTV set are being asked to buy yet another expensive TV set, and this might be a difficult sell.

It is interesting to note that an online survey conducted this past summer in Japan, a technophile's paradise, revealed some interesting information about the prospects for selling 3DTV there. Nearly 9,000 people responded, and the bottom line is that almost 70 percent of respondents said that they had no plans to buy a 3DTV set for their homes.

The key reasons for the disinterest included, in descending order, wearing special glasses is a hassle; the prices are too high; and there is not enough 3D content available.

Likewise, a recent Zagat survey in the United States indicated that 65 percent of respondents had no plans for 3D in their homes.

Will 3D TV emulate 3D movies in their Golden Age, proving to be a flash-in-the-pan novelty? Or will it come to occupy a significant position in home TV viewing? Only time will tell.

Randy Hoffner is a veteran of the big three TV networks. He can be reached through TV Technology.

Get the TV Tech Newsletter

The professional video industry's #1 source for news, trends and product and tech information. Sign up below.